“Good artists copy, great artists steal” - Pablo Picasso

"Great artists steal” is an intriguing quote, but is it really true? What kind of theft are we actually talking about? Were Picasso, Dali, and Matisse international art thieves? Probably not, but it would make a great movie. How you interpret this quote is important because it reveals everything about your artistic process, and who you are as an artist. In considering what it really means we have three categories to think about, Theft, Copying, and Inspiration.

Theft is either going into a museum or a home and taking a painting off the wall, or it is presenting someone else’s work as your own, such as using another photographer’s images on your website. We can all agree this type of stealing is wrong and it is a safe bet this is not what Picasso meant.

Copying is looking at someone else’s work and then photographing similar subjects in a similar way, it is mimicry. It is taking elements from another artist without transforming them. Another photographer is dressing babies up like flowers or putting clothes on dogs and gets great results so maybe I should do it too. Please don’t.

Inspiration” or “getting inspired” by another artist are very broad terms. You could admire their drive, methods, tools, their choice of color or technique. Drawing inspiration from another artist means to take elements of what they do or how they do it, transform them, and apply them to your work. This is what “Take it and make it your own” means. The confusion between copying or drawing inspiration from is where we have issues as to what the quote means.

The key to improving your own work through inspiration is transformation. The elements you draw from another artist should be so changed that even the original artist would not recognize them. If you stole a car and had it repainted, the rightful owner could still recognize their car. But if you took parts from ten different cars, repainted, reshaped, and assembled them together, you would have an entirely new vehicle. If someone can recognize the source of your inspiration, you haven’t transformed it enough.

Whether someone copies, or transforms is dependent on what they think about originality. If you don’t believe originality exists, then you believe all creation is an act of copying. “Nothing’s original.” “It’s all been done,” these beliefs often come into conversations between photographers. The idea there is “nothing new under the sun” is not a new one. That quote is from Ecclesiastes 1:9. This idea has been with us a long time, but we have a longer history of original thinking. Just because it is hard for us to imagine new and original ideas doesn’t mean they stop happening, the radio, the Tesla coil, the theory of gravity, the number zero, and photography are all original ideas. The real trouble with thinking there is nothing new is it keeps you from creating something new, because you don’t believe it is possible.

In 1903 Albert A. Michelson wrote, “The more important fundamental laws and facts of physical science have all been discovered…” This was two years before Einstein published his first paper on relativity. Michelson was not an idiot, he won the Nobel Prize for physics, but even he thought it had all been done.

Charles Holland Duell was Commissioner of Patents. He supposedly resigned from his position in 1899 because “Everything that could be invented has been invented.” The story is not true, but we accept it as fact, and we laugh that someone could be so foolish. This was before the airplane, the television, the microwave, it would be silly to think there were no new ideas back in 1899 because we all know we didn’t reach this point until 1992 and the invention of the internet right?

Dick Fosbury was a student athlete who revolutionized the high jump. The high jump as a sporting event had been around for over a hundred years when in 1963 a sixteen year old Fosbury started trying a different way. He started jumping over the bar backwards. He was laughed at, and made fun of, and he also won an Olympic gold medal in 1968. You know why a sixteen year old kid was able to revolutionize a long established sport, he wasn't "smart" enough to know there is no such thing as an original thought.

As art, science, and technology progress, there may be fewer big discoveries, but that does not mean original ideas don’t exist. In the creative fields originality is much easier to come by than in other fields. Appliance makers will never combine a toaster with a washing machine, but an artist can. We have so much more room to be creative and original, it is almost criminal when we are not.

Statements like “Nothing’s original” are a self-given license to copy. You don’t have to feel bad about taking somebody’s else creative work because it’s all been done. One is free to copy as they please, but there is a fundamental problem most people who copy make. When anyone copies, they fail to understand the original thinking that went into the finished piece. Without knowing why an artist made certain decisions, the result is bound to be a very poor copy.

In the days of vaudeville there was a fascination with magic from the Orient. This started with the Chinese magician Ching Ling Foo. Foo’s act was copied by an American magician who called himself Chung Ling Soo, but was really William Ellsworth Robinson. The popularity of the two men led to even more copycats and a trend of painting illusions and magic tricks with Chinese lettering. The story goes that a stage magician after building his own illusion copied some lettering from a street sign he saw in a book on China. There was never any issue with the illusion until he performed in front of a Chinese audience. When he brought out the illusion the auditorium was filled with laughter. He got through the trick the best he could, but he was confused. After the show an audience member came up to the magician.

"Do you know why we laughed?” he asked.

"No,” said the magician.

"Do you know what the words on your box mean?”

"No, I do not.”

"It translates into English as,

Don’t Urinate in the Alley.”

There are valid reasons to copy, and this may add to the confusion. Go to major museums and you will routinely see students with their big drawing pads sketching sculptures or paintings. It is valuable way to learn composition, anatomy, uses of light, and how art is made. For photographers trying to replicate someone else’s work is a great way to learn how others would

set their lights and pose their models. These are learning exercises, they are useful and enlightening but they should remain buried in an archive and not displayed.

So what did Picasso mean by the quote? It is impossible to say—Picasso never said it. It was Steve Jobs who said Picasso said it, but the notion goes back much earlier. W. H. Davenport Adams wrote in 1892 an article on the poet Tennyson. In it he writes, “… great poets imitate and improve, whereas small ones steal and spoil.”

You can read more about it and other versions of this saying

here.

The fact that people think Picasso said it highlights the problem. Steve Jobs copied it from somewhere, and now we think there is a relationship between great artists and stealing. What Picasso did say was, “Where there is anything to steal, I steal.” He was speaking about the natural growth of an artist learning from other artists. Picasso drew techniques and ideas from many artists, combined them and transformed them into something new, something unique. This is vastly different from copying a finished work, or stealing someone’s intellectual property. To be fair, Jobs did take the original quote and transform it into something new, something Picasso would not recognize as his own. So he did “Steal” in the right way.

The way to properly “Steal” from another artist is to understand the way they thought. Look at their work, read about their lives, and seek out why they created what they did. What problems where they trying to solve, and ask how you would solve those problems. Apply their thoughts and techniques to your own work and your own subject matter. “Steal” in this way, and you will not be copying, you will be creating something new. This is how to draw inspiration from other’s work without copying.

I’ve actually “stolen” from Picasso, but no one would look at my work and recognize what I stole, because I transformed it. In creating his sculpture “Guitar,” Picasso looked at the individual elements of a guitar. The curved shape of the sides, the neck, the strings, the sound hole. He then created pieces representing those single elements. An open tube looks like the sound hole, a flat piece curved on one side suggests the curve of the body, a piece on top represents the sound board, wire stands in for the strings. He took the separate elements, looked for a substitute, and then put it back together. All the elements of a guitar are there, but assembled into something new. This idea led me to a new way of thinking about photography. I started thinking about what was the smallest element I could show in a photograph that would still represent a larger idea. Looking for small details that tell a larger story is what I stole from Picasso, but no one ever knew until now.

This is the type of stealing Picasso meant. Take elements from other artists, transform them (make them your own) in such a way you have removed all evidence from the scene of the crime. Copying someone's work is the least original idea you can have, followed closely by the thought there are no original ideas. There are, but you have to invent them. You won't invent them, unless you look for them, and you don't look for something you don't think is there. That is the real danger in misinterpreting “great artists steal,” and thinking “nothing’s original,” because you can be original, your work can be original if you allow it to be.

All images ©Thann Clark unless otherwise noted.

“Good artists copy, great artists steal” - Pablo Picasso

"Great artists steal” is an intriguing quote, but is it really true? What kind of theft are we actually talking about? Were Picasso, Dali, and Matisse international art thieves? Probably not, but it would make a great movie. How you interpret this quote is important because it reveals everything about your artistic process, and who you are as an artist. In considering what it really means we have three categories to think about, Theft, Copying, and Inspiration.

Theft is either going into a museum or a home and taking a painting off the wall, or it is presenting someone else’s work as your own, such as using another photographer’s images on your website. We can all agree this type of stealing is wrong and it is a safe bet this is not what Picasso meant.

Copying is looking at someone else’s work and then photographing similar subjects in a similar way, it is mimicry. It is taking elements from another artist without transforming them. Another photographer is dressing babies up like flowers or putting clothes on dogs and gets great results so maybe I should do it too. Please don’t.

“Good artists copy, great artists steal” - Pablo Picasso

"Great artists steal” is an intriguing quote, but is it really true? What kind of theft are we actually talking about? Were Picasso, Dali, and Matisse international art thieves? Probably not, but it would make a great movie. How you interpret this quote is important because it reveals everything about your artistic process, and who you are as an artist. In considering what it really means we have three categories to think about, Theft, Copying, and Inspiration.

Theft is either going into a museum or a home and taking a painting off the wall, or it is presenting someone else’s work as your own, such as using another photographer’s images on your website. We can all agree this type of stealing is wrong and it is a safe bet this is not what Picasso meant.

Copying is looking at someone else’s work and then photographing similar subjects in a similar way, it is mimicry. It is taking elements from another artist without transforming them. Another photographer is dressing babies up like flowers or putting clothes on dogs and gets great results so maybe I should do it too. Please don’t.

Inspiration” or “getting inspired” by another artist are very broad terms. You could admire their drive, methods, tools, their choice of color or technique. Drawing inspiration from another artist means to take elements of what they do or how they do it, transform them, and apply them to your work. This is what “Take it and make it your own” means. The confusion between copying or drawing inspiration from is where we have issues as to what the quote means.

The key to improving your own work through inspiration is transformation. The elements you draw from another artist should be so changed that even the original artist would not recognize them. If you stole a car and had it repainted, the rightful owner could still recognize their car. But if you took parts from ten different cars, repainted, reshaped, and assembled them together, you would have an entirely new vehicle. If someone can recognize the source of your inspiration, you haven’t transformed it enough.

Whether someone copies, or transforms is dependent on what they think about originality. If you don’t believe originality exists, then you believe all creation is an act of copying. “Nothing’s original.” “It’s all been done,” these beliefs often come into conversations between photographers. The idea there is “nothing new under the sun” is not a new one. That quote is from Ecclesiastes 1:9. This idea has been with us a long time, but we have a longer history of original thinking. Just because it is hard for us to imagine new and original ideas doesn’t mean they stop happening, the radio, the Tesla coil, the theory of gravity, the number zero, and photography are all original ideas. The real trouble with thinking there is nothing new is it keeps you from creating something new, because you don’t believe it is possible.

Inspiration” or “getting inspired” by another artist are very broad terms. You could admire their drive, methods, tools, their choice of color or technique. Drawing inspiration from another artist means to take elements of what they do or how they do it, transform them, and apply them to your work. This is what “Take it and make it your own” means. The confusion between copying or drawing inspiration from is where we have issues as to what the quote means.

The key to improving your own work through inspiration is transformation. The elements you draw from another artist should be so changed that even the original artist would not recognize them. If you stole a car and had it repainted, the rightful owner could still recognize their car. But if you took parts from ten different cars, repainted, reshaped, and assembled them together, you would have an entirely new vehicle. If someone can recognize the source of your inspiration, you haven’t transformed it enough.

Whether someone copies, or transforms is dependent on what they think about originality. If you don’t believe originality exists, then you believe all creation is an act of copying. “Nothing’s original.” “It’s all been done,” these beliefs often come into conversations between photographers. The idea there is “nothing new under the sun” is not a new one. That quote is from Ecclesiastes 1:9. This idea has been with us a long time, but we have a longer history of original thinking. Just because it is hard for us to imagine new and original ideas doesn’t mean they stop happening, the radio, the Tesla coil, the theory of gravity, the number zero, and photography are all original ideas. The real trouble with thinking there is nothing new is it keeps you from creating something new, because you don’t believe it is possible.

In 1903 Albert A. Michelson wrote, “The more important fundamental laws and facts of physical science have all been discovered…” This was two years before Einstein published his first paper on relativity. Michelson was not an idiot, he won the Nobel Prize for physics, but even he thought it had all been done.

Charles Holland Duell was Commissioner of Patents. He supposedly resigned from his position in 1899 because “Everything that could be invented has been invented.” The story is not true, but we accept it as fact, and we laugh that someone could be so foolish. This was before the airplane, the television, the microwave, it would be silly to think there were no new ideas back in 1899 because we all know we didn’t reach this point until 1992 and the invention of the internet right?

In 1903 Albert A. Michelson wrote, “The more important fundamental laws and facts of physical science have all been discovered…” This was two years before Einstein published his first paper on relativity. Michelson was not an idiot, he won the Nobel Prize for physics, but even he thought it had all been done.

Charles Holland Duell was Commissioner of Patents. He supposedly resigned from his position in 1899 because “Everything that could be invented has been invented.” The story is not true, but we accept it as fact, and we laugh that someone could be so foolish. This was before the airplane, the television, the microwave, it would be silly to think there were no new ideas back in 1899 because we all know we didn’t reach this point until 1992 and the invention of the internet right?

Dick Fosbury was a student athlete who revolutionized the high jump. The high jump as a sporting event had been around for over a hundred years when in 1963 a sixteen year old Fosbury started trying a different way. He started jumping over the bar backwards. He was laughed at, and made fun of, and he also won an Olympic gold medal in 1968. You know why a sixteen year old kid was able to revolutionize a long established sport, he wasn't "smart" enough to know there is no such thing as an original thought.

As art, science, and technology progress, there may be fewer big discoveries, but that does not mean original ideas don’t exist. In the creative fields originality is much easier to come by than in other fields. Appliance makers will never combine a toaster with a washing machine, but an artist can. We have so much more room to be creative and original, it is almost criminal when we are not.

Dick Fosbury was a student athlete who revolutionized the high jump. The high jump as a sporting event had been around for over a hundred years when in 1963 a sixteen year old Fosbury started trying a different way. He started jumping over the bar backwards. He was laughed at, and made fun of, and he also won an Olympic gold medal in 1968. You know why a sixteen year old kid was able to revolutionize a long established sport, he wasn't "smart" enough to know there is no such thing as an original thought.

As art, science, and technology progress, there may be fewer big discoveries, but that does not mean original ideas don’t exist. In the creative fields originality is much easier to come by than in other fields. Appliance makers will never combine a toaster with a washing machine, but an artist can. We have so much more room to be creative and original, it is almost criminal when we are not.

Statements like “Nothing’s original” are a self-given license to copy. You don’t have to feel bad about taking somebody’s else creative work because it’s all been done. One is free to copy as they please, but there is a fundamental problem most people who copy make. When anyone copies, they fail to understand the original thinking that went into the finished piece. Without knowing why an artist made certain decisions, the result is bound to be a very poor copy.

Statements like “Nothing’s original” are a self-given license to copy. You don’t have to feel bad about taking somebody’s else creative work because it’s all been done. One is free to copy as they please, but there is a fundamental problem most people who copy make. When anyone copies, they fail to understand the original thinking that went into the finished piece. Without knowing why an artist made certain decisions, the result is bound to be a very poor copy.

In the days of vaudeville there was a fascination with magic from the Orient. This started with the Chinese magician Ching Ling Foo. Foo’s act was copied by an American magician who called himself Chung Ling Soo, but was really William Ellsworth Robinson. The popularity of the two men led to even more copycats and a trend of painting illusions and magic tricks with Chinese lettering. The story goes that a stage magician after building his own illusion copied some lettering from a street sign he saw in a book on China. There was never any issue with the illusion until he performed in front of a Chinese audience. When he brought out the illusion the auditorium was filled with laughter. He got through the trick the best he could, but he was confused. After the show an audience member came up to the magician.

"Do you know why we laughed?” he asked.

"No,” said the magician.

"Do you know what the words on your box mean?”

"No, I do not.”

"It translates into English as, Don’t Urinate in the Alley.”

In the days of vaudeville there was a fascination with magic from the Orient. This started with the Chinese magician Ching Ling Foo. Foo’s act was copied by an American magician who called himself Chung Ling Soo, but was really William Ellsworth Robinson. The popularity of the two men led to even more copycats and a trend of painting illusions and magic tricks with Chinese lettering. The story goes that a stage magician after building his own illusion copied some lettering from a street sign he saw in a book on China. There was never any issue with the illusion until he performed in front of a Chinese audience. When he brought out the illusion the auditorium was filled with laughter. He got through the trick the best he could, but he was confused. After the show an audience member came up to the magician.

"Do you know why we laughed?” he asked.

"No,” said the magician.

"Do you know what the words on your box mean?”

"No, I do not.”

"It translates into English as, Don’t Urinate in the Alley.”

There are valid reasons to copy, and this may add to the confusion. Go to major museums and you will routinely see students with their big drawing pads sketching sculptures or paintings. It is valuable way to learn composition, anatomy, uses of light, and how art is made. For photographers trying to replicate someone else’s work is a great way to learn how others would set their lights and pose their models. These are learning exercises, they are useful and enlightening but they should remain buried in an archive and not displayed.

So what did Picasso mean by the quote? It is impossible to say—Picasso never said it. It was Steve Jobs who said Picasso said it, but the notion goes back much earlier. W. H. Davenport Adams wrote in 1892 an article on the poet Tennyson. In it he writes, “… great poets imitate and improve, whereas small ones steal and spoil.”

You can read more about it and other versions of this saying here.

The fact that people think Picasso said it highlights the problem. Steve Jobs copied it from somewhere, and now we think there is a relationship between great artists and stealing. What Picasso did say was, “Where there is anything to steal, I steal.” He was speaking about the natural growth of an artist learning from other artists. Picasso drew techniques and ideas from many artists, combined them and transformed them into something new, something unique. This is vastly different from copying a finished work, or stealing someone’s intellectual property. To be fair, Jobs did take the original quote and transform it into something new, something Picasso would not recognize as his own. So he did “Steal” in the right way.

The way to properly “Steal” from another artist is to understand the way they thought. Look at their work, read about their lives, and seek out why they created what they did. What problems where they trying to solve, and ask how you would solve those problems. Apply their thoughts and techniques to your own work and your own subject matter. “Steal” in this way, and you will not be copying, you will be creating something new. This is how to draw inspiration from other’s work without copying.

There are valid reasons to copy, and this may add to the confusion. Go to major museums and you will routinely see students with their big drawing pads sketching sculptures or paintings. It is valuable way to learn composition, anatomy, uses of light, and how art is made. For photographers trying to replicate someone else’s work is a great way to learn how others would set their lights and pose their models. These are learning exercises, they are useful and enlightening but they should remain buried in an archive and not displayed.

So what did Picasso mean by the quote? It is impossible to say—Picasso never said it. It was Steve Jobs who said Picasso said it, but the notion goes back much earlier. W. H. Davenport Adams wrote in 1892 an article on the poet Tennyson. In it he writes, “… great poets imitate and improve, whereas small ones steal and spoil.”

You can read more about it and other versions of this saying here.

The fact that people think Picasso said it highlights the problem. Steve Jobs copied it from somewhere, and now we think there is a relationship between great artists and stealing. What Picasso did say was, “Where there is anything to steal, I steal.” He was speaking about the natural growth of an artist learning from other artists. Picasso drew techniques and ideas from many artists, combined them and transformed them into something new, something unique. This is vastly different from copying a finished work, or stealing someone’s intellectual property. To be fair, Jobs did take the original quote and transform it into something new, something Picasso would not recognize as his own. So he did “Steal” in the right way.

The way to properly “Steal” from another artist is to understand the way they thought. Look at their work, read about their lives, and seek out why they created what they did. What problems where they trying to solve, and ask how you would solve those problems. Apply their thoughts and techniques to your own work and your own subject matter. “Steal” in this way, and you will not be copying, you will be creating something new. This is how to draw inspiration from other’s work without copying.

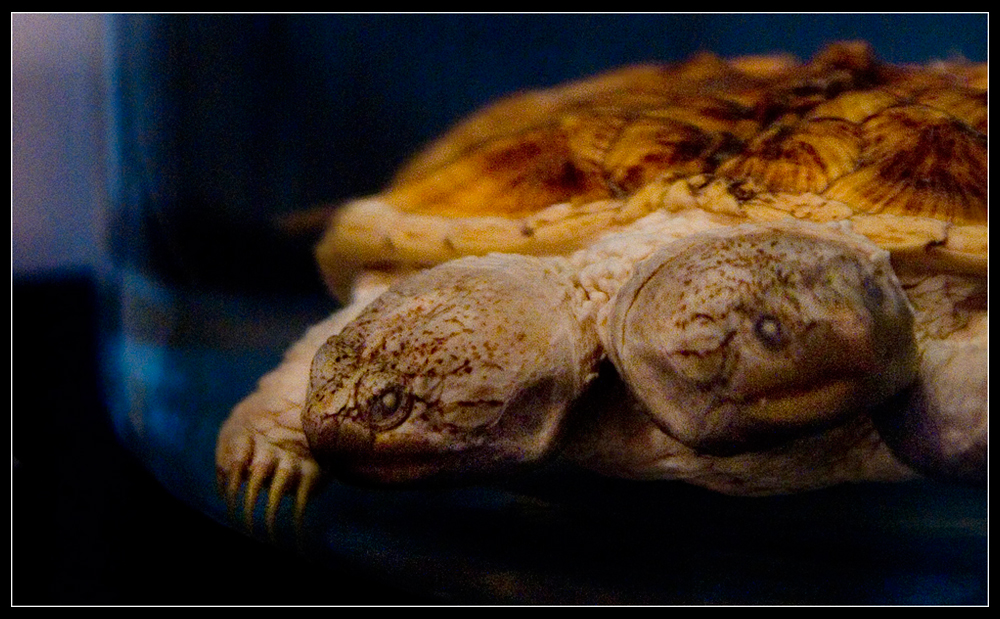

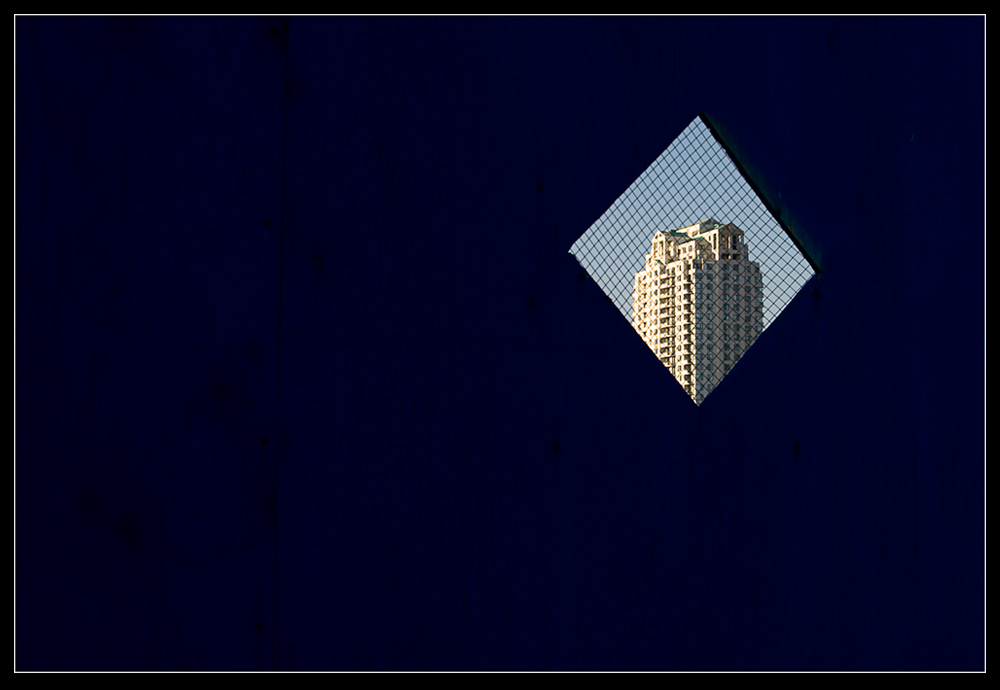

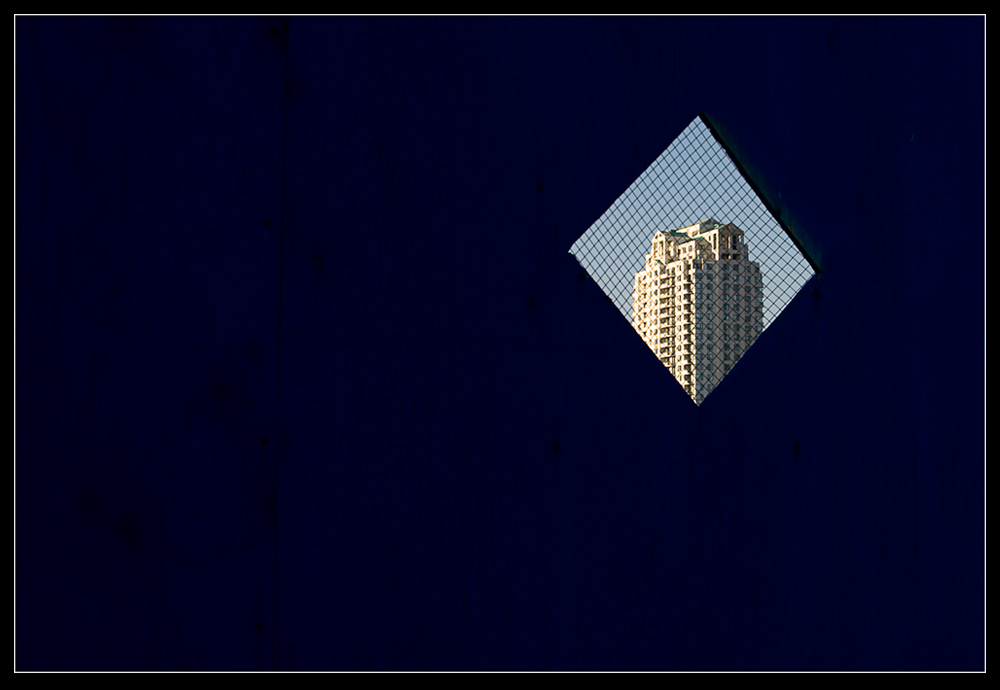

I’ve actually “stolen” from Picasso, but no one would look at my work and recognize what I stole, because I transformed it. In creating his sculpture “Guitar,” Picasso looked at the individual elements of a guitar. The curved shape of the sides, the neck, the strings, the sound hole. He then created pieces representing those single elements. An open tube looks like the sound hole, a flat piece curved on one side suggests the curve of the body, a piece on top represents the sound board, wire stands in for the strings. He took the separate elements, looked for a substitute, and then put it back together. All the elements of a guitar are there, but assembled into something new. This idea led me to a new way of thinking about photography. I started thinking about what was the smallest element I could show in a photograph that would still represent a larger idea. Looking for small details that tell a larger story is what I stole from Picasso, but no one ever knew until now.

I’ve actually “stolen” from Picasso, but no one would look at my work and recognize what I stole, because I transformed it. In creating his sculpture “Guitar,” Picasso looked at the individual elements of a guitar. The curved shape of the sides, the neck, the strings, the sound hole. He then created pieces representing those single elements. An open tube looks like the sound hole, a flat piece curved on one side suggests the curve of the body, a piece on top represents the sound board, wire stands in for the strings. He took the separate elements, looked for a substitute, and then put it back together. All the elements of a guitar are there, but assembled into something new. This idea led me to a new way of thinking about photography. I started thinking about what was the smallest element I could show in a photograph that would still represent a larger idea. Looking for small details that tell a larger story is what I stole from Picasso, but no one ever knew until now.

This is the type of stealing Picasso meant. Take elements from other artists, transform them (make them your own) in such a way you have removed all evidence from the scene of the crime. Copying someone's work is the least original idea you can have, followed closely by the thought there are no original ideas. There are, but you have to invent them. You won't invent them, unless you look for them, and you don't look for something you don't think is there. That is the real danger in misinterpreting “great artists steal,” and thinking “nothing’s original,” because you can be original, your work can be original if you allow it to be.

All images ©Thann Clark unless otherwise noted.

This is the type of stealing Picasso meant. Take elements from other artists, transform them (make them your own) in such a way you have removed all evidence from the scene of the crime. Copying someone's work is the least original idea you can have, followed closely by the thought there are no original ideas. There are, but you have to invent them. You won't invent them, unless you look for them, and you don't look for something you don't think is there. That is the real danger in misinterpreting “great artists steal,” and thinking “nothing’s original,” because you can be original, your work can be original if you allow it to be.

All images ©Thann Clark unless otherwise noted.