D

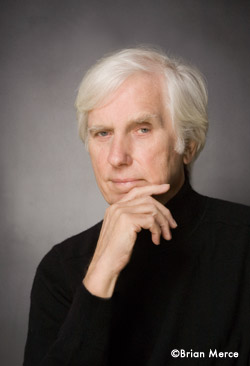

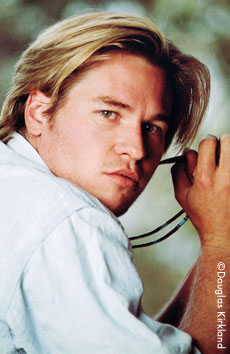

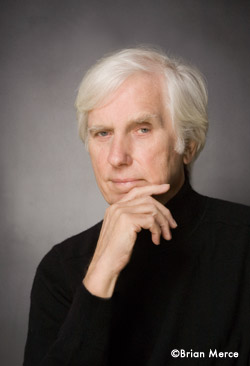

Douglas Kirkland is one of the most respected and celebrated photographers of the last fifty years. His career and the people he has photographed are legendary. At age twenty-four, Kirkland was hired as a staff photographer for Look magazine and became famous for his 1961 photos of Marilyn Monroe. He continues to accomplish memorable images today that deal with the entertainment industry and he also shoots for prestigious magazines such as Vanity Fair. This interview was conducted at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences where his photographs were on display.

Q: In simple terms could you explain your beginnings as a photographer? What age were you when you started taking pictures? What was your first camera like? When did you start working in the darkroom?

A: Ok. I started working in photography at a very young age, I lived in a very small town up in Canada, 7000 people, called Fort Erie, right opposite Buffalo, New York, and I was a kid with dreams. And I've been able to live those dreams very much, more even than I would have ever imagined. When I was ten I took my first picture with a box brownie of my family out in front of the house on a Christmas day, a really cold Christmas day, Click! One frame that's indelibly locked in my mind. The affect of that, two years later, I was starting to work with the speed graphic, a big 4x5 camera with sheet films. I was about twelve years old when I started, but I really got working more when I was about fourteen, but I took my first picture at ten, a single image. At fourteen, I was working with a local photo studio after school and on Saturdays and they had me doing all sorts of things; photographing babies, photographing organization's meetings, photographing occasionally for the small town newspaper, The Times Review, that was a big deal, a weekly newspaper.

Q: Let me ask you, what do you think makes photography special? I mean what makes it different from, say, the other arts, such as painting or sculpture or literature?

A: Well Tony, I'm in love with all the arts. There's no question of that, and photography for me is the most embracing because I have made films at one time, briefly. And the problem with that is you can't just pick up the camera any day and go out and shoot, which you can as a still photographer. And that's why I have a special love for still photography. You don't have to cut a deal. You don't have to get a group together to shoot. It's becoming simpler today as we see right here where I sit. You can do much. Yes, but my great love is still photography because it's very hands on. As I did in the early days, you can go into the darkroom, develop your film, make your prints, blow them up, explore and discover, find errors, make mistakes and then redo it and keep learning. And that's what I do today with digital cameras, I work with digital as well as film, but when I work with digital I'm on to the computer. That is so igniting! It just ignites me. It sets me up. It's truly exciting!

Q: Do you think it's possible to describe the ingredients about what makes a great photograph? Do you think one's capable of identifying certain characteristics in a photograph that make it a work of art or a truly great picture?

A: I'm not sure there is any formula to identifying what makes a great picture. I could name several elements that excite me and one of those is surprise, sometimes. It's the way someone looks into the camera and the sincerity that's projected, that's very important. And that's a great deal about what photography is about. What is being projected? Because photography especially portraits of individuals, it's not just the photographer. It's the photographer and the subject and it's how that photographer has connected with their subject. That's a great deal of what photography means to me.

Q: Tell me about the body of photographs you have been working on for many, many years and which you refer to as "FREEZE FRAME".

A: I'm a guy who has worked around a lot of movies, for about fifty years, by the way. And that's what's represented in the book and also in the exhibitions of "FREEZE FRAME." How did this come about? Well, it all started strangely in Rome. The year was 2006 and they were having their first film festival. This great city, which has been very much part of cinema, since the beginning, had never had a film festival. To make a long story short, there was an exhibition of my work down there and that evolved to become "FREEZE FRAME" the book, and also the exhibit. It's been very successful because I feel very passionate about what I've been able to do on many film sets. People who have worked on movie sets for many years know the ups and downs. Every day isn't blockbusters and excitement. Sometimes it's quiet late at night, long hours, and all that sort of thing that film crews live with. What we have in "FREEZE FRAME" is a look across a broad spectrum of what movie making has meant to me. And it's not just the people in front of the camera. Just as important are those people behind the camera. They are very important. There would be no films if it weren't for them.

Q: Did you have any specific goal in mind when you choose the photographs to be included in the book and for the exhibitions?

A: The goal I had was to show what isn't typically shown. Yes, there are some portraits here. But it's predominately the expanse of what happens around the camera and beside the camera, and what's it like being there. Because I know as a child, I had a book at home, when I was very, very young, and there was one picture in there showing how movies were made. It was somebody up there with some leaves being held overhead to create a shadow on the actors. And I saw the boom microphone in there and of course the camera, which in those days, was huge, enormous BNC cameras, and that's what I saw. What it was like surrounding the camera, and frankly that is what I tried to show in this "FREEZE FRAME" project.

Q: A lot of these photographs were accomplished on assignment, correct? (Most of them.) How important is it to you, in terms of what your clients needs are, to try and make sure they get what they're looking for?

A: Well I've been working in this field a long time, as you know. And I wouldn't probably still be doing it if I didn't have a good association with not only the people in front of the camera, but those behind the camera, and those whom I am working for. You have to respect their needs, what they require and how to fulfill their need...but basically you ultimately need to connect with the person in front of the lens and that's the subject. I often say, it's really, it's not me the photographer, it's myself and those out there whom I'm photographing; you have to have a good feeling with them and they have to be comfortable with you. And they have to respect you and what you would do and they have to know that you're there to do the best you possibly can for them and to take this piece of history. You know the history of motion pictures is extraordinary when you think of the power of it. It talks about us. And when I think back thirty years, I mean I can think about working on the Sound of Musicforty years ago and what it was like out there and that's the sort of thing that I've shown. People look at my work from the Sound of Musicfrom the mid-1960's back in Salzburg, and they say, "You were on the Sound of Music? They used to play that for me on videotape, at home, when I was three years of age. I can't believe you were on that!" But I've lived a big piece of this and I want to show it as vividly and as accurately as I can and that's really what the book and the exhibition is about.

Q:

Q: How important is the persona of the celebrity, in the sense that you come to know a Marlon Brando, or Montgomery Cliff, or Elizabeth Taylor or Judy Garland, knowing how we perceive them as performers did it influence you in terms of how you would photograph them? I mean their screen persona before you would show up on the set, or before you would meet them. Did it influence your way of working with them or what you had in mind to try and accomplish in the portrait?

A: Well, when your going to work with a great super star like, ah, Judy Garland, or Brigitte Bardot, or Marilyn Monroe, as far as that goes, you have ideas of what they are like. And then I have found frankly, you sit down with them, or get together with them, and you may see somebody totally different than the person you think you were going to meet. And the more time you have with them the more accurate you can be.

Q: Does anyone particular come to mind that you had that experience with?

A: Well Marilyn Monroe is a good example. I mean, of all the people I've photographed, most people are interested to know what was Marilyn really like? And my answer to that is that I'd like to be able to tell you she was XX and X, but she wasn't. She was many things. She was a changing personality. I was with her on three different occasions and I met three different people. Now, Elizabeth Taylor, she was the one who really got me started photographing celebrities. That's an interesting story. I'll tell you very quickly. I was a young photographer at Look magazine. Look was a very big magazine at the beginning of the 60's and I went there when I was just turning twenty-five and I got this great job that sent me all over the world. But I was not brought in to photograph movie people. I was brought in to shoot fashion and other types of things . . . color, which was a big deal in those days. And I was here in California on a beach photographing bathing suits and I got a call from my boss in New York who said, "Go to Las Vegas. Elizabeth Taylor has said she'll do an interview with us but no pictures. You go with the journalist and you see if you can persuade her to let you photograph her." That, essentially, became the beginning of my career because I went with the journalist and I sat quietly during the interview. And I got up at the end of it and I went up to her and I said, "Elizabeth, I'm new at this magazine. Could you imagine what it would mean to me if I had an opportunity to photograph you?" And I shook her hand and I looked directly into those violet eyes and after a couple of seconds of still holding her hand she said, "Uh, okay. Come tomorrow night at 8:30." I went there the next night at 8:30 and took a series of pictures that were really, that's what launched my career photographing celebrities. Because at that time it was after Mike Todd's death and it hadn't really been any new pictures of her for the last couple of years. And I had the pictures and they went all over the world and they went not just on the cover of Look but they were on Elle and publications in Germany...Everywhere...

Q: What did you think about when you made a decision whether you were going to shoot color or black and white film? Having the option of using either film, what would be the reason you would load color or you would load black and white?

A: Truthfully in the early days we often used black and white because the color film was too slow and we couldn't shoot in low light, where we could with black and white. A good example is traveling with Judy Garland in 1961-1962, I shot her in the studio, photographed her with color. And I used lights and everything but when I went on the road with her and I traveled with her for a month, I shot only black and white with a few exceptions on stage. But I shot her here in Los Angeles. She was making a television show with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin called Judy,and that was a very big show that's still remembered. And I went to Berlin with her, Toronto, DC, New York, all these places...always shooting black and white as I traveled around like that. Why? Because I could do it and I could do it in any light. And that was the look of traditional photojournalism in those days.

Q: Could you talk about your state of mind while doing different assignments for different clients, or when you're shooting for yourself as an artist.

A: You put your head into a different place. You know, truthfully, I become different people at different times. For example, if I'm doing a portrait in the studio for a special purpose, to record somebody I will carefully light it. I try to have different feelings; I don't want my photographs to look all the same. Sometimes my portraits will be close, sometimes they will be full length, but it's whom I become at the time of the shoot that matters to me.

Q: What was it like to meet Man Ray and to photograph him, and how did that assignment come to be?

A: My wife, as you know, is French. Francoise and I were working in Paris on a project for a US publication, photographing a famous hotel in the left bank called Leautell in Paris. One of the people who stayed and often lived there was Man Ray and his wife. And as part of the project they said to me on the side, you know, Man Ray stays with us. Would you be interested in photographing him? I couldn't wait to get started! I mean that is pretty special. I went into this very special suite, at the top of the hotel, where Man Ray stayed. He was the greatest photographer, filmmaker, and artist, and sculptor, it goes on and on . . . He could do anything in the days of Picasso. Right up to the time of the Second World War. And then he came back to the United States. But the important thing is, here's a guy from Brooklyn and he ended up in France and he became so French that some people even thought he was French.

Q: You also worked for Irving Penn, correct? Did you learn things from him?

A: I was an assistant for Irving Penn in 1957 beginning of 1958. I learned so much when I worked as an assistant for Irving Penn, I couldn't begin to tell you, what did I learn? What type of things did I learn? Well to begin with, I learned a new respect for photography and photography was suddenly elevated to a new level for me. Here I am, a kid from a small town, having worked for newspapers, etc. and other small studios. But then I got to New York and I was in the studio of Irving Penn. People say, "How did you get that job?" I was persistent. I sent a series of letters.

Q: How long did you work for him?

A: I worked for him about four or five months, because I wasn't making enough money. I had a child and another one on the way and I couldn't afford to work for the $60.00 a week he was paying me. I asked him if he couldn't pay me $100.00 a week and he said I have to think about that. And he came and said I don't think there's enough future in this business for me. Which is kind of unbelievable! In any case, Irving Penn was fantastic because my first day, my first job, when he had just come back from Europe, was sitting there with a pen and ink numbering each of his negatives of Picasso that he'd brought back. The Picasso pictures, the great pictures of his with the large hat, those were the pictures. And I was talking with the other assistant that was working with me; I learned so much within the first week. I learned an enormous amount. And then I saw the Vogue editors march in. I had never seen anything of that magnitude in my world. My world changed with Irving Penn. And he was very responsible for that, and I thank him very much for this. Cause I grew up, as a photographer, enormously during that period.

Q: What specifically, or more precisely did you learn from him?

A: Something very important that I learned from Irving Penn was truthfully, the importance of respecting your own work and keeping it, archiving it carefully. And fortunately, I've done this to this day, but that was where it began. Because in my small town photographing babies, etc. it was important, but not as important. And then I learned with Penn you have to think of it as body of work that's going to be left as a documentation of your time. And that's what he did and that really started me on it. And that's why we have this show here (at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences) because I've done that very carefully and I continue to do that. So that's very important, and if it were not for Penn I probably would never have done that.

Q: There's some story I heard, something about a window?

A: Okay, yeah. This is a very funny story. This is a story people tell me. And I listen to the story and I say I think I know something about that. Quickly, here's this kid from a small town, working in New York, gets a big brake. Douglas Kirkland and I'm skinny and energetic and really want to please, and Penn was out of town for a couple of days. And I looked around. I was looking for work; I didn't just want to sit around. So what do I do? I got ladders and everything and cleaned all the windows in this huge studio. They were like fifteen or twenty feet high. I'm cleaning it, scrubbing it; I want everything to sparkle when he came back...and I expected to get this wonderful great reward and thank you, etc. What happened? Just the opposite! He came in and he said, ""What happened with our windows??" And he used available light coming through those windows and he felt they had just gotten right. There was certain diffusion as a result of all the New York dust that was all over them and I had taken that away. Anyway, he did survive it, and the strange thing is occasionally people will come up to me and say, "Did you work for Irving Penn? Ever hear the story about the guy who cleaned the windows? I say yeah...that was me.

Q:

Q: Talking about light, which is such an important part of our work as photographers, what are your feelings about light? Is there a way you can articulate that? Because, I know your really quite good with it. And when you do your own studio lighting, how do you match up your lighting package, so to speak, with interpreting the personality of the person your photographing?

A: Well truthfully, you have it in cinema. You have Cinema Noir. You have bright, MGM-type musicals, open lighting. No shadows . . . No, in Cinema there's all types of lighting...but also I think as a photographer you should apply the same devices. In other words, you create a different sense with your lights. Your lights, the lights that we have, are your paintbrushes as a photographer. And that's the way I feel about it. And I'm not afraid of lighting. Some people are afraid of it. Strangely, I've know photographers to figure out one way to make a picture and they essentially measure the distance's and they don't want that soft box or umbrella to be at any other spot because they know they can get a picture that way. They're scared of it. I'm not frightened of lighting. That is, as I said, my paintbrush and my pencil, that's what I work with.

Q: What do you think, looking back on your career, was one of the very toughest assignments you ever had?

A: You know it's interesting. Uh, the toughest assignments, uh, Frankly, probably the toughest assignment for me was, ultimately, it worked out very well, but it was photographing Marilyn Monroe. That was really frightening for me because I was very new at Look magazine, I had been there actually a little over one year, a year and a half and it was November 1961. They had this special issue of the magazine. It was going to be for their twenty-fifth year edition. It was a big deal. And they had connected me with Marilyn and so truthfully I had, my attitude as a young man was, I could do anything. I felt like I was, like, Superman, maybe. Many of us feel that way when we're beginning, which is good. In any case I felt that way, but then after meeting her and starting to think about it, coming from New York out here in L.A. with a few days in between meeting her and doing the shoot, I started to say, have I over-sold myself? I have promised to do something maybe that I can't pull off? And so that became for that moment the most difficult.

Q: I remember you telling me at one time that it was her idea to use the white silk sheets. How did that set get built? What was the story behind how that set got built?

A: Well it was a very simple set frankly, it wasn't really a set in a sense, except we needed an incredible picture of Marilyn, we needed really one picture... to show the essence of Marilyn Monroe. And I talked with her and frankly, as a young man, I wanted something that sizzled, that's the kind of guy I was, and Marilyn Monroe being the greatest sex symbol of the era and she was going to be there with me...so if I didn't get something like that out of her I had not done my job, I felt. So that's what I expected of myself. But you know I came from a small town, went to Sunday school on Sundays and things like that, and how am I going to tell Marilyn Monroe I really want a big picture like that? And the interesting thing is, I sat with her and she was very much on the first meeting like the "Girl Next Door," and she said to me, she made it easy for me. She said, "I know what we need, I should be lying on a bed with nothing on and just have a white silk sheet there." That will do, thank you very much. And that was how it happened.

Q: There were certain angles that you used, like shooting straight down. Was that her idea also?

A: I shot straight down, and I liked that idea, but the interesting thing is that I adapt myself to wherever I am. Some photographers say, "I have to have this, I have to have that." I will look around me and I will find I can use a chair, a window. In that case it was a balcony. It happened to be right in the studio and I was able to put a bed right under that balcony and I could shoot with my Hasselbald over the side and that's how it happened. I mean, but ultimately what's most important is what projected between us, because it's not just, it's not just me. I keep saying that. It was Marilyn. And she had to play to the camera and she loved still photographers. I have always believed she liked stills more than movies because she could create in front of a still camera. She wasn't locked into a script, or having a boom mike looking at her, or doing retakes and things like that. And so she was really good for the still photographer and she liked still photographers and did very well with them. Many, many still photographers, and I was one of the last ones to work with her Well I was very lucky, here I was in November of 1961 . . . She died the following August and she had been ill, and she was now coming back. Interesting thing is she was afraid her breasts looked too small. That's because she had been sick and she had lost weight. When she had the weight she was afraid she looked too heavy. So there was no winning for Marilyn in many ways. But anyway Marilyn was very special and I was able to get my work and it worked out incredibly because we connected and she was projecting toward the camera. You know what she was doing? She was really seducing the camera. And I happened to be the guy there beside it. And that's what she did and that's what you see in these pictures if you look at them.

Douglas Kirkland's book "FREEZE FRAME" is available through Glitterati Publishing.

Douglas Kirkland is one of the most respected and celebrated photographers of the last fifty years. His career and the people he has photographed are legendary. At age twenty-four, Kirkland was hired as a staff photographer for Look magazine and became famous for his 1961 photos of Marilyn Monroe. He continues to accomplish memorable images today that deal with the entertainment industry and he also shoots for prestigious magazines such as Vanity Fair. This interview was conducted at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences where his photographs were on display.

Q: In simple terms could you explain your beginnings as a photographer? What age were you when you started taking pictures? What was your first camera like? When did you start working in the darkroom?

A: Ok. I started working in photography at a very young age, I lived in a very small town up in Canada, 7000 people, called Fort Erie, right opposite Buffalo, New York, and I was a kid with dreams. And I've been able to live those dreams very much, more even than I would have ever imagined. When I was ten I took my first picture with a box brownie of my family out in front of the house on a Christmas day, a really cold Christmas day, Click! One frame that's indelibly locked in my mind. The affect of that, two years later, I was starting to work with the speed graphic, a big 4x5 camera with sheet films. I was about twelve years old when I started, but I really got working more when I was about fourteen, but I took my first picture at ten, a single image. At fourteen, I was working with a local photo studio after school and on Saturdays and they had me doing all sorts of things; photographing babies, photographing organization's meetings, photographing occasionally for the small town newspaper, The Times Review, that was a big deal, a weekly newspaper.

Q: Let me ask you, what do you think makes photography special? I mean what makes it different from, say, the other arts, such as painting or sculpture or literature?

A: Well Tony, I'm in love with all the arts. There's no question of that, and photography for me is the most embracing because I have made films at one time, briefly. And the problem with that is you can't just pick up the camera any day and go out and shoot, which you can as a still photographer. And that's why I have a special love for still photography. You don't have to cut a deal. You don't have to get a group together to shoot. It's becoming simpler today as we see right here where I sit. You can do much. Yes, but my great love is still photography because it's very hands on. As I did in the early days, you can go into the darkroom, develop your film, make your prints, blow them up, explore and discover, find errors, make mistakes and then redo it and keep learning. And that's what I do today with digital cameras, I work with digital as well as film, but when I work with digital I'm on to the computer. That is so igniting! It just ignites me. It sets me up. It's truly exciting!

Q: Do you think it's possible to describe the ingredients about what makes a great photograph? Do you think one's capable of identifying certain characteristics in a photograph that make it a work of art or a truly great picture?

A: I'm not sure there is any formula to identifying what makes a great picture. I could name several elements that excite me and one of those is surprise, sometimes. It's the way someone looks into the camera and the sincerity that's projected, that's very important. And that's a great deal about what photography is about. What is being projected? Because photography especially portraits of individuals, it's not just the photographer. It's the photographer and the subject and it's how that photographer has connected with their subject. That's a great deal of what photography means to me.

Q: Tell me about the body of photographs you have been working on for many, many years and which you refer to as "FREEZE FRAME".

A: I'm a guy who has worked around a lot of movies, for about fifty years, by the way. And that's what's represented in the book and also in the exhibitions of "FREEZE FRAME." How did this come about? Well, it all started strangely in Rome. The year was 2006 and they were having their first film festival. This great city, which has been very much part of cinema, since the beginning, had never had a film festival. To make a long story short, there was an exhibition of my work down there and that evolved to become "FREEZE FRAME" the book, and also the exhibit. It's been very successful because I feel very passionate about what I've been able to do on many film sets. People who have worked on movie sets for many years know the ups and downs. Every day isn't blockbusters and excitement. Sometimes it's quiet late at night, long hours, and all that sort of thing that film crews live with. What we have in "FREEZE FRAME" is a look across a broad spectrum of what movie making has meant to me. And it's not just the people in front of the camera. Just as important are those people behind the camera. They are very important. There would be no films if it weren't for them.

Q: Did you have any specific goal in mind when you choose the photographs to be included in the book and for the exhibitions?

A: The goal I had was to show what isn't typically shown. Yes, there are some portraits here. But it's predominately the expanse of what happens around the camera and beside the camera, and what's it like being there. Because I know as a child, I had a book at home, when I was very, very young, and there was one picture in there showing how movies were made. It was somebody up there with some leaves being held overhead to create a shadow on the actors. And I saw the boom microphone in there and of course the camera, which in those days, was huge, enormous BNC cameras, and that's what I saw. What it was like surrounding the camera, and frankly that is what I tried to show in this "FREEZE FRAME" project.

Q: A lot of these photographs were accomplished on assignment, correct? (Most of them.) How important is it to you, in terms of what your clients needs are, to try and make sure they get what they're looking for?

A: Well I've been working in this field a long time, as you know. And I wouldn't probably still be doing it if I didn't have a good association with not only the people in front of the camera, but those behind the camera, and those whom I am working for. You have to respect their needs, what they require and how to fulfill their need...but basically you ultimately need to connect with the person in front of the lens and that's the subject. I often say, it's really, it's not me the photographer, it's myself and those out there whom I'm photographing; you have to have a good feeling with them and they have to be comfortable with you. And they have to respect you and what you would do and they have to know that you're there to do the best you possibly can for them and to take this piece of history. You know the history of motion pictures is extraordinary when you think of the power of it. It talks about us. And when I think back thirty years, I mean I can think about working on the Sound of Musicforty years ago and what it was like out there and that's the sort of thing that I've shown. People look at my work from the Sound of Musicfrom the mid-1960's back in Salzburg, and they say, "You were on the Sound of Music? They used to play that for me on videotape, at home, when I was three years of age. I can't believe you were on that!" But I've lived a big piece of this and I want to show it as vividly and as accurately as I can and that's really what the book and the exhibition is about.

Douglas Kirkland is one of the most respected and celebrated photographers of the last fifty years. His career and the people he has photographed are legendary. At age twenty-four, Kirkland was hired as a staff photographer for Look magazine and became famous for his 1961 photos of Marilyn Monroe. He continues to accomplish memorable images today that deal with the entertainment industry and he also shoots for prestigious magazines such as Vanity Fair. This interview was conducted at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences where his photographs were on display.

Q: In simple terms could you explain your beginnings as a photographer? What age were you when you started taking pictures? What was your first camera like? When did you start working in the darkroom?

A: Ok. I started working in photography at a very young age, I lived in a very small town up in Canada, 7000 people, called Fort Erie, right opposite Buffalo, New York, and I was a kid with dreams. And I've been able to live those dreams very much, more even than I would have ever imagined. When I was ten I took my first picture with a box brownie of my family out in front of the house on a Christmas day, a really cold Christmas day, Click! One frame that's indelibly locked in my mind. The affect of that, two years later, I was starting to work with the speed graphic, a big 4x5 camera with sheet films. I was about twelve years old when I started, but I really got working more when I was about fourteen, but I took my first picture at ten, a single image. At fourteen, I was working with a local photo studio after school and on Saturdays and they had me doing all sorts of things; photographing babies, photographing organization's meetings, photographing occasionally for the small town newspaper, The Times Review, that was a big deal, a weekly newspaper.

Q: Let me ask you, what do you think makes photography special? I mean what makes it different from, say, the other arts, such as painting or sculpture or literature?

A: Well Tony, I'm in love with all the arts. There's no question of that, and photography for me is the most embracing because I have made films at one time, briefly. And the problem with that is you can't just pick up the camera any day and go out and shoot, which you can as a still photographer. And that's why I have a special love for still photography. You don't have to cut a deal. You don't have to get a group together to shoot. It's becoming simpler today as we see right here where I sit. You can do much. Yes, but my great love is still photography because it's very hands on. As I did in the early days, you can go into the darkroom, develop your film, make your prints, blow them up, explore and discover, find errors, make mistakes and then redo it and keep learning. And that's what I do today with digital cameras, I work with digital as well as film, but when I work with digital I'm on to the computer. That is so igniting! It just ignites me. It sets me up. It's truly exciting!

Q: Do you think it's possible to describe the ingredients about what makes a great photograph? Do you think one's capable of identifying certain characteristics in a photograph that make it a work of art or a truly great picture?

A: I'm not sure there is any formula to identifying what makes a great picture. I could name several elements that excite me and one of those is surprise, sometimes. It's the way someone looks into the camera and the sincerity that's projected, that's very important. And that's a great deal about what photography is about. What is being projected? Because photography especially portraits of individuals, it's not just the photographer. It's the photographer and the subject and it's how that photographer has connected with their subject. That's a great deal of what photography means to me.

Q: Tell me about the body of photographs you have been working on for many, many years and which you refer to as "FREEZE FRAME".

A: I'm a guy who has worked around a lot of movies, for about fifty years, by the way. And that's what's represented in the book and also in the exhibitions of "FREEZE FRAME." How did this come about? Well, it all started strangely in Rome. The year was 2006 and they were having their first film festival. This great city, which has been very much part of cinema, since the beginning, had never had a film festival. To make a long story short, there was an exhibition of my work down there and that evolved to become "FREEZE FRAME" the book, and also the exhibit. It's been very successful because I feel very passionate about what I've been able to do on many film sets. People who have worked on movie sets for many years know the ups and downs. Every day isn't blockbusters and excitement. Sometimes it's quiet late at night, long hours, and all that sort of thing that film crews live with. What we have in "FREEZE FRAME" is a look across a broad spectrum of what movie making has meant to me. And it's not just the people in front of the camera. Just as important are those people behind the camera. They are very important. There would be no films if it weren't for them.

Q: Did you have any specific goal in mind when you choose the photographs to be included in the book and for the exhibitions?

A: The goal I had was to show what isn't typically shown. Yes, there are some portraits here. But it's predominately the expanse of what happens around the camera and beside the camera, and what's it like being there. Because I know as a child, I had a book at home, when I was very, very young, and there was one picture in there showing how movies were made. It was somebody up there with some leaves being held overhead to create a shadow on the actors. And I saw the boom microphone in there and of course the camera, which in those days, was huge, enormous BNC cameras, and that's what I saw. What it was like surrounding the camera, and frankly that is what I tried to show in this "FREEZE FRAME" project.

Q: A lot of these photographs were accomplished on assignment, correct? (Most of them.) How important is it to you, in terms of what your clients needs are, to try and make sure they get what they're looking for?

A: Well I've been working in this field a long time, as you know. And I wouldn't probably still be doing it if I didn't have a good association with not only the people in front of the camera, but those behind the camera, and those whom I am working for. You have to respect their needs, what they require and how to fulfill their need...but basically you ultimately need to connect with the person in front of the lens and that's the subject. I often say, it's really, it's not me the photographer, it's myself and those out there whom I'm photographing; you have to have a good feeling with them and they have to be comfortable with you. And they have to respect you and what you would do and they have to know that you're there to do the best you possibly can for them and to take this piece of history. You know the history of motion pictures is extraordinary when you think of the power of it. It talks about us. And when I think back thirty years, I mean I can think about working on the Sound of Musicforty years ago and what it was like out there and that's the sort of thing that I've shown. People look at my work from the Sound of Musicfrom the mid-1960's back in Salzburg, and they say, "You were on the Sound of Music? They used to play that for me on videotape, at home, when I was three years of age. I can't believe you were on that!" But I've lived a big piece of this and I want to show it as vividly and as accurately as I can and that's really what the book and the exhibition is about.

Q: How important is the persona of the celebrity, in the sense that you come to know a Marlon Brando, or Montgomery Cliff, or Elizabeth Taylor or Judy Garland, knowing how we perceive them as performers did it influence you in terms of how you would photograph them? I mean their screen persona before you would show up on the set, or before you would meet them. Did it influence your way of working with them or what you had in mind to try and accomplish in the portrait?

A: Well, when your going to work with a great super star like, ah, Judy Garland, or Brigitte Bardot, or Marilyn Monroe, as far as that goes, you have ideas of what they are like. And then I have found frankly, you sit down with them, or get together with them, and you may see somebody totally different than the person you think you were going to meet. And the more time you have with them the more accurate you can be.

Q: Does anyone particular come to mind that you had that experience with?

A: Well Marilyn Monroe is a good example. I mean, of all the people I've photographed, most people are interested to know what was Marilyn really like? And my answer to that is that I'd like to be able to tell you she was XX and X, but she wasn't. She was many things. She was a changing personality. I was with her on three different occasions and I met three different people. Now, Elizabeth Taylor, she was the one who really got me started photographing celebrities. That's an interesting story. I'll tell you very quickly. I was a young photographer at Look magazine. Look was a very big magazine at the beginning of the 60's and I went there when I was just turning twenty-five and I got this great job that sent me all over the world. But I was not brought in to photograph movie people. I was brought in to shoot fashion and other types of things . . . color, which was a big deal in those days. And I was here in California on a beach photographing bathing suits and I got a call from my boss in New York who said, "Go to Las Vegas. Elizabeth Taylor has said she'll do an interview with us but no pictures. You go with the journalist and you see if you can persuade her to let you photograph her." That, essentially, became the beginning of my career because I went with the journalist and I sat quietly during the interview. And I got up at the end of it and I went up to her and I said, "Elizabeth, I'm new at this magazine. Could you imagine what it would mean to me if I had an opportunity to photograph you?" And I shook her hand and I looked directly into those violet eyes and after a couple of seconds of still holding her hand she said, "Uh, okay. Come tomorrow night at 8:30." I went there the next night at 8:30 and took a series of pictures that were really, that's what launched my career photographing celebrities. Because at that time it was after Mike Todd's death and it hadn't really been any new pictures of her for the last couple of years. And I had the pictures and they went all over the world and they went not just on the cover of Look but they were on Elle and publications in Germany...Everywhere...

Q: What did you think about when you made a decision whether you were going to shoot color or black and white film? Having the option of using either film, what would be the reason you would load color or you would load black and white?

A: Truthfully in the early days we often used black and white because the color film was too slow and we couldn't shoot in low light, where we could with black and white. A good example is traveling with Judy Garland in 1961-1962, I shot her in the studio, photographed her with color. And I used lights and everything but when I went on the road with her and I traveled with her for a month, I shot only black and white with a few exceptions on stage. But I shot her here in Los Angeles. She was making a television show with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin called Judy,and that was a very big show that's still remembered. And I went to Berlin with her, Toronto, DC, New York, all these places...always shooting black and white as I traveled around like that. Why? Because I could do it and I could do it in any light. And that was the look of traditional photojournalism in those days.

Q: Could you talk about your state of mind while doing different assignments for different clients, or when you're shooting for yourself as an artist.

A: You put your head into a different place. You know, truthfully, I become different people at different times. For example, if I'm doing a portrait in the studio for a special purpose, to record somebody I will carefully light it. I try to have different feelings; I don't want my photographs to look all the same. Sometimes my portraits will be close, sometimes they will be full length, but it's whom I become at the time of the shoot that matters to me.

Q: What was it like to meet Man Ray and to photograph him, and how did that assignment come to be?

A: My wife, as you know, is French. Francoise and I were working in Paris on a project for a US publication, photographing a famous hotel in the left bank called Leautell in Paris. One of the people who stayed and often lived there was Man Ray and his wife. And as part of the project they said to me on the side, you know, Man Ray stays with us. Would you be interested in photographing him? I couldn't wait to get started! I mean that is pretty special. I went into this very special suite, at the top of the hotel, where Man Ray stayed. He was the greatest photographer, filmmaker, and artist, and sculptor, it goes on and on . . . He could do anything in the days of Picasso. Right up to the time of the Second World War. And then he came back to the United States. But the important thing is, here's a guy from Brooklyn and he ended up in France and he became so French that some people even thought he was French.

Q: You also worked for Irving Penn, correct? Did you learn things from him?

A: I was an assistant for Irving Penn in 1957 beginning of 1958. I learned so much when I worked as an assistant for Irving Penn, I couldn't begin to tell you, what did I learn? What type of things did I learn? Well to begin with, I learned a new respect for photography and photography was suddenly elevated to a new level for me. Here I am, a kid from a small town, having worked for newspapers, etc. and other small studios. But then I got to New York and I was in the studio of Irving Penn. People say, "How did you get that job?" I was persistent. I sent a series of letters.

Q: How long did you work for him?

A: I worked for him about four or five months, because I wasn't making enough money. I had a child and another one on the way and I couldn't afford to work for the $60.00 a week he was paying me. I asked him if he couldn't pay me $100.00 a week and he said I have to think about that. And he came and said I don't think there's enough future in this business for me. Which is kind of unbelievable! In any case, Irving Penn was fantastic because my first day, my first job, when he had just come back from Europe, was sitting there with a pen and ink numbering each of his negatives of Picasso that he'd brought back. The Picasso pictures, the great pictures of his with the large hat, those were the pictures. And I was talking with the other assistant that was working with me; I learned so much within the first week. I learned an enormous amount. And then I saw the Vogue editors march in. I had never seen anything of that magnitude in my world. My world changed with Irving Penn. And he was very responsible for that, and I thank him very much for this. Cause I grew up, as a photographer, enormously during that period.

Q: What specifically, or more precisely did you learn from him?

A: Something very important that I learned from Irving Penn was truthfully, the importance of respecting your own work and keeping it, archiving it carefully. And fortunately, I've done this to this day, but that was where it began. Because in my small town photographing babies, etc. it was important, but not as important. And then I learned with Penn you have to think of it as body of work that's going to be left as a documentation of your time. And that's what he did and that really started me on it. And that's why we have this show here (at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences) because I've done that very carefully and I continue to do that. So that's very important, and if it were not for Penn I probably would never have done that.

Q: There's some story I heard, something about a window?

A: Okay, yeah. This is a very funny story. This is a story people tell me. And I listen to the story and I say I think I know something about that. Quickly, here's this kid from a small town, working in New York, gets a big brake. Douglas Kirkland and I'm skinny and energetic and really want to please, and Penn was out of town for a couple of days. And I looked around. I was looking for work; I didn't just want to sit around. So what do I do? I got ladders and everything and cleaned all the windows in this huge studio. They were like fifteen or twenty feet high. I'm cleaning it, scrubbing it; I want everything to sparkle when he came back...and I expected to get this wonderful great reward and thank you, etc. What happened? Just the opposite! He came in and he said, ""What happened with our windows??" And he used available light coming through those windows and he felt they had just gotten right. There was certain diffusion as a result of all the New York dust that was all over them and I had taken that away. Anyway, he did survive it, and the strange thing is occasionally people will come up to me and say, "Did you work for Irving Penn? Ever hear the story about the guy who cleaned the windows? I say yeah...that was me.

Q: How important is the persona of the celebrity, in the sense that you come to know a Marlon Brando, or Montgomery Cliff, or Elizabeth Taylor or Judy Garland, knowing how we perceive them as performers did it influence you in terms of how you would photograph them? I mean their screen persona before you would show up on the set, or before you would meet them. Did it influence your way of working with them or what you had in mind to try and accomplish in the portrait?

A: Well, when your going to work with a great super star like, ah, Judy Garland, or Brigitte Bardot, or Marilyn Monroe, as far as that goes, you have ideas of what they are like. And then I have found frankly, you sit down with them, or get together with them, and you may see somebody totally different than the person you think you were going to meet. And the more time you have with them the more accurate you can be.

Q: Does anyone particular come to mind that you had that experience with?

A: Well Marilyn Monroe is a good example. I mean, of all the people I've photographed, most people are interested to know what was Marilyn really like? And my answer to that is that I'd like to be able to tell you she was XX and X, but she wasn't. She was many things. She was a changing personality. I was with her on three different occasions and I met three different people. Now, Elizabeth Taylor, she was the one who really got me started photographing celebrities. That's an interesting story. I'll tell you very quickly. I was a young photographer at Look magazine. Look was a very big magazine at the beginning of the 60's and I went there when I was just turning twenty-five and I got this great job that sent me all over the world. But I was not brought in to photograph movie people. I was brought in to shoot fashion and other types of things . . . color, which was a big deal in those days. And I was here in California on a beach photographing bathing suits and I got a call from my boss in New York who said, "Go to Las Vegas. Elizabeth Taylor has said she'll do an interview with us but no pictures. You go with the journalist and you see if you can persuade her to let you photograph her." That, essentially, became the beginning of my career because I went with the journalist and I sat quietly during the interview. And I got up at the end of it and I went up to her and I said, "Elizabeth, I'm new at this magazine. Could you imagine what it would mean to me if I had an opportunity to photograph you?" And I shook her hand and I looked directly into those violet eyes and after a couple of seconds of still holding her hand she said, "Uh, okay. Come tomorrow night at 8:30." I went there the next night at 8:30 and took a series of pictures that were really, that's what launched my career photographing celebrities. Because at that time it was after Mike Todd's death and it hadn't really been any new pictures of her for the last couple of years. And I had the pictures and they went all over the world and they went not just on the cover of Look but they were on Elle and publications in Germany...Everywhere...

Q: What did you think about when you made a decision whether you were going to shoot color or black and white film? Having the option of using either film, what would be the reason you would load color or you would load black and white?

A: Truthfully in the early days we often used black and white because the color film was too slow and we couldn't shoot in low light, where we could with black and white. A good example is traveling with Judy Garland in 1961-1962, I shot her in the studio, photographed her with color. And I used lights and everything but when I went on the road with her and I traveled with her for a month, I shot only black and white with a few exceptions on stage. But I shot her here in Los Angeles. She was making a television show with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin called Judy,and that was a very big show that's still remembered. And I went to Berlin with her, Toronto, DC, New York, all these places...always shooting black and white as I traveled around like that. Why? Because I could do it and I could do it in any light. And that was the look of traditional photojournalism in those days.

Q: Could you talk about your state of mind while doing different assignments for different clients, or when you're shooting for yourself as an artist.

A: You put your head into a different place. You know, truthfully, I become different people at different times. For example, if I'm doing a portrait in the studio for a special purpose, to record somebody I will carefully light it. I try to have different feelings; I don't want my photographs to look all the same. Sometimes my portraits will be close, sometimes they will be full length, but it's whom I become at the time of the shoot that matters to me.

Q: What was it like to meet Man Ray and to photograph him, and how did that assignment come to be?

A: My wife, as you know, is French. Francoise and I were working in Paris on a project for a US publication, photographing a famous hotel in the left bank called Leautell in Paris. One of the people who stayed and often lived there was Man Ray and his wife. And as part of the project they said to me on the side, you know, Man Ray stays with us. Would you be interested in photographing him? I couldn't wait to get started! I mean that is pretty special. I went into this very special suite, at the top of the hotel, where Man Ray stayed. He was the greatest photographer, filmmaker, and artist, and sculptor, it goes on and on . . . He could do anything in the days of Picasso. Right up to the time of the Second World War. And then he came back to the United States. But the important thing is, here's a guy from Brooklyn and he ended up in France and he became so French that some people even thought he was French.

Q: You also worked for Irving Penn, correct? Did you learn things from him?

A: I was an assistant for Irving Penn in 1957 beginning of 1958. I learned so much when I worked as an assistant for Irving Penn, I couldn't begin to tell you, what did I learn? What type of things did I learn? Well to begin with, I learned a new respect for photography and photography was suddenly elevated to a new level for me. Here I am, a kid from a small town, having worked for newspapers, etc. and other small studios. But then I got to New York and I was in the studio of Irving Penn. People say, "How did you get that job?" I was persistent. I sent a series of letters.

Q: How long did you work for him?

A: I worked for him about four or five months, because I wasn't making enough money. I had a child and another one on the way and I couldn't afford to work for the $60.00 a week he was paying me. I asked him if he couldn't pay me $100.00 a week and he said I have to think about that. And he came and said I don't think there's enough future in this business for me. Which is kind of unbelievable! In any case, Irving Penn was fantastic because my first day, my first job, when he had just come back from Europe, was sitting there with a pen and ink numbering each of his negatives of Picasso that he'd brought back. The Picasso pictures, the great pictures of his with the large hat, those were the pictures. And I was talking with the other assistant that was working with me; I learned so much within the first week. I learned an enormous amount. And then I saw the Vogue editors march in. I had never seen anything of that magnitude in my world. My world changed with Irving Penn. And he was very responsible for that, and I thank him very much for this. Cause I grew up, as a photographer, enormously during that period.

Q: What specifically, or more precisely did you learn from him?

A: Something very important that I learned from Irving Penn was truthfully, the importance of respecting your own work and keeping it, archiving it carefully. And fortunately, I've done this to this day, but that was where it began. Because in my small town photographing babies, etc. it was important, but not as important. And then I learned with Penn you have to think of it as body of work that's going to be left as a documentation of your time. And that's what he did and that really started me on it. And that's why we have this show here (at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences) because I've done that very carefully and I continue to do that. So that's very important, and if it were not for Penn I probably would never have done that.

Q: There's some story I heard, something about a window?

A: Okay, yeah. This is a very funny story. This is a story people tell me. And I listen to the story and I say I think I know something about that. Quickly, here's this kid from a small town, working in New York, gets a big brake. Douglas Kirkland and I'm skinny and energetic and really want to please, and Penn was out of town for a couple of days. And I looked around. I was looking for work; I didn't just want to sit around. So what do I do? I got ladders and everything and cleaned all the windows in this huge studio. They were like fifteen or twenty feet high. I'm cleaning it, scrubbing it; I want everything to sparkle when he came back...and I expected to get this wonderful great reward and thank you, etc. What happened? Just the opposite! He came in and he said, ""What happened with our windows??" And he used available light coming through those windows and he felt they had just gotten right. There was certain diffusion as a result of all the New York dust that was all over them and I had taken that away. Anyway, he did survive it, and the strange thing is occasionally people will come up to me and say, "Did you work for Irving Penn? Ever hear the story about the guy who cleaned the windows? I say yeah...that was me.

Q: Talking about light, which is such an important part of our work as photographers, what are your feelings about light? Is there a way you can articulate that? Because, I know your really quite good with it. And when you do your own studio lighting, how do you match up your lighting package, so to speak, with interpreting the personality of the person your photographing?

A: Well truthfully, you have it in cinema. You have Cinema Noir. You have bright, MGM-type musicals, open lighting. No shadows . . . No, in Cinema there's all types of lighting...but also I think as a photographer you should apply the same devices. In other words, you create a different sense with your lights. Your lights, the lights that we have, are your paintbrushes as a photographer. And that's the way I feel about it. And I'm not afraid of lighting. Some people are afraid of it. Strangely, I've know photographers to figure out one way to make a picture and they essentially measure the distance's and they don't want that soft box or umbrella to be at any other spot because they know they can get a picture that way. They're scared of it. I'm not frightened of lighting. That is, as I said, my paintbrush and my pencil, that's what I work with.

Q: What do you think, looking back on your career, was one of the very toughest assignments you ever had?

A: You know it's interesting. Uh, the toughest assignments, uh, Frankly, probably the toughest assignment for me was, ultimately, it worked out very well, but it was photographing Marilyn Monroe. That was really frightening for me because I was very new at Look magazine, I had been there actually a little over one year, a year and a half and it was November 1961. They had this special issue of the magazine. It was going to be for their twenty-fifth year edition. It was a big deal. And they had connected me with Marilyn and so truthfully I had, my attitude as a young man was, I could do anything. I felt like I was, like, Superman, maybe. Many of us feel that way when we're beginning, which is good. In any case I felt that way, but then after meeting her and starting to think about it, coming from New York out here in L.A. with a few days in between meeting her and doing the shoot, I started to say, have I over-sold myself? I have promised to do something maybe that I can't pull off? And so that became for that moment the most difficult.

Q: I remember you telling me at one time that it was her idea to use the white silk sheets. How did that set get built? What was the story behind how that set got built?

A: Well it was a very simple set frankly, it wasn't really a set in a sense, except we needed an incredible picture of Marilyn, we needed really one picture... to show the essence of Marilyn Monroe. And I talked with her and frankly, as a young man, I wanted something that sizzled, that's the kind of guy I was, and Marilyn Monroe being the greatest sex symbol of the era and she was going to be there with me...so if I didn't get something like that out of her I had not done my job, I felt. So that's what I expected of myself. But you know I came from a small town, went to Sunday school on Sundays and things like that, and how am I going to tell Marilyn Monroe I really want a big picture like that? And the interesting thing is, I sat with her and she was very much on the first meeting like the "Girl Next Door," and she said to me, she made it easy for me. She said, "I know what we need, I should be lying on a bed with nothing on and just have a white silk sheet there." That will do, thank you very much. And that was how it happened.

Q: There were certain angles that you used, like shooting straight down. Was that her idea also?

A: I shot straight down, and I liked that idea, but the interesting thing is that I adapt myself to wherever I am. Some photographers say, "I have to have this, I have to have that." I will look around me and I will find I can use a chair, a window. In that case it was a balcony. It happened to be right in the studio and I was able to put a bed right under that balcony and I could shoot with my Hasselbald over the side and that's how it happened. I mean, but ultimately what's most important is what projected between us, because it's not just, it's not just me. I keep saying that. It was Marilyn. And she had to play to the camera and she loved still photographers. I have always believed she liked stills more than movies because she could create in front of a still camera. She wasn't locked into a script, or having a boom mike looking at her, or doing retakes and things like that. And so she was really good for the still photographer and she liked still photographers and did very well with them. Many, many still photographers, and I was one of the last ones to work with her Well I was very lucky, here I was in November of 1961 . . . She died the following August and she had been ill, and she was now coming back. Interesting thing is she was afraid her breasts looked too small. That's because she had been sick and she had lost weight. When she had the weight she was afraid she looked too heavy. So there was no winning for Marilyn in many ways. But anyway Marilyn was very special and I was able to get my work and it worked out incredibly because we connected and she was projecting toward the camera. You know what she was doing? She was really seducing the camera. And I happened to be the guy there beside it. And that's what she did and that's what you see in these pictures if you look at them.

Douglas Kirkland's book "FREEZE FRAME" is available through Glitterati Publishing.

Q: Talking about light, which is such an important part of our work as photographers, what are your feelings about light? Is there a way you can articulate that? Because, I know your really quite good with it. And when you do your own studio lighting, how do you match up your lighting package, so to speak, with interpreting the personality of the person your photographing?

A: Well truthfully, you have it in cinema. You have Cinema Noir. You have bright, MGM-type musicals, open lighting. No shadows . . . No, in Cinema there's all types of lighting...but also I think as a photographer you should apply the same devices. In other words, you create a different sense with your lights. Your lights, the lights that we have, are your paintbrushes as a photographer. And that's the way I feel about it. And I'm not afraid of lighting. Some people are afraid of it. Strangely, I've know photographers to figure out one way to make a picture and they essentially measure the distance's and they don't want that soft box or umbrella to be at any other spot because they know they can get a picture that way. They're scared of it. I'm not frightened of lighting. That is, as I said, my paintbrush and my pencil, that's what I work with.

Q: What do you think, looking back on your career, was one of the very toughest assignments you ever had?

A: You know it's interesting. Uh, the toughest assignments, uh, Frankly, probably the toughest assignment for me was, ultimately, it worked out very well, but it was photographing Marilyn Monroe. That was really frightening for me because I was very new at Look magazine, I had been there actually a little over one year, a year and a half and it was November 1961. They had this special issue of the magazine. It was going to be for their twenty-fifth year edition. It was a big deal. And they had connected me with Marilyn and so truthfully I had, my attitude as a young man was, I could do anything. I felt like I was, like, Superman, maybe. Many of us feel that way when we're beginning, which is good. In any case I felt that way, but then after meeting her and starting to think about it, coming from New York out here in L.A. with a few days in between meeting her and doing the shoot, I started to say, have I over-sold myself? I have promised to do something maybe that I can't pull off? And so that became for that moment the most difficult.

Q: I remember you telling me at one time that it was her idea to use the white silk sheets. How did that set get built? What was the story behind how that set got built?

A: Well it was a very simple set frankly, it wasn't really a set in a sense, except we needed an incredible picture of Marilyn, we needed really one picture... to show the essence of Marilyn Monroe. And I talked with her and frankly, as a young man, I wanted something that sizzled, that's the kind of guy I was, and Marilyn Monroe being the greatest sex symbol of the era and she was going to be there with me...so if I didn't get something like that out of her I had not done my job, I felt. So that's what I expected of myself. But you know I came from a small town, went to Sunday school on Sundays and things like that, and how am I going to tell Marilyn Monroe I really want a big picture like that? And the interesting thing is, I sat with her and she was very much on the first meeting like the "Girl Next Door," and she said to me, she made it easy for me. She said, "I know what we need, I should be lying on a bed with nothing on and just have a white silk sheet there." That will do, thank you very much. And that was how it happened.

Q: There were certain angles that you used, like shooting straight down. Was that her idea also?

A: I shot straight down, and I liked that idea, but the interesting thing is that I adapt myself to wherever I am. Some photographers say, "I have to have this, I have to have that." I will look around me and I will find I can use a chair, a window. In that case it was a balcony. It happened to be right in the studio and I was able to put a bed right under that balcony and I could shoot with my Hasselbald over the side and that's how it happened. I mean, but ultimately what's most important is what projected between us, because it's not just, it's not just me. I keep saying that. It was Marilyn. And she had to play to the camera and she loved still photographers. I have always believed she liked stills more than movies because she could create in front of a still camera. She wasn't locked into a script, or having a boom mike looking at her, or doing retakes and things like that. And so she was really good for the still photographer and she liked still photographers and did very well with them. Many, many still photographers, and I was one of the last ones to work with her Well I was very lucky, here I was in November of 1961 . . . She died the following August and she had been ill, and she was now coming back. Interesting thing is she was afraid her breasts looked too small. That's because she had been sick and she had lost weight. When she had the weight she was afraid she looked too heavy. So there was no winning for Marilyn in many ways. But anyway Marilyn was very special and I was able to get my work and it worked out incredibly because we connected and she was projecting toward the camera. You know what she was doing? She was really seducing the camera. And I happened to be the guy there beside it. And that's what she did and that's what you see in these pictures if you look at them.

Douglas Kirkland's book "FREEZE FRAME" is available through Glitterati Publishing.