S

Surfing is one of the oldest and most enjoyed sports on our planet. Waves are like liquid sculpture, they move through the ocean with ethereal beauty. The art of wave riding (and for many surfers it becomes a type of religious dedication) is a blending of physical talent and personal expression. This is coupled with the reverence for the magnificent power of nature, the ocean in particular.

Jeff Divine is considered one of the finest surfing photographers ever; and that includes the entire history of surf photography. He has produced some of the most inspiring and classic surfing pictures of all time. Jeff Divine is not only a master surf photographer; he is a master photographer. Period.

Divine has dedicated over 40 years to this specific genre of photography. His photographs connect the spiritual powers of nature, a celebration of life and his own deep love of surfing in all of its varied characteristics and with all that encompasses. His work is unequaled. He has numerous books out and his work has been published internationally. His work is exhibited at fine museums and art galleries.

Q:

How did you get started in photography? What was your very first camera? How old were you when you first went into a darkroom? (Jeff is shooting portraits of me while I ask him questions.)

A: In a nutshell, here is a little back round: Before I ever got a camera, my mom was an artist. She went to Mills (College for Women in San Francisco) and she majored in music. I grew up in the art world of La Jolla, California.

My mother was a founder of the La Jolla Museum of Art; she held fundraisers in our backyard. My father was an architect-artist who went to Berkley and built a modernist home in La Jolla Shores. My grandmother was also an artist. She painted watercolors of flowers and hung out in the artist's colony at Balboa Park where she exhibited her work. So, I have that [art] background.

I always like to tell people that I think photography is either in your DNA or it's not in your DNA. It's like a "body chemistry" thing that allows you to form things in this little frame. It's something you either have or you don't. There are other qualities, too, like your personality, what attracts you to different things, and how you interact with people . . . The building blocks, in my case, were "Who Were Your Parents," and my parents all happened to be artists. I kind of lucked out in that sense.

Q:

Q: How old were you when you first started taking pictures?

A: I was 16. I worked at John Cole's Bookstore in La Jolla and some friends of mine were taking surf photos. They would make black & white prints, we'd be standing around, putting our boards away on the racks near our neighbor's house and they would pull up and have these prints with them and say, " Look! I just shot this of Barry Kanaiaupuni at Windansea or, "Here's (David) Nuuhiwa! He's this incredible guy from Hawaii, and here he is, riding the nose!"

For some reason I was so attracted to those 8x10 black & whites! So, I got a camera with the money I earned at the bookstore, and my grandmother subsidized me. The funny thing is that I didn't start right off shooting surf photos. I started shooting like . . . I was attracted to light and reflection, composing lines and other things besides surfing. One day I see a beautiful sunset. I go running up to the Marine Room (restaurant with a view of the La Jolla Cove) and start shooting photos and I align the agave plant in the foreground with those old Portuguese tuna boats that were in La Jolla cove . . . and BOOM! I got a cover of San Diego Magazine! I was self-taught. I had to figure it out. It was hard to learn how to expose Kodachrome-25 color slide film.

Q:

Q: Were you shooting mostly color?

A: Yes, color; color right away. I started going at it all by myself. There was no mentor, nobody else.

Q: Did you read books?

A: The only thing I read at that point in time was the Life (Magazine) series of books on photography, which gave me a context. I was like the "happy-wappy" kid from down south to guys up here at Surfer Magazine and Dana Point. So, by 1967, I started giving them my photos of perfect Black's. Or, because I'd wait before I'd shoot (it might take awhile to shoot one roll of 36 photos, all of them) I would always surf, too. Then I would shoot. Or when I was burned out, I would go shoot. But I always surfed first.

Q:

Q: How do you deal with that now?

A: Now I tend to just shoot. It's a long story because it's evolved. I mean I've been doing it for 45 years. A big middle chunk of my career was becoming more professional about taking surf photos rather than surfing, where you can hurt your ankle or your knee, or get too tired. And then, you can't focus.

As I became more professional over the years, I learned that you've got to focus on taking pictures.

Then, as pro-surfing evolved; the pro-surfers didn't really want me to be surfing with them. They want me to be taking their photos because that means money to them.

Q: So, when did you get your first underwater housing?

A:

A: What happened was I started coming up to Surfer (Magazine) and they liked me. Art Brewer and Ron Stoner were shooting for Surfer. And John Severson was around, but he was starting to bail out to Maui. Stoner was melting down mentally and I was positive and "stoked," as they say; all of a sudden the staff gives me some photo equipment to use, and they suggested I get a water housing for myself, which I did, from Scott Priess.

I started shooting Windansea and Big Rock, etc.

Q: So this was 'way before digital; you were shooting film?

A: Yes. This might have been in 1969 or 1970, when I got my first water housing.

Q: Were you swimming with fins?

A:

A: I had a converse raft with Churchill UDT fins and no leash on the raft. I'd go out to Windansea, Big Rock, La Jolla Shores, which were difficult from the water . . . Go out at Black's . . . Some of the time, I'd swim out. I had to use a manual focus-135mm lens (which is really hard to focus; try it sometime!). The surfer is speeding at you, and the closer they get the harder it gets. You're moving with this and that and worried that the wave is going to hit you. It was very difficult.

Then, I transferred that knowledge and moved to Hawaii in 1971. I was kind of like a water child, growing up near the beach in La Jolla Shores, so it wasn't that hard of a transition to go and do the same thing in Hawaii. But the funny thing was that, doing water shots in Hawaii, I was alone.

Today, you can sit in your car and watch what the other photographers do because there are hoards of them. In my day, I'd sit in my car and get scared because there was the shore break. There's the peak out at Sunset and it's 10-foot feathering offshore. All the experienced surfers look like He-Men. They know what they're doing and they're walking by you all confident and everything, and I'm, like, s---ting myself (laughter)!

Hawaii is so much more powerful than California. We live in a wimpy swirl pond compared to Hawaii - the power and the rip tides. All that energy of the ocean is so different! I'd get my gear together and go stand at the shore break at Sunset going, "Oh s-t! Oh s--t!" You have to time yourself to go out and wait for the lull or you can get completely screwed up in the shore break. It can be very dangerous. It doesn't look that bad, but it can be really rowdy. Once you get over that little -fifteen -twenty-foot zone, its deep water with a big rip through it. You just kick as hard as you can, and the rip drags you over to Kammieland. Then you just head straight across to the peak at Sunset and station yourself, depending on whether you want to shoot the inside or the middle peak, the swell; and that's were it becomes so exciting!

Being a water person, I'm not terrified, just . . . It's such a thrill! Because it's so intense, these big walls and offshore! And these guys are out...

Q:

Q: Would you be in the impact zone? Or close to the impact zone?

A: No, no! That was the thing! With the 135mm lens the whole thing about surf photography is to avoid the impact zone. Being a surfer, you know, all those years your whole thing with surfing is avoiding the impact zone, negotiating the inside reef, and the mid-reef and lining up with the trees on the hill because if you get caught you are screwed...

So you're always negotiating. You're always kicking hard and paddling hard . . . like your housing is in one hand, with one arm, and you're kicking as hard as you can, and the raft is going, "OH NO! OH NO!" (Jeff makes all kinds of funny ocean sounds) "BOOM!" And I go over the falls and take a serious wipeout . . . And then I ground myself again. I see a set come in, and, depending on who it is, what surfer is taking off, I wipe the front of my plexi-front port (a plexi glass cylinder with a water tight plex-face that the lens fits into) making sure there are no water drops on it and station myself; "Manual focus! Manual focus! Shoot!!" It's so many hours out there.

Q:

Q: Was it difficult though with only 36 pictures? Did you have to try to pace yourself at all?

A: Yes, I'd pick and choose who I might shoot, then I'd pick and choose the sets and the direction of the swell. That was really important, because certain directions you know aren't going to pitch out; other ones you know are going to have a nice wall or pitch out, so there was a whole science going on in my head, as a surfer, because I know the ocean.

I'd analyze it every time a set would come in: "Da, da, da . . . Where's Hakman? Where's so and so?" As soon as I'd see my target guy paddling, whoever it might be, Shaun or Rabbit or BK or Ian Cairns or any of those guys, and get ready and carefully pick my shots, anticipate the moment.

What blew my mind, I got my first digital housing a few years ago and I went on a trip to Indo and I say "let freedom ring"! It's like I'm shooting my feet, the sky, (laughter) my friend's paddling by . . . no problem... It was fabulous.

I'd just put the throttle down and, with a wide-angle lens, from when the guy takes off - until he is all the way past me, I could shoot.

There were some guys, in the days of one roll of film with 36 shots, that would not even shoot a whole roll, even on a good day. They would be so careful about what they shot. I tended to, the more I got into it . . . I really got into shooting Sunset from the water, from my boogie board. I would go back . . . in and out, in and out. I think my world record was like 18 rolls of film in one day.

Q:

Q: Wow! 18 rolls! Really? That's amazing

A: Because when it was good, when the conditions are good there, you have to hang out...out there, for so long. The clouds, the rain, five minutes of sun, 30 seconds of sun . . .

Q: How would you change your exposure?

A: I could manually change the exposure. If it was good, I'd start ripping them off and just paddle in as fast as I could; Ya da-da-da-da-da, drink some water and get out there again. And then, I'd go back and forth, back and forth, which I really enjoyed. I'd just get these, just these epic photos!

Q: Did you have problems with your water-housings ever? Did they ever fail you?

A:

A: The problems I had with the water housing were; that in Hawaii, there's a lot of humidity. It's so moist and I'd get so excited. In my car . . . I'd put the camera housing there, place the camera inside and then put down the wing nuts and paddle out, and - you can be out there literally, for just five minutes, or half an hour, and it will start fogging up on you in the interior of the housing! That just used to flip me out!

Sometimes I would paddle way over in the channel and actually loosen all the lug nuts and lift the lid up and sit there until it cleared.

I came up with another technique where I would set the camera housing on my car and expose it to the hot sun for twenty minutes so it would not fog later, or use a hair dryer before I left the house.

And that gets into this whole thing of - in the early days there was no one teaching those things. Steve Wilking really helped me a lot. He was kind of a mentor, taught me a lot about commercial photography and surf photography. We would figure these things out; technical problems, like exposing Kodachrome-25. It had like a 1/2 stop latitude, and to freeze the action, in the water, you had to shoot at 1/500th of a second at f 5.6-8. Later on, I started using Velvia and all that (a faster color slide film). You know, I went out in the water at Haleiwa, Rocky Lefts, Sunset, Pipeline, I never went out at Waimea Bay. Waimea just freaked me out. I went out and photographed Avalanche once, from my raft, on a twenty-foot day, and I did a canoe ride out there with Dale Hope and Jeff Hornbaker was out there, also.

Q:

Q: I was going to ask you about that; how did you deal with your fear of being in big surf? How did you deal with that?

A: You know (long pause) . . . Hawaii was such a different animal. It would be like going from the earth to the moon. The whole atmosphere was different; the lighting was different, and the energy . . . Like literally a little shore break two-footer can just kick your ass! It can hit you in the knees and just knock you on your ass. Whereas in California, you just stand there and it goes by you and you kind of go, "Woo-hoo."

How did I deal with it? Sometimes I was so careful about looking at the swell direction, and waiting and watching the biggest set or sets, because Hawaii can trick you (or anywhere) you can go look and go, "Cool! It's like that, it's going to be easy." And you go home and get ready and meanwhile, you've missed the two-bomb sets because it's coming up, or something. So, you have to kind of watch it for twenty minutes or a half an hour, or a let a cycle of those long interval sets go through to see what's really happening.

But after a while, I got so good at it . . . It was different at different places. At Pipeline, I only went out when it was pure west, which meant it went from eight-foot to three-foot, which is a big barreling Pipe and it would go by like a big wedge and (Jeff now makes a sound effect like a turbine moving very fast and then slowing down) I would be in the channel kind of, and by the time it hit where I was in the channel (even though I was photographing the take-off which was 8 foot Hawaiian style) offshore with Rory (Russell) or Gerry (Lopez) or Jackie Dunn, it would go by so fast, like a triangle with a narrow tip and a large tip.

At Sunset Beach I got so comfortable I wouldn't go out if I saw it was closing-out initially. On my initial look I probably wouldn't go out, but I would often go out when it was big and getting bigger, and I just handled it. It wasn't . . .

Q:

Q: I mean, you didn't you prepare yourself in any psychological way? Create a state of mind to deal with it?

A: I never got scared. I learned not to talk to people and kind of be quiet, and keep watching the ocean, as I was getting ready. As soon as I started to talk to somebody, "Hey what," I would forget to do something with the equipment; not tighten a bolt down correctly or not put it on the right setting. I was so used to the ocean, like, paddling out at Black's on big bomb days, and getting stomped at Black's, you know, 150 times.

Q: Black's gets big, too.

A: The other thing is, in the back of my mind, I always knew, because of growing up and surfing pretty heavy waves in La Jolla, at Windansea & at Black's... there's one thing you always have to remember: YOU'RE NOT GOING TO DIE!

You can get stomped, even in the Islands, where you just go "OH FU*K!" and bail and press all the alarm buttons. You're not going to die. You're going to get swept up, turned upside down like in a washing machine and you're going to pop up, pretty much... I always knew that well.

Q: You felt that way, even in really big surf?

A: Big surf I'd freak out more, but even then, after you've been nailed, say, three or four or five times, you realize you're going to make it. I mean you can go through some pretty heavy scenarios, where you go a long way in the white water and it's hard to get a breath.

One time at Pipeline, I used to shoot Backdoor and in two different successions, I got bounced off the bottom. That really freaked me out. On one session, I was out there with Jack McCoy, and I got bounced off my butt really hard. There's this area where it's much shallower, where it's like a big shelf area, at Backdoor. I went "S--t! If that had been my head, I would have gotten F---ked . . .!"

Q: Is there anyway to define what makes a great surfing photograph? What elements need to be included in the photograph, in your opinion (in a broad sense) to make it great?

A:

A: (pause) Well... I have thought about that. There's a layer that's hard for me to punch out of . . . I . . . there are these parameters we've gone through in the history of surf photography . . . For example, the 'Stoner--Severson Era" was more moody, not necessarily perfectly shot; and then you had the era of the commercial Surf Magazine, in the 1980's where everything was perfectly shot, front lit, morning light, tack sharp, which is called " Larry Light" and a lot of that had to do with the printing of the magazines, which were so ill-printed, front lit, perfect lighting, bright and colorful (they printed better than the moody shots).

Q: Why did they call it "Larry Light"?

A:

A: Larry Light meant that you get up at dawn, when the sun is rising and go on a pier or a jetty or something, and you're looking at the surfer and he's front lit so all the colors come out. You can focus and he's sharp, so Larry Light is like morning light after a winter storm, where it's perfectly front-lit. Could be off a pier or a jetty, whatever, or off the beach...

So then, it went into an era where it went back again to kind of moody, when Rob Gilley became photo editor, they started using more moody-surfer-in-the-environment-type photos. It didn't matter if it was perfectly shot, if it had a mood to it.

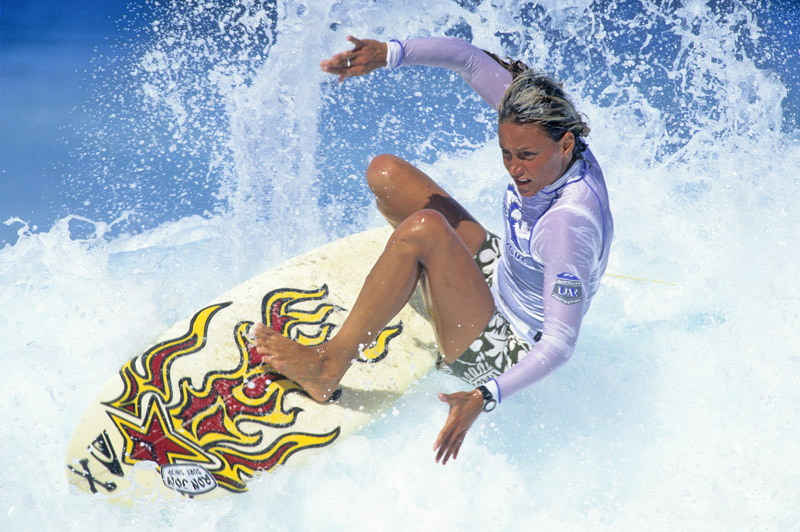

If you come back to the foundation, your audience is a core group of surfers. The bottom line for a great surf photo is; the surfer on a wave.

It's the perfect fantasy wave, and/or the surfer in his environment: sand dunes, palm trees, the majesty of nature: Fantasy wave, perfect conditions.You can get deeper than that, too. You can get into the body language of the surfer, to a core surfer like you and I, we could look at 150 surf photos, taken by five different guys, and you and I, based on that core surfer-outlook, would come up with five photos that we think are the "A's".

Then you could take somebody else who's looking at it from this, say, perfect commercial sense: they would pick five different ones!

So there are different audiences. Our audience is this core group that can tell the difference in everything. They can tell, by the body language, who the surfer is.

Q:

Q: Were you consciously aware when you were shooting Rory (Russell), or especially Gerry (Lopez), or some of the other major surfers in Hawaii, were you consciously aware that you were making an effort to get photographs that truly defined their greatness or their individual style? Was it something you thought about?

A: In that time there were so few guys on the beach, it was beautiful.

Q: So you're talking about the 1970's?

A: Yes the 70's, a little of the 80's also, but the 70's were more romantic. There were only a handful of us photographers. I'd go check it out and go, "All right! West swell...I'm down there!" And depending on my mood, I'd have, let's say, the land lens, and I set up at an angle, because I knew Gerry and Rory and Jackie Dunn and those guys. They had rented a house there and it was a perfect front-lit sunny morning and here's come Jerry, he comes walking down the beach, and YEAH! I'm the only photographer around, and I'm photographing the greatest surfer in the world, and the show is about to begin, it was so exciting. This was before the Aussies came and all that.

In those days, there was a time when there were a handful of us; like, it could be an hour before another photographer showed up. It could be five minutes, but that little window of time, where you knew you were getting "it." You'd get so stoked because you knew you had captured something unique, that no one else had.

In that day you could build those times up, like, "Oh My God! I shot Rocky Point and all those guys were out, and no one else was there!" What you see now-a-days is that everybody's there. Every spot is filled, there's guys in the trees . . . up in the Da Da da Da Daaa! It's like a maggot scene, as Aaron Chang once said.

Q:

Q: It is like a circus. Is there something about your own work that you think defines your unique eye, in relationship to other surfing photographers? Past and present, is there something you see in your own work, something special?

A: Early on, say in the 70's, what I was known for (and I think it goes back personally to that DNA-inheritance thing) is that I saw . . . I did some of the classic line-ups of the 70's and I had a cover. I had other ones that were classics; I had something going on... so that I could get that "scene" that I was talking about.

Q: Something deeper?

A: That scene I was talking about, where the palms are draping, there's the beach and the Pukka-Picker lady with a hat on and there's Gerry, Jackie and Rory, armed with BOLT surfboards waiting to paddle out, and there's the perfect V-shaped peak going off in the ocean, and for some reason in surf photography that wasn't going on so much then. So those were some of my "big deal" photos.

The other thing I was known for was being able to manually focus the 1000mm telephoto lens really well, which was really hard to do. It was like looking through a hazy coke bottle all day long. And the other quality I had . . .

Q:

Q: You have absolutely no depth of field with a 1000mm lens.

A: It was really difficult, and I spent hours on the beach. I put in these hours; I'd go hang on the beach. I was always searching for who was out and where, and driving around. I worked really freakin' hard at it.

Q: Well, it shows!

A: A lot of guys would leave the beach, and I'd just go back up in the bushes, in the shade, hang out, talk to people and have fun.

Q: Was the magazine covering your expenses, more or less, then? Could you live off that?

A:

A: Yes but initially, it was poverty scale. I was in my 20's. What was so interesting though, at a certain point in time, when I had a lot of photos of Gerry Lopez published on the cover (posters and this and that) in my world of surfer's on the North Shore, no one had money. So they all thought I was rich, like, "OMG! Divine's got another poster, another cover," so I'm going, "Hey you guys, give me a break!" My rent was $75.00. I would buy food, I'd hang out on the North Shore and I would still run out of money. By 1976 I was put on a $500.00 a month retainer.

Q: Did the locals, the Hawaiians, welcome you in the beginning? Did you have to go through the "You're-a-haole-from-California" thing, and prove yourself? That can get intense and dangerous, if you're not accepted, as you know.

A: I never went through that because in my first year there I was immediately let through "the door." I was Surfer Magazine. "Steve Pezman sent me from Surfer Magazine," so the doors were just wide open for me. It was still an insider-world; if you were the classic haole, yeah, you would get hassled. But I was immediately hanging out with major locals: Tiger Espere, Buddy Boy, Callahan, Garner, Jim Turner, Barry K, Sam and Owl Chapman. I was immediately hanging out with those guys. They were enamored because I was a shy kid and I never realized this until later: I had this presence that they knew . . . "Oops, Surfer Magazine!" - as soon as I walked onto the beach.

Q: Do you think, in a way, you inspired them to surf better? Knowing that you were there, photographing them?

A: Probably. I don't realize that myself, but I've been told a million times, everybody gets hyped-up in the water when you set up the lens. That is true, up to a point.

Q:

Q: How important was the light you were photographing in? Was it something you really had to think about? How did you choose a location on the beach to shoot from? What were your criteria?

A: Here I go again! I think it's the DNA. It's the inherited thing of forming up lines. My dad was an architect. So as I was roaming around, I would always think of where to set up to get a side angle and a good composition. Would I be looking into it (the wave) or maybe even straight on? I would always be working on those angles, looking ahead for the results. In those days, it took a while to get your film processed and back. You would look at the results from different angles and adjust. I would never just plop down and stay in one spot all day long. I'd shoot at a spot for an hour or so, depending on the surf, and then move around the beach.

I think, the actual process of forming your vision, especially in a viewfinder, is that there is a lot of geometry that is so sophisticated that I can't even begin to explain it...

Q: And what's not in the frame; what you're not going to show?

A: Yeah, exactly! I had that [instinct] inside of me. I would walk around with special goggles on; "Jeff Divine Goggles," looking at scenes totally differently than other surf photographers, like Art Brewer, Steve Wilkens, or Bernie Baker. Those other guys see it totally differently than I see it.

That's when I realized the beauty of what I'm saying. Early on I realized that I was wound up in jealousy and, "Oh MY GOD! These guys are shooting the same angle that I am." Then I realized, "F---k it! My photos are going to be different than theirs, no matter what!

Years later, in 1981, when I came back from Hawaii to be photo editor, I was looking at everybody else's photos. I realized it was absolutely true. Every guy has a completely different take on the same morning at Pipeline. That was a big deal, to realize that. It was a big leap forward for me. "Hey, you know, my photos are my photos. I am what I am. Like Popeye - bring it on!" It doesn't matter.

Because surf photography is such a fluid thing; it's the weather conditions, who is surfing, the swell direction and the lighting . . . It's this fluid thing that's changing. You can have a three-hour stretch of perfection or a 45-minute stretch of perfection (for photography) like you caught something, something that's really valuable. In studio photography there's one person in the studio, adjusting the lighting and so on. You don't have any competition from any other photographers in the room. You're shooting a product, or a movie star.

In surf photography you compete because there are always other photographers there, shooting alongside you during that special hour.

Q:

Q: Exactly, I agree... the precise moment you choose to release the camera's shutter, right then, in that split second there are significant and subtle things that make it a "Jeff Divine photograph," rather than someone else's. And there is a consistency of excellence throughout your career. Is there something you see in your work that's been consistent from the beginning? Even going back to the La Jolla days?A I think that my thing was being a pretty good surfer. So I had an understanding of what the surfer was going to do, knowing those moments which were a little more photogenic, as opposed to dorky-looking shots. Through my photography, I'm speaking to a core audience.

Q: Your knowledge, then, of surfing?

A: Yes my knowledge is one thing. I hate this because it sounds like a cliché, but hard work, hanging out, and that body chemistry-outlook that made it all unique. Because other guys would flame out, or get tired, or they were lazy, or they just weren't that into it.

Q: What about when you were in the water though. Were there other water photographer's around you?

A: At first, myself and the other guys would get pissed, like, "Who's this guy? Oh s-t! What?"

Q:

Q: Would it get dangerous when you both wanted to be in the same position, at the same place? At the same time?

A: No, no. There's a lot of room out there, a lot of playing field. We used to shoot the inside bowl at Sunset. That was the "Golden Nugget." That was hard; you had to hang and hang and hang, and the current kept taking you out, but you kept adjusting. In the 1980's it started to get a lot more crowded in the water. There could be eight or ten guys out shooting water shots. If there were too many guys you'd say, "F---k It," and go out into the middle zone where you could be by yourself.

Q: Where there times that you would ask yourself whether to load color or black & white film? And if you did shoot black & white, what would be the reason?

A: Early on I did shoot a lot of black & white because Surfer magazine wanted us to. Only about a third of Surfer magazine was in color at the time. But in the 1980's it went all color. We would just convert from color to black & white. We had a full-fledged darkroom at Surfer magazine, all the way through the late 80's. I like working in the darkroom, as long as it's my own work. I couldn't imagine processing every body else's stuff.

Q: Has the client-base changed over the years? Can surf photographers get assignments or commercial commissions from big surf companies like O'Neil or Quicksilver, for the purpose of hiring them for print & video work?

A: A couple of things have happened in the recent past. The bigger companies have realized it behooves them to have a guy on retainer, a young guy on a salary, to run around with their surf team. He's got to be approximately the same age because then he can relate to them, and party with them or whatever, and still get their photos. They can use those photos worldwide, and not have to buy them piece-by-piece. The problem is that they don't get everything that goes on, because all these companies have these highly paid team members (surfer's) making huge amounts of money. They literally assign a videographer and a still guy to be their buddies!

Q: When you were doing your surf photography in the Islands, you probably didn't imagine that your work would be shown in really fine art galleries and museums. Was that much of a surprise to you, that eventually your work would be considered art, serious art? When you exhibited at the M&B gallery in West Hollywood and made significant sales, was that like frosting on the cake for you?

A: When I first started to realize that I was getting something special was when . . . Part of it was when I was connected at the hip to Surfer magazine. Early on, it would open doors. For instance, I would get a cover on a Jan & Dean album, especially after I moved back (from Hawaii) and was in the office of Surfer I'd get an American Express ad of an empty Waimea shore break photo.

Q: How did they know about them?

A: I'd advertise through the "Work Book" or they would call me. When people started calling my work "art," my first reaction was, "Really?" I didn't feel like I was doing anything special.

Q: You don't feel that way now, do you?

A: What I've learned is that if I edit through my stuff and pick out what I like, usually that's the finer work. One thing that made me feel really good about my work was when Craig Stecyk saw a book I did on my work from the 70's. It had to do with people and the culture, not just man on wave, but all this other stuff.

Even today I'm not a "people person." It's hard for me to take photos of people. I used to kind of spy on them with a 135mm lens or something. Stecyk pointed out that my work was different. I was like a fly on the wall and I was in with this "in" crowd of surfers on the North Shore where they didn't just allow a random guy to really hang out. They would tell him to "F--k off, or they would be rude, or turn their back on the guy. But I was just hanging with them and absorbing it. It's kind of like what you guys did with your street stuff, like the work you did on "Dog Town". You were friends with those guys. You talked about when they were bummed out with their chick, or they didn't have any money. You absorbed their life and therefore, when you were hanging with them, photographing them, it didn't seem like you were capturing art. I see it now.

Now... in today's world, there would be some famous photographer who's assigned to come and shoot and meet the surfers. In my day, that didn't happen. I was assigned to hang out with them through Surfer magazine, but I was one of them. I was an Indian so to speak. I could run through different tribes, whether it was Santa Barbara or the North Shore. I was accepted and never got hassled by anybody on the North Shore. The Hawaiians used to . . . I'd set up my 1000mm lens and a car would pull up and they'd be drinking and I'd go "Oh s--t...Oh s-t!" I had long hair; I had more of a hapa haoli look. I wasn't blonde hair, blue eyes; I had dark features. But in my brain it's going "Emergency! Emergency!" Drunk local guys . . . Oh S-t!" I remember one time out at Sunset, I'm out in the boonies kind of in the bushes, and a drunken guy comes up and says "Hey Bra'! Don't worry! We're goin' ta play music for you." They gather around my 1000mm lens and me. I'm shooting Barry Kanaiaupuni, Tiger Espere, Eddie Aikau, Ben Aipa and I'm shooting sequences with the Nikon motor drive. They were drinking beers and playing Hawaiian music, asking who's on that wave. "Who's that?" Then they left. "Hey Bra'! Have a good time!" I was stoked. I was so accepted.

Q: What do you think it is about the medium of photography that makes it special? What is it about photography that's identifiably different from everything else in the visual arts?

A: It's so hard to pinpoint. But as time goes on I realize, especially with what I do, which is a kind of nature photography (the surfer and his world) it changes so quickly that what I'm capturing is something unique; a certain moment in time that will never happen again. You cannot recreate that, especially in surf photography. For example: Santa Ana offshore winds, a certain swell, a certain swell direction, a certain guy out in the water, and certain cars in the foreground - it can literally be that window that you captured. In surf photography it could be the four photos you took before the wind switched to onshore or before the guy walked out of the frame.

My famous story, one I always tell, is that I lived right at Pipeline, front row (in this little one-bedroom that Kelly Slater stays in now) and we were all into rainbows, bragging about who got the best rainbow photo, over two or three months. One morning around 9AM, I look out and there's this full arc rainbow. I think, "Holy S--t!" I grab my camera, put in a roll of film, run down on the beach, in a misty rain . . . a rainbow can last seconds or a minute. I shot a roll of film, 36 pictures, and one of the frames was right on!... the rainbow, the surfers on the beach, a wave breaking in the background (a good wave) and that's it: that little window of time to get a really great photograph.

Q: What would your advice be to a young surf photographer today? I ask this question because at Samy's Camera, we have many young photographers who hope to one day become professionals and pursue a serious career in photography. What would you tell them?

A: (Heavy sigh) Oh, God!

Q:

Q: What would you say to them under today's circumstances?

A: I'd say that's it's difficult; its like wanting to be a pro tennis player. You get all these people from all over the United States who are really, really good at tennis, and you want to be one of the top guys.

I would say start out by educating yourself, and through that process you'll realize whether you have got the "chops" or not. This could be any type of photography actually, but surf photography specifically. Number one: you have to be an ocean person. In today's surf photography, a lot of body boarders are the greatest surf photographers because they are used to kicking around in the impact zone on a body board at Pipe, Backdoor, you name it, Windansea, wherever. They're used to getting pounded, and popping right up. "Oh, well. Ha, ha, ha, I got pounded." They know a bunch of techniques for duck diving in dangerous conditions.

Educate yourself also about filming; a lot of the new cameras have a high-definition video option. It's a whole other thing and today it runs hand-in-hand with photography. Get really computer literate and follow your intuition. Don't worry about all the other guys. Go for it!

Don't worry about money because you're not going to make much, if any. You're going to get rejected and all those things. You need to build up a basic wall of knowledge about video and digital still photography, la.da.da.da.da, film processing, computer techniques . . .so on...

Also, having skills; like survival swimming ability at dangerous shallow breaks: ocean knowledge is mandatory.

Q: Do you now, I mean being the photo editor at The Surfer's Journal (a world class surfing magazine), do you miss the days where you can hang out, be on the beach and pull out the long telephoto lens? Or go into the surf with your water housing the way you used to? Photographing mega surf stars getting in and out of the shorebreak? A Yes...I really miss it..

Q: You still do it though ...don't you? A I still do it, but in a weird way...I'm so wound up in the computer all day long...photo editing for the magazine...wheeling and dealing my own work, emailing and all that, but the neatest thing is that I shoot my son, my son's like a great surfer, Taylor. He drags me out and I shoot him.

Q: Cool...photographing your own son...that's great.

A: The other thing I've done is, I've donated these photo sessions with Jeff Divine, to Surf Aide International, which helps kids in the Mentawai islands, which is where we go on these yachts... and we never help the kids, and the tribes, on these isolated islands. They get Malaria, and all these horrible things go on, so I donated a Jeff Divine shoot for that; which helps raise money in order to help these people...

I still love going out on the Jetty's and shooting, getting out there, shooting young surfer's, plugging me back in...I just love it...so I try to do that more...

AF: Jeff, I want to sincerely thank you for doing this interview and sharing many of your memories, and insight about your work today. It will be greatly appreciated by the many photographers who are huge fans of your work, including myself. We will have a much deeper understanding about your process as a fine photographer. ALOHA

Surfing is one of the oldest and most enjoyed sports on our planet. Waves are like liquid sculpture, they move through the ocean with ethereal beauty. The art of wave riding (and for many surfers it becomes a type of religious dedication) is a blending of physical talent and personal expression. This is coupled with the reverence for the magnificent power of nature, the ocean in particular.

Jeff Divine is considered one of the finest surfing photographers ever; and that includes the entire history of surf photography. He has produced some of the most inspiring and classic surfing pictures of all time. Jeff Divine is not only a master surf photographer; he is a master photographer. Period.

Divine has dedicated over 40 years to this specific genre of photography. His photographs connect the spiritual powers of nature, a celebration of life and his own deep love of surfing in all of its varied characteristics and with all that encompasses. His work is unequaled. He has numerous books out and his work has been published internationally. His work is exhibited at fine museums and art galleries.

Q: How did you get started in photography? What was your very first camera? How old were you when you first went into a darkroom? (Jeff is shooting portraits of me while I ask him questions.)

A: In a nutshell, here is a little back round: Before I ever got a camera, my mom was an artist. She went to Mills (College for Women in San Francisco) and she majored in music. I grew up in the art world of La Jolla, California.

My mother was a founder of the La Jolla Museum of Art; she held fundraisers in our backyard. My father was an architect-artist who went to Berkley and built a modernist home in La Jolla Shores. My grandmother was also an artist. She painted watercolors of flowers and hung out in the artist's colony at Balboa Park where she exhibited her work. So, I have that [art] background.

I always like to tell people that I think photography is either in your DNA or it's not in your DNA. It's like a "body chemistry" thing that allows you to form things in this little frame. It's something you either have or you don't. There are other qualities, too, like your personality, what attracts you to different things, and how you interact with people . . . The building blocks, in my case, were "Who Were Your Parents," and my parents all happened to be artists. I kind of lucked out in that sense.

Surfing is one of the oldest and most enjoyed sports on our planet. Waves are like liquid sculpture, they move through the ocean with ethereal beauty. The art of wave riding (and for many surfers it becomes a type of religious dedication) is a blending of physical talent and personal expression. This is coupled with the reverence for the magnificent power of nature, the ocean in particular.

Jeff Divine is considered one of the finest surfing photographers ever; and that includes the entire history of surf photography. He has produced some of the most inspiring and classic surfing pictures of all time. Jeff Divine is not only a master surf photographer; he is a master photographer. Period.

Divine has dedicated over 40 years to this specific genre of photography. His photographs connect the spiritual powers of nature, a celebration of life and his own deep love of surfing in all of its varied characteristics and with all that encompasses. His work is unequaled. He has numerous books out and his work has been published internationally. His work is exhibited at fine museums and art galleries.

Q: How did you get started in photography? What was your very first camera? How old were you when you first went into a darkroom? (Jeff is shooting portraits of me while I ask him questions.)

A: In a nutshell, here is a little back round: Before I ever got a camera, my mom was an artist. She went to Mills (College for Women in San Francisco) and she majored in music. I grew up in the art world of La Jolla, California.

My mother was a founder of the La Jolla Museum of Art; she held fundraisers in our backyard. My father was an architect-artist who went to Berkley and built a modernist home in La Jolla Shores. My grandmother was also an artist. She painted watercolors of flowers and hung out in the artist's colony at Balboa Park where she exhibited her work. So, I have that [art] background.

I always like to tell people that I think photography is either in your DNA or it's not in your DNA. It's like a "body chemistry" thing that allows you to form things in this little frame. It's something you either have or you don't. There are other qualities, too, like your personality, what attracts you to different things, and how you interact with people . . . The building blocks, in my case, were "Who Were Your Parents," and my parents all happened to be artists. I kind of lucked out in that sense.

Q: How old were you when you first started taking pictures?

A: I was 16. I worked at John Cole's Bookstore in La Jolla and some friends of mine were taking surf photos. They would make black & white prints, we'd be standing around, putting our boards away on the racks near our neighbor's house and they would pull up and have these prints with them and say, " Look! I just shot this of Barry Kanaiaupuni at Windansea or, "Here's (David) Nuuhiwa! He's this incredible guy from Hawaii, and here he is, riding the nose!"

Q: How old were you when you first started taking pictures?

A: I was 16. I worked at John Cole's Bookstore in La Jolla and some friends of mine were taking surf photos. They would make black & white prints, we'd be standing around, putting our boards away on the racks near our neighbor's house and they would pull up and have these prints with them and say, " Look! I just shot this of Barry Kanaiaupuni at Windansea or, "Here's (David) Nuuhiwa! He's this incredible guy from Hawaii, and here he is, riding the nose!"

For some reason I was so attracted to those 8x10 black & whites! So, I got a camera with the money I earned at the bookstore, and my grandmother subsidized me. The funny thing is that I didn't start right off shooting surf photos. I started shooting like . . . I was attracted to light and reflection, composing lines and other things besides surfing. One day I see a beautiful sunset. I go running up to the Marine Room (restaurant with a view of the La Jolla Cove) and start shooting photos and I align the agave plant in the foreground with those old Portuguese tuna boats that were in La Jolla cove . . . and BOOM! I got a cover of San Diego Magazine! I was self-taught. I had to figure it out. It was hard to learn how to expose Kodachrome-25 color slide film.

For some reason I was so attracted to those 8x10 black & whites! So, I got a camera with the money I earned at the bookstore, and my grandmother subsidized me. The funny thing is that I didn't start right off shooting surf photos. I started shooting like . . . I was attracted to light and reflection, composing lines and other things besides surfing. One day I see a beautiful sunset. I go running up to the Marine Room (restaurant with a view of the La Jolla Cove) and start shooting photos and I align the agave plant in the foreground with those old Portuguese tuna boats that were in La Jolla cove . . . and BOOM! I got a cover of San Diego Magazine! I was self-taught. I had to figure it out. It was hard to learn how to expose Kodachrome-25 color slide film.

Q: Were you shooting mostly color?

A: Yes, color; color right away. I started going at it all by myself. There was no mentor, nobody else.

Q: Did you read books?

A: The only thing I read at that point in time was the Life (Magazine) series of books on photography, which gave me a context. I was like the "happy-wappy" kid from down south to guys up here at Surfer Magazine and Dana Point. So, by 1967, I started giving them my photos of perfect Black's. Or, because I'd wait before I'd shoot (it might take awhile to shoot one roll of 36 photos, all of them) I would always surf, too. Then I would shoot. Or when I was burned out, I would go shoot. But I always surfed first.

Q: Were you shooting mostly color?

A: Yes, color; color right away. I started going at it all by myself. There was no mentor, nobody else.

Q: Did you read books?

A: The only thing I read at that point in time was the Life (Magazine) series of books on photography, which gave me a context. I was like the "happy-wappy" kid from down south to guys up here at Surfer Magazine and Dana Point. So, by 1967, I started giving them my photos of perfect Black's. Or, because I'd wait before I'd shoot (it might take awhile to shoot one roll of 36 photos, all of them) I would always surf, too. Then I would shoot. Or when I was burned out, I would go shoot. But I always surfed first.

Q: How do you deal with that now?

A: Now I tend to just shoot. It's a long story because it's evolved. I mean I've been doing it for 45 years. A big middle chunk of my career was becoming more professional about taking surf photos rather than surfing, where you can hurt your ankle or your knee, or get too tired. And then, you can't focus.

Q: How do you deal with that now?

A: Now I tend to just shoot. It's a long story because it's evolved. I mean I've been doing it for 45 years. A big middle chunk of my career was becoming more professional about taking surf photos rather than surfing, where you can hurt your ankle or your knee, or get too tired. And then, you can't focus.  As I became more professional over the years, I learned that you've got to focus on taking pictures.

Then, as pro-surfing evolved; the pro-surfers didn't really want me to be surfing with them. They want me to be taking their photos because that means money to them.

Q: So, when did you get your first underwater housing?

As I became more professional over the years, I learned that you've got to focus on taking pictures.

Then, as pro-surfing evolved; the pro-surfers didn't really want me to be surfing with them. They want me to be taking their photos because that means money to them.

Q: So, when did you get your first underwater housing?

A: What happened was I started coming up to Surfer (Magazine) and they liked me. Art Brewer and Ron Stoner were shooting for Surfer. And John Severson was around, but he was starting to bail out to Maui. Stoner was melting down mentally and I was positive and "stoked," as they say; all of a sudden the staff gives me some photo equipment to use, and they suggested I get a water housing for myself, which I did, from Scott Priess.

I started shooting Windansea and Big Rock, etc.

Q: So this was 'way before digital; you were shooting film?

A: Yes. This might have been in 1969 or 1970, when I got my first water housing.

Q: Were you swimming with fins?

A: What happened was I started coming up to Surfer (Magazine) and they liked me. Art Brewer and Ron Stoner were shooting for Surfer. And John Severson was around, but he was starting to bail out to Maui. Stoner was melting down mentally and I was positive and "stoked," as they say; all of a sudden the staff gives me some photo equipment to use, and they suggested I get a water housing for myself, which I did, from Scott Priess.

I started shooting Windansea and Big Rock, etc.

Q: So this was 'way before digital; you were shooting film?

A: Yes. This might have been in 1969 or 1970, when I got my first water housing.

Q: Were you swimming with fins?

A: I had a converse raft with Churchill UDT fins and no leash on the raft. I'd go out to Windansea, Big Rock, La Jolla Shores, which were difficult from the water . . . Go out at Black's . . . Some of the time, I'd swim out. I had to use a manual focus-135mm lens (which is really hard to focus; try it sometime!). The surfer is speeding at you, and the closer they get the harder it gets. You're moving with this and that and worried that the wave is going to hit you. It was very difficult.

A: I had a converse raft with Churchill UDT fins and no leash on the raft. I'd go out to Windansea, Big Rock, La Jolla Shores, which were difficult from the water . . . Go out at Black's . . . Some of the time, I'd swim out. I had to use a manual focus-135mm lens (which is really hard to focus; try it sometime!). The surfer is speeding at you, and the closer they get the harder it gets. You're moving with this and that and worried that the wave is going to hit you. It was very difficult.

Then, I transferred that knowledge and moved to Hawaii in 1971. I was kind of like a water child, growing up near the beach in La Jolla Shores, so it wasn't that hard of a transition to go and do the same thing in Hawaii. But the funny thing was that, doing water shots in Hawaii, I was alone.

Today, you can sit in your car and watch what the other photographers do because there are hoards of them. In my day, I'd sit in my car and get scared because there was the shore break. There's the peak out at Sunset and it's 10-foot feathering offshore. All the experienced surfers look like He-Men. They know what they're doing and they're walking by you all confident and everything, and I'm, like, s---ting myself (laughter)!

Hawaii is so much more powerful than California. We live in a wimpy swirl pond compared to Hawaii - the power and the rip tides. All that energy of the ocean is so different! I'd get my gear together and go stand at the shore break at Sunset going, "Oh s-t! Oh s--t!" You have to time yourself to go out and wait for the lull or you can get completely screwed up in the shore break. It can be very dangerous. It doesn't look that bad, but it can be really rowdy. Once you get over that little -fifteen -twenty-foot zone, its deep water with a big rip through it. You just kick as hard as you can, and the rip drags you over to Kammieland. Then you just head straight across to the peak at Sunset and station yourself, depending on whether you want to shoot the inside or the middle peak, the swell; and that's were it becomes so exciting! Being a water person, I'm not terrified, just . . . It's such a thrill! Because it's so intense, these big walls and offshore! And these guys are out...

Then, I transferred that knowledge and moved to Hawaii in 1971. I was kind of like a water child, growing up near the beach in La Jolla Shores, so it wasn't that hard of a transition to go and do the same thing in Hawaii. But the funny thing was that, doing water shots in Hawaii, I was alone.

Today, you can sit in your car and watch what the other photographers do because there are hoards of them. In my day, I'd sit in my car and get scared because there was the shore break. There's the peak out at Sunset and it's 10-foot feathering offshore. All the experienced surfers look like He-Men. They know what they're doing and they're walking by you all confident and everything, and I'm, like, s---ting myself (laughter)!

Hawaii is so much more powerful than California. We live in a wimpy swirl pond compared to Hawaii - the power and the rip tides. All that energy of the ocean is so different! I'd get my gear together and go stand at the shore break at Sunset going, "Oh s-t! Oh s--t!" You have to time yourself to go out and wait for the lull or you can get completely screwed up in the shore break. It can be very dangerous. It doesn't look that bad, but it can be really rowdy. Once you get over that little -fifteen -twenty-foot zone, its deep water with a big rip through it. You just kick as hard as you can, and the rip drags you over to Kammieland. Then you just head straight across to the peak at Sunset and station yourself, depending on whether you want to shoot the inside or the middle peak, the swell; and that's were it becomes so exciting! Being a water person, I'm not terrified, just . . . It's such a thrill! Because it's so intense, these big walls and offshore! And these guys are out...

Q: Would you be in the impact zone? Or close to the impact zone?

A: No, no! That was the thing! With the 135mm lens the whole thing about surf photography is to avoid the impact zone. Being a surfer, you know, all those years your whole thing with surfing is avoiding the impact zone, negotiating the inside reef, and the mid-reef and lining up with the trees on the hill because if you get caught you are screwed...

So you're always negotiating. You're always kicking hard and paddling hard . . . like your housing is in one hand, with one arm, and you're kicking as hard as you can, and the raft is going, "OH NO! OH NO!" (Jeff makes all kinds of funny ocean sounds) "BOOM!" And I go over the falls and take a serious wipeout . . . And then I ground myself again. I see a set come in, and, depending on who it is, what surfer is taking off, I wipe the front of my plexi-front port (a plexi glass cylinder with a water tight plex-face that the lens fits into) making sure there are no water drops on it and station myself; "Manual focus! Manual focus! Shoot!!" It's so many hours out there.

Q: Would you be in the impact zone? Or close to the impact zone?

A: No, no! That was the thing! With the 135mm lens the whole thing about surf photography is to avoid the impact zone. Being a surfer, you know, all those years your whole thing with surfing is avoiding the impact zone, negotiating the inside reef, and the mid-reef and lining up with the trees on the hill because if you get caught you are screwed...

So you're always negotiating. You're always kicking hard and paddling hard . . . like your housing is in one hand, with one arm, and you're kicking as hard as you can, and the raft is going, "OH NO! OH NO!" (Jeff makes all kinds of funny ocean sounds) "BOOM!" And I go over the falls and take a serious wipeout . . . And then I ground myself again. I see a set come in, and, depending on who it is, what surfer is taking off, I wipe the front of my plexi-front port (a plexi glass cylinder with a water tight plex-face that the lens fits into) making sure there are no water drops on it and station myself; "Manual focus! Manual focus! Shoot!!" It's so many hours out there.

Q: Was it difficult though with only 36 pictures? Did you have to try to pace yourself at all?

A: Yes, I'd pick and choose who I might shoot, then I'd pick and choose the sets and the direction of the swell. That was really important, because certain directions you know aren't going to pitch out; other ones you know are going to have a nice wall or pitch out, so there was a whole science going on in my head, as a surfer, because I know the ocean.

I'd analyze it every time a set would come in: "Da, da, da . . . Where's Hakman? Where's so and so?" As soon as I'd see my target guy paddling, whoever it might be, Shaun or Rabbit or BK or Ian Cairns or any of those guys, and get ready and carefully pick my shots, anticipate the moment.

What blew my mind, I got my first digital housing a few years ago and I went on a trip to Indo and I say "let freedom ring"! It's like I'm shooting my feet, the sky, (laughter) my friend's paddling by . . . no problem... It was fabulous. I'd just put the throttle down and, with a wide-angle lens, from when the guy takes off - until he is all the way past me, I could shoot.

There were some guys, in the days of one roll of film with 36 shots, that would not even shoot a whole roll, even on a good day. They would be so careful about what they shot. I tended to, the more I got into it . . . I really got into shooting Sunset from the water, from my boogie board. I would go back . . . in and out, in and out. I think my world record was like 18 rolls of film in one day.

Q: Was it difficult though with only 36 pictures? Did you have to try to pace yourself at all?

A: Yes, I'd pick and choose who I might shoot, then I'd pick and choose the sets and the direction of the swell. That was really important, because certain directions you know aren't going to pitch out; other ones you know are going to have a nice wall or pitch out, so there was a whole science going on in my head, as a surfer, because I know the ocean.

I'd analyze it every time a set would come in: "Da, da, da . . . Where's Hakman? Where's so and so?" As soon as I'd see my target guy paddling, whoever it might be, Shaun or Rabbit or BK or Ian Cairns or any of those guys, and get ready and carefully pick my shots, anticipate the moment.

What blew my mind, I got my first digital housing a few years ago and I went on a trip to Indo and I say "let freedom ring"! It's like I'm shooting my feet, the sky, (laughter) my friend's paddling by . . . no problem... It was fabulous. I'd just put the throttle down and, with a wide-angle lens, from when the guy takes off - until he is all the way past me, I could shoot.

There were some guys, in the days of one roll of film with 36 shots, that would not even shoot a whole roll, even on a good day. They would be so careful about what they shot. I tended to, the more I got into it . . . I really got into shooting Sunset from the water, from my boogie board. I would go back . . . in and out, in and out. I think my world record was like 18 rolls of film in one day.

Q: Wow! 18 rolls! Really? That's amazing

A: Because when it was good, when the conditions are good there, you have to hang out...out there, for so long. The clouds, the rain, five minutes of sun, 30 seconds of sun . . .

Q: How would you change your exposure? A: I could manually change the exposure. If it was good, I'd start ripping them off and just paddle in as fast as I could; Ya da-da-da-da-da, drink some water and get out there again. And then, I'd go back and forth, back and forth, which I really enjoyed. I'd just get these, just these epic photos!

Q: Did you have problems with your water-housings ever? Did they ever fail you?

Q: Wow! 18 rolls! Really? That's amazing

A: Because when it was good, when the conditions are good there, you have to hang out...out there, for so long. The clouds, the rain, five minutes of sun, 30 seconds of sun . . .

Q: How would you change your exposure? A: I could manually change the exposure. If it was good, I'd start ripping them off and just paddle in as fast as I could; Ya da-da-da-da-da, drink some water and get out there again. And then, I'd go back and forth, back and forth, which I really enjoyed. I'd just get these, just these epic photos!

Q: Did you have problems with your water-housings ever? Did they ever fail you?

A: The problems I had with the water housing were; that in Hawaii, there's a lot of humidity. It's so moist and I'd get so excited. In my car . . . I'd put the camera housing there, place the camera inside and then put down the wing nuts and paddle out, and - you can be out there literally, for just five minutes, or half an hour, and it will start fogging up on you in the interior of the housing! That just used to flip me out!

Sometimes I would paddle way over in the channel and actually loosen all the lug nuts and lift the lid up and sit there until it cleared.

I came up with another technique where I would set the camera housing on my car and expose it to the hot sun for twenty minutes so it would not fog later, or use a hair dryer before I left the house.

A: The problems I had with the water housing were; that in Hawaii, there's a lot of humidity. It's so moist and I'd get so excited. In my car . . . I'd put the camera housing there, place the camera inside and then put down the wing nuts and paddle out, and - you can be out there literally, for just five minutes, or half an hour, and it will start fogging up on you in the interior of the housing! That just used to flip me out!

Sometimes I would paddle way over in the channel and actually loosen all the lug nuts and lift the lid up and sit there until it cleared.

I came up with another technique where I would set the camera housing on my car and expose it to the hot sun for twenty minutes so it would not fog later, or use a hair dryer before I left the house.

And that gets into this whole thing of - in the early days there was no one teaching those things. Steve Wilking really helped me a lot. He was kind of a mentor, taught me a lot about commercial photography and surf photography. We would figure these things out; technical problems, like exposing Kodachrome-25. It had like a 1/2 stop latitude, and to freeze the action, in the water, you had to shoot at 1/500th of a second at f 5.6-8. Later on, I started using Velvia and all that (a faster color slide film). You know, I went out in the water at Haleiwa, Rocky Lefts, Sunset, Pipeline, I never went out at Waimea Bay. Waimea just freaked me out. I went out and photographed Avalanche once, from my raft, on a twenty-foot day, and I did a canoe ride out there with Dale Hope and Jeff Hornbaker was out there, also.

And that gets into this whole thing of - in the early days there was no one teaching those things. Steve Wilking really helped me a lot. He was kind of a mentor, taught me a lot about commercial photography and surf photography. We would figure these things out; technical problems, like exposing Kodachrome-25. It had like a 1/2 stop latitude, and to freeze the action, in the water, you had to shoot at 1/500th of a second at f 5.6-8. Later on, I started using Velvia and all that (a faster color slide film). You know, I went out in the water at Haleiwa, Rocky Lefts, Sunset, Pipeline, I never went out at Waimea Bay. Waimea just freaked me out. I went out and photographed Avalanche once, from my raft, on a twenty-foot day, and I did a canoe ride out there with Dale Hope and Jeff Hornbaker was out there, also.

Q: I was going to ask you about that; how did you deal with your fear of being in big surf? How did you deal with that? A: You know (long pause) . . . Hawaii was such a different animal. It would be like going from the earth to the moon. The whole atmosphere was different; the lighting was different, and the energy . . . Like literally a little shore break two-footer can just kick your ass! It can hit you in the knees and just knock you on your ass. Whereas in California, you just stand there and it goes by you and you kind of go, "Woo-hoo."

How did I deal with it? Sometimes I was so careful about looking at the swell direction, and waiting and watching the biggest set or sets, because Hawaii can trick you (or anywhere) you can go look and go, "Cool! It's like that, it's going to be easy." And you go home and get ready and meanwhile, you've missed the two-bomb sets because it's coming up, or something. So, you have to kind of watch it for twenty minutes or a half an hour, or a let a cycle of those long interval sets go through to see what's really happening.

Q: I was going to ask you about that; how did you deal with your fear of being in big surf? How did you deal with that? A: You know (long pause) . . . Hawaii was such a different animal. It would be like going from the earth to the moon. The whole atmosphere was different; the lighting was different, and the energy . . . Like literally a little shore break two-footer can just kick your ass! It can hit you in the knees and just knock you on your ass. Whereas in California, you just stand there and it goes by you and you kind of go, "Woo-hoo."

How did I deal with it? Sometimes I was so careful about looking at the swell direction, and waiting and watching the biggest set or sets, because Hawaii can trick you (or anywhere) you can go look and go, "Cool! It's like that, it's going to be easy." And you go home and get ready and meanwhile, you've missed the two-bomb sets because it's coming up, or something. So, you have to kind of watch it for twenty minutes or a half an hour, or a let a cycle of those long interval sets go through to see what's really happening.

But after a while, I got so good at it . . . It was different at different places. At Pipeline, I only went out when it was pure west, which meant it went from eight-foot to three-foot, which is a big barreling Pipe and it would go by like a big wedge and (Jeff now makes a sound effect like a turbine moving very fast and then slowing down) I would be in the channel kind of, and by the time it hit where I was in the channel (even though I was photographing the take-off which was 8 foot Hawaiian style) offshore with Rory (Russell) or Gerry (Lopez) or Jackie Dunn, it would go by so fast, like a triangle with a narrow tip and a large tip. At Sunset Beach I got so comfortable I wouldn't go out if I saw it was closing-out initially. On my initial look I probably wouldn't go out, but I would often go out when it was big and getting bigger, and I just handled it. It wasn't . . .

But after a while, I got so good at it . . . It was different at different places. At Pipeline, I only went out when it was pure west, which meant it went from eight-foot to three-foot, which is a big barreling Pipe and it would go by like a big wedge and (Jeff now makes a sound effect like a turbine moving very fast and then slowing down) I would be in the channel kind of, and by the time it hit where I was in the channel (even though I was photographing the take-off which was 8 foot Hawaiian style) offshore with Rory (Russell) or Gerry (Lopez) or Jackie Dunn, it would go by so fast, like a triangle with a narrow tip and a large tip. At Sunset Beach I got so comfortable I wouldn't go out if I saw it was closing-out initially. On my initial look I probably wouldn't go out, but I would often go out when it was big and getting bigger, and I just handled it. It wasn't . . .

Q: I mean, you didn't you prepare yourself in any psychological way? Create a state of mind to deal with it?

A: I never got scared. I learned not to talk to people and kind of be quiet, and keep watching the ocean, as I was getting ready. As soon as I started to talk to somebody, "Hey what," I would forget to do something with the equipment; not tighten a bolt down correctly or not put it on the right setting. I was so used to the ocean, like, paddling out at Black's on big bomb days, and getting stomped at Black's, you know, 150 times.

Q: Black's gets big, too.

A: The other thing is, in the back of my mind, I always knew, because of growing up and surfing pretty heavy waves in La Jolla, at Windansea & at Black's... there's one thing you always have to remember: YOU'RE NOT GOING TO DIE!

Q: I mean, you didn't you prepare yourself in any psychological way? Create a state of mind to deal with it?

A: I never got scared. I learned not to talk to people and kind of be quiet, and keep watching the ocean, as I was getting ready. As soon as I started to talk to somebody, "Hey what," I would forget to do something with the equipment; not tighten a bolt down correctly or not put it on the right setting. I was so used to the ocean, like, paddling out at Black's on big bomb days, and getting stomped at Black's, you know, 150 times.

Q: Black's gets big, too.

A: The other thing is, in the back of my mind, I always knew, because of growing up and surfing pretty heavy waves in La Jolla, at Windansea & at Black's... there's one thing you always have to remember: YOU'RE NOT GOING TO DIE!

You can get stomped, even in the Islands, where you just go "OH FU*K!" and bail and press all the alarm buttons. You're not going to die. You're going to get swept up, turned upside down like in a washing machine and you're going to pop up, pretty much... I always knew that well.

Q: You felt that way, even in really big surf? A: Big surf I'd freak out more, but even then, after you've been nailed, say, three or four or five times, you realize you're going to make it. I mean you can go through some pretty heavy scenarios, where you go a long way in the white water and it's hard to get a breath.

One time at Pipeline, I used to shoot Backdoor and in two different successions, I got bounced off the bottom. That really freaked me out. On one session, I was out there with Jack McCoy, and I got bounced off my butt really hard. There's this area where it's much shallower, where it's like a big shelf area, at Backdoor. I went "S--t! If that had been my head, I would have gotten F---ked . . .!"

Q: Is there anyway to define what makes a great surfing photograph? What elements need to be included in the photograph, in your opinion (in a broad sense) to make it great?

You can get stomped, even in the Islands, where you just go "OH FU*K!" and bail and press all the alarm buttons. You're not going to die. You're going to get swept up, turned upside down like in a washing machine and you're going to pop up, pretty much... I always knew that well.

Q: You felt that way, even in really big surf? A: Big surf I'd freak out more, but even then, after you've been nailed, say, three or four or five times, you realize you're going to make it. I mean you can go through some pretty heavy scenarios, where you go a long way in the white water and it's hard to get a breath.

One time at Pipeline, I used to shoot Backdoor and in two different successions, I got bounced off the bottom. That really freaked me out. On one session, I was out there with Jack McCoy, and I got bounced off my butt really hard. There's this area where it's much shallower, where it's like a big shelf area, at Backdoor. I went "S--t! If that had been my head, I would have gotten F---ked . . .!"

Q: Is there anyway to define what makes a great surfing photograph? What elements need to be included in the photograph, in your opinion (in a broad sense) to make it great?

A: (pause) Well... I have thought about that. There's a layer that's hard for me to punch out of . . . I . . . there are these parameters we've gone through in the history of surf photography . . . For example, the 'Stoner--Severson Era" was more moody, not necessarily perfectly shot; and then you had the era of the commercial Surf Magazine, in the 1980's where everything was perfectly shot, front lit, morning light, tack sharp, which is called " Larry Light" and a lot of that had to do with the printing of the magazines, which were so ill-printed, front lit, perfect lighting, bright and colorful (they printed better than the moody shots).

Q: Why did they call it "Larry Light"?

A: (pause) Well... I have thought about that. There's a layer that's hard for me to punch out of . . . I . . . there are these parameters we've gone through in the history of surf photography . . . For example, the 'Stoner--Severson Era" was more moody, not necessarily perfectly shot; and then you had the era of the commercial Surf Magazine, in the 1980's where everything was perfectly shot, front lit, morning light, tack sharp, which is called " Larry Light" and a lot of that had to do with the printing of the magazines, which were so ill-printed, front lit, perfect lighting, bright and colorful (they printed better than the moody shots).

Q: Why did they call it "Larry Light"?

A: Larry Light meant that you get up at dawn, when the sun is rising and go on a pier or a jetty or something, and you're looking at the surfer and he's front lit so all the colors come out. You can focus and he's sharp, so Larry Light is like morning light after a winter storm, where it's perfectly front-lit. Could be off a pier or a jetty, whatever, or off the beach...

So then, it went into an era where it went back again to kind of moody, when Rob Gilley became photo editor, they started using more moody-surfer-in-the-environment-type photos. It didn't matter if it was perfectly shot, if it had a mood to it.

If you come back to the foundation, your audience is a core group of surfers. The bottom line for a great surf photo is; the surfer on a wave.

A: Larry Light meant that you get up at dawn, when the sun is rising and go on a pier or a jetty or something, and you're looking at the surfer and he's front lit so all the colors come out. You can focus and he's sharp, so Larry Light is like morning light after a winter storm, where it's perfectly front-lit. Could be off a pier or a jetty, whatever, or off the beach...

So then, it went into an era where it went back again to kind of moody, when Rob Gilley became photo editor, they started using more moody-surfer-in-the-environment-type photos. It didn't matter if it was perfectly shot, if it had a mood to it.

If you come back to the foundation, your audience is a core group of surfers. The bottom line for a great surf photo is; the surfer on a wave.

It's the perfect fantasy wave, and/or the surfer in his environment: sand dunes, palm trees, the majesty of nature: Fantasy wave, perfect conditions.You can get deeper than that, too. You can get into the body language of the surfer, to a core surfer like you and I, we could look at 150 surf photos, taken by five different guys, and you and I, based on that core surfer-outlook, would come up with five photos that we think are the "A's".

Then you could take somebody else who's looking at it from this, say, perfect commercial sense: they would pick five different ones!

So there are different audiences. Our audience is this core group that can tell the difference in everything. They can tell, by the body language, who the surfer is.

It's the perfect fantasy wave, and/or the surfer in his environment: sand dunes, palm trees, the majesty of nature: Fantasy wave, perfect conditions.You can get deeper than that, too. You can get into the body language of the surfer, to a core surfer like you and I, we could look at 150 surf photos, taken by five different guys, and you and I, based on that core surfer-outlook, would come up with five photos that we think are the "A's".

Then you could take somebody else who's looking at it from this, say, perfect commercial sense: they would pick five different ones!

So there are different audiences. Our audience is this core group that can tell the difference in everything. They can tell, by the body language, who the surfer is.

Q: Were you consciously aware when you were shooting Rory (Russell), or especially Gerry (Lopez), or some of the other major surfers in Hawaii, were you consciously aware that you were making an effort to get photographs that truly defined their greatness or their individual style? Was it something you thought about?

A: In that time there were so few guys on the beach, it was beautiful.

Q: So you're talking about the 1970's?

A: Yes the 70's, a little of the 80's also, but the 70's were more romantic. There were only a handful of us photographers. I'd go check it out and go, "All right! West swell...I'm down there!" And depending on my mood, I'd have, let's say, the land lens, and I set up at an angle, because I knew Gerry and Rory and Jackie Dunn and those guys. They had rented a house there and it was a perfect front-lit sunny morning and here's come Jerry, he comes walking down the beach, and YEAH! I'm the only photographer around, and I'm photographing the greatest surfer in the world, and the show is about to begin, it was so exciting. This was before the Aussies came and all that.

In those days, there was a time when there were a handful of us; like, it could be an hour before another photographer showed up. It could be five minutes, but that little window of time, where you knew you were getting "it." You'd get so stoked because you knew you had captured something unique, that no one else had.

In that day you could build those times up, like, "Oh My God! I shot Rocky Point and all those guys were out, and no one else was there!" What you see now-a-days is that everybody's there. Every spot is filled, there's guys in the trees . . . up in the Da Da da Da Daaa! It's like a maggot scene, as Aaron Chang once said.