L

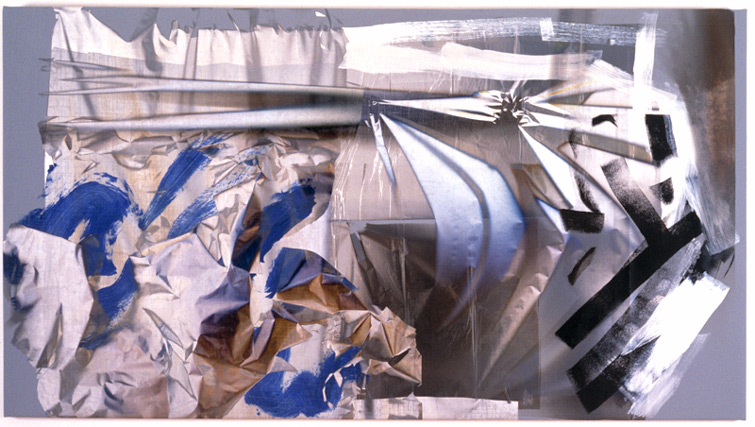

Larry Bell came to prominence in the burgeoning Los Angeles art scene during the 1960's as one of the originators of what came to be known as the "Light and Space" movement. Bell's work quickly gained momentum in New York and Los Angeles, expressing a newfound transcendence from traditional art that embodied an emerging and unique Los Angeles culture.

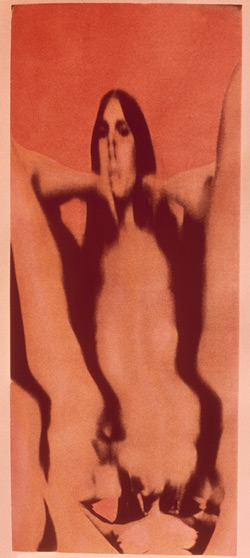

Bell's work zeros in on the properties of light upon surface; how it reflects light, absorbs light and how it interacts with light. Bell challenged the conventional mediums of art and sculpture, which limited his exploration of the properties of light and space. His collages and paintings celebrate light, form and color. Bell's infamous cubes extract the essence of light in expertly laminated surfaces that instruct and shape the visual experience.

Larry Bell's work can be found in museums and collections around the world. He was a featured artist in the Getty Foundation's Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture 1950-1970, exploring the historic emergence of art and culture in Los Angeles. Bell resides in Venice, California and also has a studio and residence in Taos New Mexico where he continues to be a lightening rod in the art scene.

AF: So, how and when did you recognize that you were an artist - or that you wanted to be an artist?

Larry Bell: I was in art school. I had gone off to Chouinard (Art Institute) after I graduated high school in '58 or '57, I don't remember.

My parents just said I could go to work, go to school, go to the army - but I couldn't sit and watch TV anymore. I had no aptitude or interest in anything, except I did draw cartoons when I was in high school. It occurred to me that I could find a professional school that had cartooning - and Chouinard was the training ground for Disney people. So I figured, well, I could go and learn how to be an animator and go to work for Disney.

AF: How old were you when you first started to draw?

LB: Oh, probably 15 or 16 or something like that, doodled cartoons and I liked MAD comic books . . .

AF: Alfred E. Newman . . .

LB: Yeah, right, and I liked that kind of humor and I used to draw little cartoon things.

Actually, I did it for my homework assignments. I would draw little cartoons dealing with whatever the questions were, with the little boxes and sound bubbles and so on.

AF: Was there any kind of an awakening, or any kind of an epiphany, or any kind of a moment?

Larry Bell: Yeah, there was. I found that part of the curriculum included painting and ceramics and fine arts things. That was a beginning thing - classes at art school, figure drawing and you know, perspective and design and whatever else. And general semantics, which was also a class, and I really liked the painting instructors. I liked their style better than the more technical people.

Besides, the cartooning and animation was something you did a couple of years after you'd been at art school, so I didn't have a shot at seeing what that was all about until I had taken a bunch of preliminary classes. So I just decided I would change my focus from wanting to be an animator to wanting to be a painter.

Mostly it was because of the personalities of the instructors. I found myself just being totally, totally infatuated with their style, their humor and everything about them was more real than anything else. So I decided this is what I wanted to do.

AF: You know a lot of people have used this word, "process." I was curious about how you would describe your "process"; are you methodical in your approach or more spontaneous? And how would you express your "process?"

LB: It depends on what aspect of my process. If it's a process of thinking, I try to be as spontaneous as possible. If it's a process of actual hands-on manipulation, I also try to be improvisational and be spontaneous. In certain of the plating aspects of my studio activities . . . I realize improvisation only works in a certain area. It doesn't work in mechanical ways because of the intricacies of the procedures that I use and surface treatment. It's an industrial process and there are certain basic rules that you have to consider. I might be able to improvise something in a Ruth Goldberg style to improvise getting through a certain kind of thing, but many times I can't do it. I have to plan the mechanics a lot less spontaneously than I would like.

AF: When you create your paintings and your sculpture, are the processes similar for you? Or are they very different for you?

LB: Well, they're different because the materials are different. The handling of the materials is completely different.

AF: Are there any similarities?

LB: The surface treatments are the same, yeah.

AF: The surface treatments? Can you elaborate on that a little bit?

Larry Bell: When I make glass sculptures I use thin films of various materials to coat the surfaces. That changes the nature of the light coming off the surface. But the coats are so thin they don't change what the surface looks like - just what the surface does.

Glass has three characteristics that I count on, and that's probably the biggest thing that makes me interested in it in the first place. It reflects, it transmits and it absorbs light all at the same time. So its possible to play around with three solid things; changing the absorption, or changing the reflection or changing the transmission characteristics of the material - thereby shaping the light that passes through.

Most of the sculptures are cube-like, and I was interested in shaping the light going through.

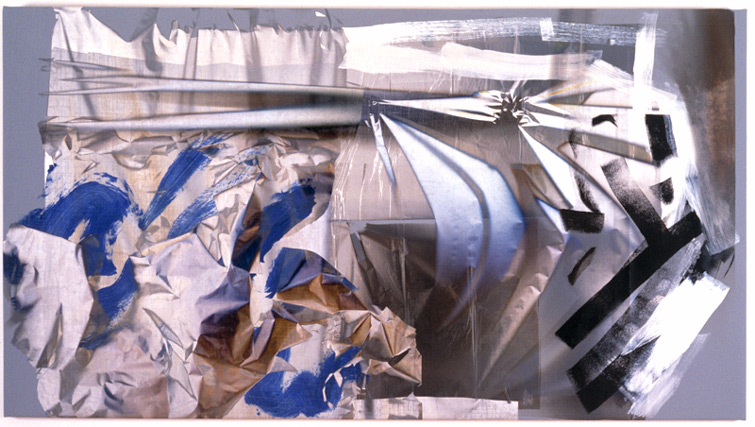

Then with the works on paper, paper doesn't transmit light. Paper reflects light and absorbs light. So the way I proceed with my improvisations with the paper is to try and keep the characteristics of having the feeling of paper but weaving the reflected and the absorbed lights together to make a tapestry that becomes an image. The image is made up from the light differentials on the surface.

In the case of most of the works that are around here, they're collages of layers of papers and Mylar and laminate that have been colored in my studio in New Mexico. I bring the parts here and I improvise with them.

Then with the works on paper, paper doesn't transmit light. Paper reflects light and absorbs light. So the way I proceed with my improvisations with the paper is to try and keep the characteristics of having the feeling of paper but weaving the reflected and the absorbed lights together to make a tapestry that becomes an image. The image is made up from the light differentials on the surface.

In the case of most of the works that are around here, they're collages of layers of papers and Mylar and laminate that have been colored in my studio in New Mexico. I bring the parts here and I improvise with them.

AF: Very interesting.

LB: And with the glasswork, which is also done in New Mexico, there is very little improvisation in the mechanics of the stuff. There are rules that I have to follow or else all of the time and effort that went into preparation of the surface will be wasted, or the surface itself will be wasted.

LB: And with the glasswork, which is also done in New Mexico, there is very little improvisation in the mechanics of the stuff. There are rules that I have to follow or else all of the time and effort that went into preparation of the surface will be wasted, or the surface itself will be wasted.

AF: Right. I was wondering what it is about translucency that appeals to you? I mean, what do you like about reflected color and light?

LB: Well, I like it in both. The sculptures are not so bright and the paper works have a lot of bright colors in them. I like the fact that the colors are natural; they're interference colors. There's very little pigment unless I choose to work on a surface that's, lets say, a red or a yellow paper.

But all of the treatments that cause other colors to be on those surfaces are interference colors, the same thing as you see when you go to a filling station and you see a puddle of water with a little gas on it. Those rainbow colors are caused by the very thickness of the gasoline interfering with wavelengths that are equivalent to the thickness of the gasoline.

When you see blue on the water, the gas is thinner than when you see red on the water. It just does that. It's a natural kind of phenomena. And in that case you're given the gift of seeing that because of where you are standing. But it's free; free and clean. And that's what I like about working with light off surface.

Basically, my trip is working with the free material, which is the light that did it, that we have around us.

LB: Well, I like it in both. The sculptures are not so bright and the paper works have a lot of bright colors in them. I like the fact that the colors are natural; they're interference colors. There's very little pigment unless I choose to work on a surface that's, lets say, a red or a yellow paper.

But all of the treatments that cause other colors to be on those surfaces are interference colors, the same thing as you see when you go to a filling station and you see a puddle of water with a little gas on it. Those rainbow colors are caused by the very thickness of the gasoline interfering with wavelengths that are equivalent to the thickness of the gasoline.

When you see blue on the water, the gas is thinner than when you see red on the water. It just does that. It's a natural kind of phenomena. And in that case you're given the gift of seeing that because of where you are standing. But it's free; free and clean. And that's what I like about working with light off surface.

Basically, my trip is working with the free material, which is the light that did it, that we have around us.

AF: Right.

LB: I count on the kinetics of the participant to move around the pieces to see how the light changes.

AF: You know I love you work, plain and simple. I photographed your sculptures years ago. I really appreciate them; they're just beautiful.

But, do you have a final vision of your sculptural pieces when you're creating them? All the way to the point of how they might be mounted? Do you think about the type of light that you would prefer that that piece be illuminated by? Like, is there such a thing as an optimum light for your pieces?

LB: Yes. I like ambient light - ambient daylight. I do not like shadows and I do not like reflections off of the glass pieces. I like to just show them bathed in the ambient light that comes in and they do whatever they do because of the volume of light or the lack of volume.

AF: So are you mostly talking about sunlight?

LB: Yes.

AF: Are you comfortable when you have to put in track lighting or tungsten lights?

LB: I just don't like to point light at my pieces.

AF: You prefer a bounced light?

LB: I like to come off the walls and create the ambient light for the space. I rarely put any light . . .

AF: . . . directly on them?

LB: Yeah, yeah.

AF: Because we have an audience that's based in photography on the website, I was curious about what interests you about the medium of photography? Has it influenced you as an artist very much? If so, how?

Larry Bell: Well, I fell in love with a camera. I had already begun my search for surfaces when I decided to build a larger plating apparatus to do larger glass sculptures. This was before I got into two-dimensional works.

They took two years to build the apparatus. It took about a year to find the company that could build it and a year for it to be built . . . and then, roughly a year to learn how to turn it on and off and learn how to do things with it

So during that three-year period, I stumbled across a camera called a Widelux. It was a panoramic camera and the first one I got was in a camera store. I think it was in New York, around 1965. I saw it in the window of a camera store and it had like a drum on it . . . a little barrel which fascinated me.

AF: Widelux's are legendary . . .

LB: And I went in to ask what that did, and the guy pushed a button and the lens moved. And that was all I needed; I was totally infatuated with the thing. And so I bought one and started playing around with it a little bit.

I was still working with the other equipment and when I stopped working with the coating equipment that I had - in my wait for the new equipment. I began to play seriously with this 35mm film camera. I carried it everywhere. I ended up with seven of them.

AF: Really?

LB: Yeah. I was a customer of Bel Air Camera all those years ago. I originally met Samy there. His uncle owned the store and he was immensely helpful. Each one was modified a little bit. I was able to change the shutter speed. Some of them were old ones that I had bought used . . .

And instead of a fifteenth of a second exposure, it had a tenth of a second exposure . . .

AF: Right. Did you shoot them hand-held?

LB: Yes, always.

AF: Never put it on a tripod?

LB: Maybe I put it on a tripod a few times, but . . .

AF: Normally not? What kind of things did you photograph?

LB: Whatever was goin' on. I liked to draw with it. I found that moving the camera, when the lens moved you could compress the light on a frame and end up with "drawings" that did things that were uncharacteristic of photographers.

I liked making pictures of things that I'd never seen before. And, not formal pictures of a portrait or anything - except that maybe they were portraits of, of feelings. And a lot of the images were totally abstracted by the distortion of moving the camera at the same time that the lens was moving and exposing the film.

AF: Right.

LB: You pull the camera a certain way (during exposure) when the lens is going that way . . . you got one kind of . . .

AF: Right.

LB: The other way it compressed the light and so on, and, and I kind of learned how to handwrite with the camera by simply moving it.

AF: Did you exhibit these images at all?

LB: No, I never paid much attention to them at all.

AF: I assume you had the film processed?

LB: Yes. Yes.

AF: On contact sheets, you made selections and all that?

Larry Bell: Not that I ever printed anything.

AF: Really?

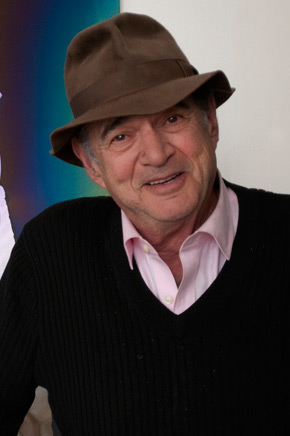

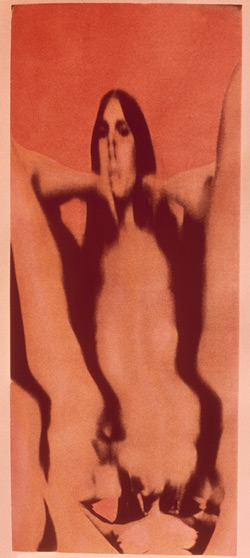

LB: I looked at the proof sheets and stuck them in the book. It was a time when I shot torsos; I would go to these funky model parlors in Hollywood. I'd bring seven Wideluxes; I'd rent the model for fifteen bucks for half an hour, then I would just go, just go crazy. I liked the fleshy tones and in this particular place that I liked to go to (its called the Hollywood Model Parlor) and, uh, its on Santa Monica Blvd. - not too far from Fairfax, they had this one great room that was "that color" pink, others where the walls were red; "that color" red.

AF: Wow.

LB: And so the flesh in that red and pink was spectacular, you know. The forms were glowing . . .

LB: And so the flesh in that red and pink was spectacular, you know. The forms were glowing . . .

AF: Right. So did you mostly use color film, color negative film?

LB: Yes and I used a of black and white.

AF: Really? That's great! I'd love to see those sometime.

LB: I have them all, the proofs and everything.

AF: Getting back to your sculptures for a moment, do you consider the cube to be an abstract form?

LB: No. I consider it to be an absolute symmetrical form.

AF: What is it about the cube that you find compelling? Is there something about it that you find compelling?

LB: It's totally symmetrical.

AF: Literally, like every surface is the same . . . like every dimension is pretty much identical to all the other dimensions?

LB: Yeah, yeah.

AF: I've noticed that your pieces are so magnificently finished. I mean they're extraordinary .

LB: Some of them.

AF: Well, at least many of the ones that I've seen, anyhow. But - Is that something that you started early on as an artist? The sense of everything being, in a certain sense, "perfect?"

LB: Yeah, yeah . . .

AF: Before you would show or exhibit it?

LB: Yeah. And that drove me crazy, the idea of "perfection." I mean I was after a certain kind of perfection. I was young. I had a lot of energy to put into doing that and there was a lot of time.

The search was always to reduce the number of elements that made up that sculpture - that made the visuals. Because the, the sculpture was one thing, but the feeling of the light was something else completely. So the form was what it was. I like the format of the cube because it had six sides and that made the variations possible within the format infinite and because you could rotate the parts so that the gradients on one panel would relate to gradients on the other panel. That was the only area that I had the ability to improvise in - the orientation of the sides in relation to each other . . .

Everything else there was no fucking around.

AF: Hmmm . . .

LB: And uh, so you could drop right in these things and condense light in them, and transmit light through them, and absorb light with them and you could endlessly make different pieces, even though the format was the same . . . And so, I just sort of tripped over the thing. I remember once, sometime ago, somebody asked me early on in my career whether the paintings of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian had impacted on me.

AF: Interesting question . . .

LB: It was an interesting question. I like Mondrian. There's no two ways about that.

AF: Me, too.

LB: But I realized then that probably the most influential things on my sculpture were the corners of the rooms that I worked out of and the right angles. Even now, just here, if I were to ask you to count the number of right angle relationships that impinge on your peripheral vision just sitting here in this room, you couldn't do it. There's too many.

It seemed to me the right angle, the corner, was the key element, the key influence to me; it was something that had to do with the way light came out of corners. And that's what I pursued.

AF: Color seems to figure predominately in your work, especially with the new collage pieces. How do you think about color? Do you think about it in terms of a design concept, or as more of an emotional issue?

LB: Emotional.

AF: I was curious about scale. I know you do some publicly commissioned pieces and I assume you would have to consider where the piece would be installed, where its going to go and how much space you'll have to work with. How do you adapt, as an artist, to those conditions?

LB: My public glass sculptures have not been very successful. They've been vandalized.

AF: Oh really? That's unfortunate.

LB: It's not a great material for that, at least the way I use it.

AF: I can see that; it's true. But in terms of your cubes, how do you decide how big they're going to be?

LB: Well, the real small ones are very difficult to make and the real big ones are also very difficult to make. Sometimes, I'll start with a certain size piece and make a series of it, and make all the glass panels, let's say, 15" square. Then that starts my operation. It's a comfortable size to work with. And I'll begin experimenting with them, coating parts, and I coat a lot of parts, and then set 'em down to look at them. With my technique I like to leave the parts sit for a couple of weeks to oxidize out. You get a hard film that will stay and they will eventually get harder than the glass itself . . .

AF: Oh really?

LB: Then they're less apt to be scratched and damaged when I pick 'em up to assemble them . . .

AF: Right, right . . .

LB: And after I've done a lot of parts, I'm sort of into my thing, and its time to assemble something and mix 'em in such a way that I know which edge goes to which edge, and after I'm tired of the 15", maybe I'll go up to the 20" ones or maybe I'll go down to 10". And if I get real ambitious I might try and make a 30" one or a 40" one.

AF: Do you see yourself as an alchemist?

LB: No, no.

AF: I mean in the sense that you turn one element into another?

LB: I don't think of myself as an alchemist. I don't think of myself as a minimalist. I don' think of myself as a pop artist. I don't think of myself as any of those things. I just think of myself as an artist having the right to stay unemployed and do my bit.

AF: (Laughter) That's interesting . . . I actually have a question about that. What do you think of the art world today, say, compared to when you had your first exhibit at the Ferus Gallery (In 1963)?

LB: Well, the art world today consists of a lot of people. And when I started, there were a handful of people. My art world was my few friends.

AF: Right. Right.

LB: That was it.

AF: . . . which were other local guys in Los Angeles, right?

LB: Right, right. Local guys, yeah.

AF: Like Ruscha, Baldessari, Moses and those guys, right? Did you influence each other very much, you think?

LB: I don't think so, other than humor. It is a great influence.

AF: Right

.

LB: And being silly was, was an important part of the trip. If you got too serious about it, it slowed you down. It took calories away from what should be spontaneity.

We talked earlier about this idea of "perfection." I realized that I was just smashing my head up against the wall because I was trying to make something that didn't have any scratches, didn't have any chips or things like that, and many of those things were not even visible! Only I could see them and so I decided to let myself off the hook and just try and make everything tolerable. If all the components were tolerable, then I might end up with something usable.

AF: Right, right . . .

LB: Otherwise, I was just going to be frustrated right into an early grave.

AF: Right, I understand what you mean . . .

LB: There just was no battling scratches; the material I chose to work with is susceptible to that and it had become very obvious. So, I just had to live with it.

AF What part of being an artist do you think you struggle with most?

LB: Oh, making a living.

AF: Really? So it's not an emotional issue or a time issue?

LB: It can become emotional but everybody has a right to make a living from their work. Everybody's right is there. But making art and making a living at art are two completely separate acts, and you've gotta keep 'em separate. But you can't have it become such an issue that it distracts you from your art.

AF: It's a matter of survival, somehow . . .

LB: Yeah. You've gotta somehow learn to walk a rope that's as thin as a spider's web. And at any time you can fall off and at any time it can break. And you know, that's just part of the given of the trip. The main thing is that you try and stay on it and enjoy the walk. Then, everything you see here is nothing more or less than a piece of evidence of a day's activity.

AF: I actually had a question like that, about what is a day in the life of Larry Bell like?

LB: I like to come in, in the morning, and have a few strong coffees, light up a cigar, look around and go to work with what I have. I surround myself with the materials that I prepare for myself. And go to work.

LB: I like to come in, in the morning, and have a few strong coffees, light up a cigar, look around and go to work with what I have. I surround myself with the materials that I prepare for myself. And go to work.

AF: Do you set up a disciplined schedule for yourself?

LB: I do if I have employees. If I have assistants it's nice to work with people you trust. And a lot of busy work is sort of boring stuff, so I like to have material prepared, glass cleaned, before I get into the actual coating technique. I like to have everything all ready to go and then I go after it and get it as fast as possible. After I've harvested what's useable, then, depending on the type of work I'm doing, I either make collage or sculptures.

If I'm doing the glass pieces, the glue takes a certain amount of time to dry. The cleaning of the surfaces before we coat it does, too. And then, after we've assembled it, it takes a certain amount of time to rest . . . all that kind of stuff. I like to flow on the creative edge, rather than on the detail of it.

If I'm doing the glass pieces, the glue takes a certain amount of time to dry. The cleaning of the surfaces before we coat it does, too. And then, after we've assembled it, it takes a certain amount of time to rest . . . all that kind of stuff. I like to flow on the creative edge, rather than on the detail of it.

AF: Do you seek the opinion of the people you've hired to work with you ever? I mean, do you ask them any aesthetic questions at all?

LB: No.

AF: Have you pretty much worked with the same assistants for many, many years?

LB: Yes.

AF: So they have a sense of your mindset already?

LB: Every once in a while, one will say something that is meaningful to me like, when I started doing these paper things and tearing stuff up and combining stuff up, a fellow who worked with me said, "This is really a great painted world." Just that little comment, you know, very encouraging and it meant a lot to me.

AF: Does politics influence your work and imagery at all?

LB: Just about everything outside of my studio is unacceptable and that includes politics.

AF: I'm sorry; did you say "unacceptable"?

LB: "Unacceptable," yeah.

AF: In terms of your process, in terms of what you create as an artist?

LB: In terms of, of everything that's meaningful to me, in the studio. Everything outside is politics . . . because in the studio, I am the tyrant. I am the boss. This is my scene. My ass is on the line here with what I do. I have no way to litigate the thought and debate. I don't live in the world of words. Plus, I'm very hard of hearing. I wear hearing aids. I hear things weird, too. I don't hear things that people say.

AF: Fragments?

LB: I hear things that I think they said.

AF: Oh, I see.

LB: Example: I ran into a friend of mine some years ago, hadn't seen in a long, long time. The normal questions, "How're you doing? Where are you living, blah blah blah. How's your wife?"

He said, "She left me."

I heard, "She joined the Navy."

You know, the conversation went on after that. "Where is she now," and it kept getting more and more oblique, until I asked him what her rank was? And he looked at me and he said, "What the fuck are you talking about?"

AF: (Laughter) Do you think the artist has any social responsibility? I mean to the culture that they live in or the civilization in general?

LB: Yes, I suppose so.

AF: But it's not something that you concern yourself with?

LB: Well, I think that I only concern myself with it by trying to be who I am here. In other words, if I have any influence or any importance whatsoever, it's the depth of my work, my investigations with surfaces. Nothing else.

AF: You said that the art world had changed in the sense that there are so many more people involved in it now. Did you mean that there are many more artists creating artwork than before? Or because of the significant increase in curatorial staffing at the museums? Also, the worldwide expansion of private galleries and dealers today is overwhelming. All these elements together, is that what you mean?

LB: It's an industry. I never even thought of it as a business. The art world is an industry. The studio is not an industry. It's not even a business for me, but something else. It has nothing to do with any of that stuff.

AF: Did you ever experience what writers refer to as "writer's block," or anything similar?

LB: Sure, sure.

AF: And you just pushed through it?

LB: I sit around, play the guitar, smoke dope, smoke cigars, drink beer and wait 'til my muse kicks my fucking Jewish ass out of my chair and it could go on for months. And at some point, I just get up out of the chair and go to work. And whatever the time of waiting, it almost always picks up exactly where it left off.

AF: Really?

LB: So I don't worry about these periods of low activity. They were almost always a by-product of being broke. I didn't have the money to buy materials. Or that nobody wanted to show the stuff; that nobody wanted to buy it; that nobody even wanted to come over and say hello. You know. That's cyclical. It happens.

AF: Its interesting because of course today, a lot of younger artists would not understand or recognize that maybe you had these kinds of really thin periods in your career.

LB: Why should they? It's none of their business. It is my reality.

AF: Right. And yet that's obviously a great challenge for any artist when they're financially challenged; how they cope and find a way to survive, to keep their faith in being an artist, to keep going.

LB: Look, the cube projects were very successful. I sold just about everything I ever made. But this had nothing to do with the "selling of things." That was always great. At the same time, however, I didn't make the things with the intent of selling them. I made them because that's all I knew how to do. And when I changed my interests from three-dimensional work to two-dimensional work, the interest in the things I was doing, which I was passionately in love with, fell off completely. There wasn't any interest in it. And, and so, that's the ebb and the flow. But what you have to do is trust yourself to do your thing. That's all that really counts.

AF: What are your feelings about the role of history and art history? Do you feel that as an artist, they were significant in your growth?

LB: I think there was a book I read once about the history of scientific revolution.

AF: The history of the scientific revolution?

LB: Yes, and I can't remember the writer's name. But he made a statement in the beginning, that the history of science actually really represents the history of the selection of scientific activity. And I have no reason to believe that the history of art is any different than that.

AF: Do you mean in terms of what art historians selected to be considered fine pieces of art and that other things weren't? But they could be equally worthy in your mind?

LB: Yeah . . . We all know great artists that are on their ass, that can't get any action, that are depressed because they can't participate for some reason or another, and they know in their hearts that their statements are as honest and as inventive as anything else that's going on out in the world - but they can't get the time of day. So uh, why? Who knows why? Something was selected to be a commodity and some things weren't.

AF: The process that you engage in with curators at museums - do you find that process challenging, or difficult? Have you learned anything by working with curators?

LB: I did a show recently in France and the curator's position on the show was to support an idea she had, which was that my work was as much related to the writing of science fiction as it was to minimalism. In other words, my work was influenced by science fiction as much as it was minimalism, maybe more. And she made a good case for it. I mean, I never thought of it before.

AF: Are you someone who avidly reads science fiction novels?

LB: I used to. I started off with H.G. Wells and I found him a fascinating writer. That led to reading other people. But Wells was the key guy for me. An anthology of his correspondence that I read, he had been a journalist in his younger days . . . A young journalist interviewing him after he had written the Time Machine and the Invisible Man,War of the Worlds, heavy duty stuff . . .

AF: Yes.

LB: . . . how he made the transition from being a journalist to being a successful novelist. And what he said to the guy was so meaningful to me. He said that he thought it wiser, to write a series of striking, if unfinished books, and so escape from journalism, rather than be forgotten while he elaborated on a masterpiece.

That meant to me that he was just going to work a lot. The good work would come and the bad work would come. But the main thing was that a lot of stuff was going to come and he was going to get his energy from the mass of stuff he was going through. And that's exactly how I felt about my stuff. Exactly.

That nothing that I did was going to be so great that it would make me immortal. And nothing that I did was going to be so bad that it was going to take me out of the scene. The main thing was to work.

Wells published about 138 novels while he was alive. I think 12 or 13 were published after he died. That's science books, history books . . . and he wrote a series of articles that were published around 1920. It was called or referred to as "the Outline of History," and it was published monthly. And that compendium of articles, I can't remember how many volumes there were to it, but they were done in a Life magazine style.

Science books and history books and, uh, his, uh, a series of articles that were published, I don't know, around 1920, in the '20's, I think, it was called, the Outline of History, published monthly, and that compendium of these things, I can't remember how many volumes there were to it, but they were sort of like a Life Magazine, and it became the normal history book used in high schools until it was outdated.

AF: Do you feel limited with the technology you apply, to create and finalize your works of art? In terms of what you perceive in your imagination, or what you desire to literally accomplish, that you are prevented from designing or inventing a new work of art - because the way to create it doesn't exist, technologically?

LB: No. But physically there's been a problem obtaining laminate film. I used to buy a dozen rolls of it every couple of years and when we got down to one roll of it, I asked my assistant in Taos to order some more. None of our distributors carried it anymore. And we couldn't find it and it was like, it had just disappeared in the year or so since we had ordered it last, it had just disappeared in the year or so since we had ordered it the last time. We finally located a company in Germany someplace that carried it. Except that the difference was I paid 180 bucks a roll for the stuff, plus UPS to get it to me.

AF: Right . . .

LB: Now I'm paying 500 Euros a roll, plus the shipping to get it from Germany. You know, that's a significant difference in cost.

AF: I understand . . . I mean, it's happened to me in my own work as a photographer. The papers have gotten ridiculously expensive.

LB: Yeah, yeah.

AF: Paper, just a single box of paper 16 x 20 inch black & white paper is close to two hundred dollars now.

LB: Do you shoot with film or digital?

AF: As an artist, I mostly work in film. But I mean, when I work for the website its better for me to shoot digitally because the web designer works with digital files. But I still love grain. Grain, to me, is like a metaphor for life . . .

LB: Well, for me, layering is a metaphor for life.

AF: Has the digital world influenced your artwork at all? I mean, do you use computers in any way?

Larry Bell: Only email.

AF: Email? Do you use the computer as a component in your creative process at all?

LB: Yes. I have.

AF: So, you do use it?

LB: Yes, I have.

AF: Did you embrace it?

Larry Bell: Oh I loved it! I tripped over it completely. Frank Gehry asked me to take a look at some models of a house that he was doing and I wanted to do some kind of collaboration at the time. So I took some images and scanned them into my little 165C Mac. I had a program that allowed me to draw on top of the scanned-in images.

AF: Right.

LB: And so, to illustrate the concept that I had, the program was very complicated. To me it was . . .

AF: You mean the software? Learning how to use it?

LB: Yeah, learning how to use the tools. I mean, I didn't know how to use it.

AF: Yeah, you mean, one of those (sketch) pads, or whatever?

Larry Bell: No, I was just working with the cursor bar and the side of my thumb. And looking at the screen, to see what a certain width of brush stroke would look like, I would turn my cursor ball fast or slow and watch on the screen what the evidence of my synergy was.

And then, because the thing didn't have much memory, I printed it out and wrote the settings on the paper; on letter bond paper.

I did the presentation of the light piece that I suggested might work for Frank's project, and showed it to him. He says, "Okay. This looks okay. Lets send it to the client and see what he says."

Larry Bell: No, I was just working with the cursor bar and the side of my thumb. And looking at the screen, to see what a certain width of brush stroke would look like, I would turn my cursor ball fast or slow and watch on the screen what the evidence of my synergy was.

And then, because the thing didn't have much memory, I printed it out and wrote the settings on the paper; on letter bond paper.

I did the presentation of the light piece that I suggested might work for Frank's project, and showed it to him. He says, "Okay. This looks okay. Lets send it to the client and see what he says."

So I ended up making a proposal for two giant bronzes that were taken from this, from this calligraphy and, uh, there's one here. I'll show it to you.

So I ended up making a proposal for two giant bronzes that were taken from this, from this calligraphy and, uh, there's one here. I'll show it to you.

AF: Could you explain a little bit about your Fraction Series and how that came to be? Or maybe you could express to the audience a little bit about the elements and the details that go into the art works?

Larry Bell: Well, I was working at doing collages on canvas and . . .

AF: Briefly, I'm sorry to interrupt you, but I had written a question about that, what is it about collage that interests you?

LB:It's just sort of like what you said about grain and texture.

AF: Oh, that the grain of film is like a metaphor for life?

LB:Yeah. Layers, layers of stuff that are a metaphor for life for me . . .

The layers, the thin layers that make the color, the layers of the papers that create the thing and just like we have layers of skin and the skin has layers within itself, and then there's the layers of who we are that - that we present to the public when we're dressing a certain way . . .

AF: Right, right.

LB:And then the layers of who we are inside our head that form how we think and go about things.

AF: What are the materials that you use on these?

LB:Paper, Mylar, laminate film and thin metal films and non-metallic films, like quartz.

AF: What is Mylar, exactly?

LB: It's a clear polycarbonate film that's very strong, doesn't burn easily and is crystal clear.

AF: I have one kind of dumb question. Um, is there any (laughter) . . . What was the worst question you were ever asked in an interview and have I asked it yet?

LB: No! Your questions have been great!

AF: Thank you. What interests you about physics, mathematics and science, in general? Anything at all?

Larry Bell :No, very little. I am neither a physicist nor a mathematician nor an engineer. I just do my thing with these tools that I've learned to use - because they satisfy my need for surface and light. I like the way light interfaces with surface. That's what these studies are all about. They're all about the light differentials that come off of different things because of the surface quality that the things themselves have.

So if you look at any one of these things closely you'll find that the textural differences are what make the depth. It has less to do with the color than it does with the dispersion characteristics that the varying surfaces have . . .

AF: So this journey that you chose to take in your life, to be an artist, have you found any real surprises that you didn't anticipate?

LB: Yes. How much . . . how selfish it is.

LB: Yes. How much . . . how selfish it is.

AF: In what sense?

LB: Well -- to be honest to your thing, at least for me, I found that it impacted on my family and the time I spent with my children and - it wasn't' like a job. It wasn't eight hours at work and the rest is family and so on, it was 100% of the time. And the distraction of the work from family issues was really hard on my family and, particularly hard on the wonderful woman who was my mate for 30 years. And then, you know, she finally just decided, "I don't want to live like this anymore." And we split up.

That's when I came back to Venice. It's, it's hard to be an artist. It's not an easy thing. But in some cases, it's much easier than getting a job.

AF: You know, I think we covered a lot today and I'd like to sincerely thank you for your time doing this interview for Samy's website. And now maybe we could do some photos of you working in your studio . . .?

LB: Yeah. Sure.

Larry Bell came to prominence in the burgeoning Los Angeles art scene during the 1960's as one of the originators of what came to be known as the "Light and Space" movement. Bell's work quickly gained momentum in New York and Los Angeles, expressing a newfound transcendence from traditional art that embodied an emerging and unique Los Angeles culture.

Bell's work zeros in on the properties of light upon surface; how it reflects light, absorbs light and how it interacts with light. Bell challenged the conventional mediums of art and sculpture, which limited his exploration of the properties of light and space. His collages and paintings celebrate light, form and color. Bell's infamous cubes extract the essence of light in expertly laminated surfaces that instruct and shape the visual experience.

Larry Bell's work can be found in museums and collections around the world. He was a featured artist in the Getty Foundation's Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture 1950-1970, exploring the historic emergence of art and culture in Los Angeles. Bell resides in Venice, California and also has a studio and residence in Taos New Mexico where he continues to be a lightening rod in the art scene.

Larry Bell came to prominence in the burgeoning Los Angeles art scene during the 1960's as one of the originators of what came to be known as the "Light and Space" movement. Bell's work quickly gained momentum in New York and Los Angeles, expressing a newfound transcendence from traditional art that embodied an emerging and unique Los Angeles culture.

Bell's work zeros in on the properties of light upon surface; how it reflects light, absorbs light and how it interacts with light. Bell challenged the conventional mediums of art and sculpture, which limited his exploration of the properties of light and space. His collages and paintings celebrate light, form and color. Bell's infamous cubes extract the essence of light in expertly laminated surfaces that instruct and shape the visual experience.

Larry Bell's work can be found in museums and collections around the world. He was a featured artist in the Getty Foundation's Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture 1950-1970, exploring the historic emergence of art and culture in Los Angeles. Bell resides in Venice, California and also has a studio and residence in Taos New Mexico where he continues to be a lightening rod in the art scene.

AF: So, how and when did you recognize that you were an artist - or that you wanted to be an artist?

Larry Bell: I was in art school. I had gone off to Chouinard (Art Institute) after I graduated high school in '58 or '57, I don't remember.

My parents just said I could go to work, go to school, go to the army - but I couldn't sit and watch TV anymore. I had no aptitude or interest in anything, except I did draw cartoons when I was in high school. It occurred to me that I could find a professional school that had cartooning - and Chouinard was the training ground for Disney people. So I figured, well, I could go and learn how to be an animator and go to work for Disney.

AF: How old were you when you first started to draw?

LB: Oh, probably 15 or 16 or something like that, doodled cartoons and I liked MAD comic books . . .

AF: Alfred E. Newman . . .

LB: Yeah, right, and I liked that kind of humor and I used to draw little cartoon things.

Actually, I did it for my homework assignments. I would draw little cartoons dealing with whatever the questions were, with the little boxes and sound bubbles and so on.

AF: Was there any kind of an awakening, or any kind of an epiphany, or any kind of a moment?

Larry Bell: Yeah, there was. I found that part of the curriculum included painting and ceramics and fine arts things. That was a beginning thing - classes at art school, figure drawing and you know, perspective and design and whatever else. And general semantics, which was also a class, and I really liked the painting instructors. I liked their style better than the more technical people.

Besides, the cartooning and animation was something you did a couple of years after you'd been at art school, so I didn't have a shot at seeing what that was all about until I had taken a bunch of preliminary classes. So I just decided I would change my focus from wanting to be an animator to wanting to be a painter.

Mostly it was because of the personalities of the instructors. I found myself just being totally, totally infatuated with their style, their humor and everything about them was more real than anything else. So I decided this is what I wanted to do.

AF: You know a lot of people have used this word, "process." I was curious about how you would describe your "process"; are you methodical in your approach or more spontaneous? And how would you express your "process?"

LB: It depends on what aspect of my process. If it's a process of thinking, I try to be as spontaneous as possible. If it's a process of actual hands-on manipulation, I also try to be improvisational and be spontaneous. In certain of the plating aspects of my studio activities . . . I realize improvisation only works in a certain area. It doesn't work in mechanical ways because of the intricacies of the procedures that I use and surface treatment. It's an industrial process and there are certain basic rules that you have to consider. I might be able to improvise something in a Ruth Goldberg style to improvise getting through a certain kind of thing, but many times I can't do it. I have to plan the mechanics a lot less spontaneously than I would like.

AF: When you create your paintings and your sculpture, are the processes similar for you? Or are they very different for you?

LB: Well, they're different because the materials are different. The handling of the materials is completely different.

AF: Are there any similarities?

LB: The surface treatments are the same, yeah.

AF: The surface treatments? Can you elaborate on that a little bit?

Larry Bell: When I make glass sculptures I use thin films of various materials to coat the surfaces. That changes the nature of the light coming off the surface. But the coats are so thin they don't change what the surface looks like - just what the surface does.

Glass has three characteristics that I count on, and that's probably the biggest thing that makes me interested in it in the first place. It reflects, it transmits and it absorbs light all at the same time. So its possible to play around with three solid things; changing the absorption, or changing the reflection or changing the transmission characteristics of the material - thereby shaping the light that passes through.

Most of the sculptures are cube-like, and I was interested in shaping the light going through.

AF: So, how and when did you recognize that you were an artist - or that you wanted to be an artist?

Larry Bell: I was in art school. I had gone off to Chouinard (Art Institute) after I graduated high school in '58 or '57, I don't remember.

My parents just said I could go to work, go to school, go to the army - but I couldn't sit and watch TV anymore. I had no aptitude or interest in anything, except I did draw cartoons when I was in high school. It occurred to me that I could find a professional school that had cartooning - and Chouinard was the training ground for Disney people. So I figured, well, I could go and learn how to be an animator and go to work for Disney.

AF: How old were you when you first started to draw?

LB: Oh, probably 15 or 16 or something like that, doodled cartoons and I liked MAD comic books . . .

AF: Alfred E. Newman . . .

LB: Yeah, right, and I liked that kind of humor and I used to draw little cartoon things.

Actually, I did it for my homework assignments. I would draw little cartoons dealing with whatever the questions were, with the little boxes and sound bubbles and so on.

AF: Was there any kind of an awakening, or any kind of an epiphany, or any kind of a moment?

Larry Bell: Yeah, there was. I found that part of the curriculum included painting and ceramics and fine arts things. That was a beginning thing - classes at art school, figure drawing and you know, perspective and design and whatever else. And general semantics, which was also a class, and I really liked the painting instructors. I liked their style better than the more technical people.

Besides, the cartooning and animation was something you did a couple of years after you'd been at art school, so I didn't have a shot at seeing what that was all about until I had taken a bunch of preliminary classes. So I just decided I would change my focus from wanting to be an animator to wanting to be a painter.

Mostly it was because of the personalities of the instructors. I found myself just being totally, totally infatuated with their style, their humor and everything about them was more real than anything else. So I decided this is what I wanted to do.

AF: You know a lot of people have used this word, "process." I was curious about how you would describe your "process"; are you methodical in your approach or more spontaneous? And how would you express your "process?"

LB: It depends on what aspect of my process. If it's a process of thinking, I try to be as spontaneous as possible. If it's a process of actual hands-on manipulation, I also try to be improvisational and be spontaneous. In certain of the plating aspects of my studio activities . . . I realize improvisation only works in a certain area. It doesn't work in mechanical ways because of the intricacies of the procedures that I use and surface treatment. It's an industrial process and there are certain basic rules that you have to consider. I might be able to improvise something in a Ruth Goldberg style to improvise getting through a certain kind of thing, but many times I can't do it. I have to plan the mechanics a lot less spontaneously than I would like.

AF: When you create your paintings and your sculpture, are the processes similar for you? Or are they very different for you?

LB: Well, they're different because the materials are different. The handling of the materials is completely different.

AF: Are there any similarities?

LB: The surface treatments are the same, yeah.

AF: The surface treatments? Can you elaborate on that a little bit?

Larry Bell: When I make glass sculptures I use thin films of various materials to coat the surfaces. That changes the nature of the light coming off the surface. But the coats are so thin they don't change what the surface looks like - just what the surface does.

Glass has three characteristics that I count on, and that's probably the biggest thing that makes me interested in it in the first place. It reflects, it transmits and it absorbs light all at the same time. So its possible to play around with three solid things; changing the absorption, or changing the reflection or changing the transmission characteristics of the material - thereby shaping the light that passes through.

Most of the sculptures are cube-like, and I was interested in shaping the light going through.

Then with the works on paper, paper doesn't transmit light. Paper reflects light and absorbs light. So the way I proceed with my improvisations with the paper is to try and keep the characteristics of having the feeling of paper but weaving the reflected and the absorbed lights together to make a tapestry that becomes an image. The image is made up from the light differentials on the surface.

In the case of most of the works that are around here, they're collages of layers of papers and Mylar and laminate that have been colored in my studio in New Mexico. I bring the parts here and I improvise with them.

AF: Very interesting.

Then with the works on paper, paper doesn't transmit light. Paper reflects light and absorbs light. So the way I proceed with my improvisations with the paper is to try and keep the characteristics of having the feeling of paper but weaving the reflected and the absorbed lights together to make a tapestry that becomes an image. The image is made up from the light differentials on the surface.

In the case of most of the works that are around here, they're collages of layers of papers and Mylar and laminate that have been colored in my studio in New Mexico. I bring the parts here and I improvise with them.

AF: Very interesting.

LB: And with the glasswork, which is also done in New Mexico, there is very little improvisation in the mechanics of the stuff. There are rules that I have to follow or else all of the time and effort that went into preparation of the surface will be wasted, or the surface itself will be wasted.

AF: Right. I was wondering what it is about translucency that appeals to you? I mean, what do you like about reflected color and light?

LB: And with the glasswork, which is also done in New Mexico, there is very little improvisation in the mechanics of the stuff. There are rules that I have to follow or else all of the time and effort that went into preparation of the surface will be wasted, or the surface itself will be wasted.

AF: Right. I was wondering what it is about translucency that appeals to you? I mean, what do you like about reflected color and light?

LB: Well, I like it in both. The sculptures are not so bright and the paper works have a lot of bright colors in them. I like the fact that the colors are natural; they're interference colors. There's very little pigment unless I choose to work on a surface that's, lets say, a red or a yellow paper.

But all of the treatments that cause other colors to be on those surfaces are interference colors, the same thing as you see when you go to a filling station and you see a puddle of water with a little gas on it. Those rainbow colors are caused by the very thickness of the gasoline interfering with wavelengths that are equivalent to the thickness of the gasoline.

When you see blue on the water, the gas is thinner than when you see red on the water. It just does that. It's a natural kind of phenomena. And in that case you're given the gift of seeing that because of where you are standing. But it's free; free and clean. And that's what I like about working with light off surface.

Basically, my trip is working with the free material, which is the light that did it, that we have around us.

AF: Right.

LB: I count on the kinetics of the participant to move around the pieces to see how the light changes.

AF: You know I love you work, plain and simple. I photographed your sculptures years ago. I really appreciate them; they're just beautiful.

But, do you have a final vision of your sculptural pieces when you're creating them? All the way to the point of how they might be mounted? Do you think about the type of light that you would prefer that that piece be illuminated by? Like, is there such a thing as an optimum light for your pieces?

LB: Yes. I like ambient light - ambient daylight. I do not like shadows and I do not like reflections off of the glass pieces. I like to just show them bathed in the ambient light that comes in and they do whatever they do because of the volume of light or the lack of volume.

AF: So are you mostly talking about sunlight?

LB: Yes.

AF: Are you comfortable when you have to put in track lighting or tungsten lights?

LB: I just don't like to point light at my pieces.

AF: You prefer a bounced light?

LB: I like to come off the walls and create the ambient light for the space. I rarely put any light . . .

AF: . . . directly on them?

LB: Yeah, yeah.

AF: Because we have an audience that's based in photography on the website, I was curious about what interests you about the medium of photography? Has it influenced you as an artist very much? If so, how?

Larry Bell: Well, I fell in love with a camera. I had already begun my search for surfaces when I decided to build a larger plating apparatus to do larger glass sculptures. This was before I got into two-dimensional works.

They took two years to build the apparatus. It took about a year to find the company that could build it and a year for it to be built . . . and then, roughly a year to learn how to turn it on and off and learn how to do things with it

So during that three-year period, I stumbled across a camera called a Widelux. It was a panoramic camera and the first one I got was in a camera store. I think it was in New York, around 1965. I saw it in the window of a camera store and it had like a drum on it . . . a little barrel which fascinated me.

AF: Widelux's are legendary . . .

LB: And I went in to ask what that did, and the guy pushed a button and the lens moved. And that was all I needed; I was totally infatuated with the thing. And so I bought one and started playing around with it a little bit.

I was still working with the other equipment and when I stopped working with the coating equipment that I had - in my wait for the new equipment. I began to play seriously with this 35mm film camera. I carried it everywhere. I ended up with seven of them.

AF: Really?

LB: Yeah. I was a customer of Bel Air Camera all those years ago. I originally met Samy there. His uncle owned the store and he was immensely helpful. Each one was modified a little bit. I was able to change the shutter speed. Some of them were old ones that I had bought used . . .

And instead of a fifteenth of a second exposure, it had a tenth of a second exposure . . .

AF: Right. Did you shoot them hand-held?

LB: Yes, always.

AF: Never put it on a tripod?

LB: Maybe I put it on a tripod a few times, but . . .

AF: Normally not? What kind of things did you photograph?

LB: Whatever was goin' on. I liked to draw with it. I found that moving the camera, when the lens moved you could compress the light on a frame and end up with "drawings" that did things that were uncharacteristic of photographers.

I liked making pictures of things that I'd never seen before. And, not formal pictures of a portrait or anything - except that maybe they were portraits of, of feelings. And a lot of the images were totally abstracted by the distortion of moving the camera at the same time that the lens was moving and exposing the film.

AF: Right.

LB: You pull the camera a certain way (during exposure) when the lens is going that way . . . you got one kind of . . .

AF: Right.

LB: The other way it compressed the light and so on, and, and I kind of learned how to handwrite with the camera by simply moving it.

AF: Did you exhibit these images at all?

LB: No, I never paid much attention to them at all.

AF: I assume you had the film processed?

LB: Yes. Yes.

AF: On contact sheets, you made selections and all that?

Larry Bell: Not that I ever printed anything.

AF: Really?

LB: I looked at the proof sheets and stuck them in the book. It was a time when I shot torsos; I would go to these funky model parlors in Hollywood. I'd bring seven Wideluxes; I'd rent the model for fifteen bucks for half an hour, then I would just go, just go crazy. I liked the fleshy tones and in this particular place that I liked to go to (its called the Hollywood Model Parlor) and, uh, its on Santa Monica Blvd. - not too far from Fairfax, they had this one great room that was "that color" pink, others where the walls were red; "that color" red.

AF: Wow.

LB: Well, I like it in both. The sculptures are not so bright and the paper works have a lot of bright colors in them. I like the fact that the colors are natural; they're interference colors. There's very little pigment unless I choose to work on a surface that's, lets say, a red or a yellow paper.

But all of the treatments that cause other colors to be on those surfaces are interference colors, the same thing as you see when you go to a filling station and you see a puddle of water with a little gas on it. Those rainbow colors are caused by the very thickness of the gasoline interfering with wavelengths that are equivalent to the thickness of the gasoline.

When you see blue on the water, the gas is thinner than when you see red on the water. It just does that. It's a natural kind of phenomena. And in that case you're given the gift of seeing that because of where you are standing. But it's free; free and clean. And that's what I like about working with light off surface.

Basically, my trip is working with the free material, which is the light that did it, that we have around us.

AF: Right.

LB: I count on the kinetics of the participant to move around the pieces to see how the light changes.

AF: You know I love you work, plain and simple. I photographed your sculptures years ago. I really appreciate them; they're just beautiful.

But, do you have a final vision of your sculptural pieces when you're creating them? All the way to the point of how they might be mounted? Do you think about the type of light that you would prefer that that piece be illuminated by? Like, is there such a thing as an optimum light for your pieces?

LB: Yes. I like ambient light - ambient daylight. I do not like shadows and I do not like reflections off of the glass pieces. I like to just show them bathed in the ambient light that comes in and they do whatever they do because of the volume of light or the lack of volume.

AF: So are you mostly talking about sunlight?

LB: Yes.

AF: Are you comfortable when you have to put in track lighting or tungsten lights?

LB: I just don't like to point light at my pieces.

AF: You prefer a bounced light?

LB: I like to come off the walls and create the ambient light for the space. I rarely put any light . . .

AF: . . . directly on them?

LB: Yeah, yeah.

AF: Because we have an audience that's based in photography on the website, I was curious about what interests you about the medium of photography? Has it influenced you as an artist very much? If so, how?

Larry Bell: Well, I fell in love with a camera. I had already begun my search for surfaces when I decided to build a larger plating apparatus to do larger glass sculptures. This was before I got into two-dimensional works.

They took two years to build the apparatus. It took about a year to find the company that could build it and a year for it to be built . . . and then, roughly a year to learn how to turn it on and off and learn how to do things with it

So during that three-year period, I stumbled across a camera called a Widelux. It was a panoramic camera and the first one I got was in a camera store. I think it was in New York, around 1965. I saw it in the window of a camera store and it had like a drum on it . . . a little barrel which fascinated me.

AF: Widelux's are legendary . . .

LB: And I went in to ask what that did, and the guy pushed a button and the lens moved. And that was all I needed; I was totally infatuated with the thing. And so I bought one and started playing around with it a little bit.

I was still working with the other equipment and when I stopped working with the coating equipment that I had - in my wait for the new equipment. I began to play seriously with this 35mm film camera. I carried it everywhere. I ended up with seven of them.

AF: Really?

LB: Yeah. I was a customer of Bel Air Camera all those years ago. I originally met Samy there. His uncle owned the store and he was immensely helpful. Each one was modified a little bit. I was able to change the shutter speed. Some of them were old ones that I had bought used . . .

And instead of a fifteenth of a second exposure, it had a tenth of a second exposure . . .

AF: Right. Did you shoot them hand-held?

LB: Yes, always.

AF: Never put it on a tripod?

LB: Maybe I put it on a tripod a few times, but . . .

AF: Normally not? What kind of things did you photograph?

LB: Whatever was goin' on. I liked to draw with it. I found that moving the camera, when the lens moved you could compress the light on a frame and end up with "drawings" that did things that were uncharacteristic of photographers.

I liked making pictures of things that I'd never seen before. And, not formal pictures of a portrait or anything - except that maybe they were portraits of, of feelings. And a lot of the images were totally abstracted by the distortion of moving the camera at the same time that the lens was moving and exposing the film.

AF: Right.

LB: You pull the camera a certain way (during exposure) when the lens is going that way . . . you got one kind of . . .

AF: Right.

LB: The other way it compressed the light and so on, and, and I kind of learned how to handwrite with the camera by simply moving it.

AF: Did you exhibit these images at all?

LB: No, I never paid much attention to them at all.

AF: I assume you had the film processed?

LB: Yes. Yes.

AF: On contact sheets, you made selections and all that?

Larry Bell: Not that I ever printed anything.

AF: Really?

LB: I looked at the proof sheets and stuck them in the book. It was a time when I shot torsos; I would go to these funky model parlors in Hollywood. I'd bring seven Wideluxes; I'd rent the model for fifteen bucks for half an hour, then I would just go, just go crazy. I liked the fleshy tones and in this particular place that I liked to go to (its called the Hollywood Model Parlor) and, uh, its on Santa Monica Blvd. - not too far from Fairfax, they had this one great room that was "that color" pink, others where the walls were red; "that color" red.

AF: Wow.

LB: And so the flesh in that red and pink was spectacular, you know. The forms were glowing . . .

AF: Right. So did you mostly use color film, color negative film?

LB: Yes and I used a of black and white.

AF: Really? That's great! I'd love to see those sometime.

LB: I have them all, the proofs and everything.

AF: Getting back to your sculptures for a moment, do you consider the cube to be an abstract form?

LB: No. I consider it to be an absolute symmetrical form.

AF: What is it about the cube that you find compelling? Is there something about it that you find compelling?

LB: It's totally symmetrical.

AF: Literally, like every surface is the same . . . like every dimension is pretty much identical to all the other dimensions?

LB: Yeah, yeah.

AF: I've noticed that your pieces are so magnificently finished. I mean they're extraordinary .

LB: Some of them.

AF: Well, at least many of the ones that I've seen, anyhow. But - Is that something that you started early on as an artist? The sense of everything being, in a certain sense, "perfect?"

LB: Yeah, yeah . . .

AF: Before you would show or exhibit it?

LB: Yeah. And that drove me crazy, the idea of "perfection." I mean I was after a certain kind of perfection. I was young. I had a lot of energy to put into doing that and there was a lot of time.

The search was always to reduce the number of elements that made up that sculpture - that made the visuals. Because the, the sculpture was one thing, but the feeling of the light was something else completely. So the form was what it was. I like the format of the cube because it had six sides and that made the variations possible within the format infinite and because you could rotate the parts so that the gradients on one panel would relate to gradients on the other panel. That was the only area that I had the ability to improvise in - the orientation of the sides in relation to each other . . .

Everything else there was no fucking around.

AF: Hmmm . . .

LB: And uh, so you could drop right in these things and condense light in them, and transmit light through them, and absorb light with them and you could endlessly make different pieces, even though the format was the same . . . And so, I just sort of tripped over the thing. I remember once, sometime ago, somebody asked me early on in my career whether the paintings of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian had impacted on me.

AF: Interesting question . . .

LB: It was an interesting question. I like Mondrian. There's no two ways about that.

AF: Me, too.

LB: But I realized then that probably the most influential things on my sculpture were the corners of the rooms that I worked out of and the right angles. Even now, just here, if I were to ask you to count the number of right angle relationships that impinge on your peripheral vision just sitting here in this room, you couldn't do it. There's too many.

It seemed to me the right angle, the corner, was the key element, the key influence to me; it was something that had to do with the way light came out of corners. And that's what I pursued.

LB: And so the flesh in that red and pink was spectacular, you know. The forms were glowing . . .

AF: Right. So did you mostly use color film, color negative film?

LB: Yes and I used a of black and white.

AF: Really? That's great! I'd love to see those sometime.

LB: I have them all, the proofs and everything.

AF: Getting back to your sculptures for a moment, do you consider the cube to be an abstract form?

LB: No. I consider it to be an absolute symmetrical form.

AF: What is it about the cube that you find compelling? Is there something about it that you find compelling?

LB: It's totally symmetrical.

AF: Literally, like every surface is the same . . . like every dimension is pretty much identical to all the other dimensions?

LB: Yeah, yeah.

AF: I've noticed that your pieces are so magnificently finished. I mean they're extraordinary .

LB: Some of them.

AF: Well, at least many of the ones that I've seen, anyhow. But - Is that something that you started early on as an artist? The sense of everything being, in a certain sense, "perfect?"

LB: Yeah, yeah . . .

AF: Before you would show or exhibit it?

LB: Yeah. And that drove me crazy, the idea of "perfection." I mean I was after a certain kind of perfection. I was young. I had a lot of energy to put into doing that and there was a lot of time.

The search was always to reduce the number of elements that made up that sculpture - that made the visuals. Because the, the sculpture was one thing, but the feeling of the light was something else completely. So the form was what it was. I like the format of the cube because it had six sides and that made the variations possible within the format infinite and because you could rotate the parts so that the gradients on one panel would relate to gradients on the other panel. That was the only area that I had the ability to improvise in - the orientation of the sides in relation to each other . . .

Everything else there was no fucking around.

AF: Hmmm . . .

LB: And uh, so you could drop right in these things and condense light in them, and transmit light through them, and absorb light with them and you could endlessly make different pieces, even though the format was the same . . . And so, I just sort of tripped over the thing. I remember once, sometime ago, somebody asked me early on in my career whether the paintings of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian had impacted on me.

AF: Interesting question . . .

LB: It was an interesting question. I like Mondrian. There's no two ways about that.

AF: Me, too.

LB: But I realized then that probably the most influential things on my sculpture were the corners of the rooms that I worked out of and the right angles. Even now, just here, if I were to ask you to count the number of right angle relationships that impinge on your peripheral vision just sitting here in this room, you couldn't do it. There's too many.

It seemed to me the right angle, the corner, was the key element, the key influence to me; it was something that had to do with the way light came out of corners. And that's what I pursued.

AF: Color seems to figure predominately in your work, especially with the new collage pieces. How do you think about color? Do you think about it in terms of a design concept, or as more of an emotional issue?

LB: Emotional.

AF: Color seems to figure predominately in your work, especially with the new collage pieces. How do you think about color? Do you think about it in terms of a design concept, or as more of an emotional issue?

LB: Emotional.

AF: I was curious about scale. I know you do some publicly commissioned pieces and I assume you would have to consider where the piece would be installed, where its going to go and how much space you'll have to work with. How do you adapt, as an artist, to those conditions?

LB: My public glass sculptures have not been very successful. They've been vandalized.

AF: Oh really? That's unfortunate.

LB: It's not a great material for that, at least the way I use it.

AF: I can see that; it's true. But in terms of your cubes, how do you decide how big they're going to be?

LB: Well, the real small ones are very difficult to make and the real big ones are also very difficult to make. Sometimes, I'll start with a certain size piece and make a series of it, and make all the glass panels, let's say, 15" square. Then that starts my operation. It's a comfortable size to work with. And I'll begin experimenting with them, coating parts, and I coat a lot of parts, and then set 'em down to look at them. With my technique I like to leave the parts sit for a couple of weeks to oxidize out. You get a hard film that will stay and they will eventually get harder than the glass itself . . .

AF: Oh really?

LB: Then they're less apt to be scratched and damaged when I pick 'em up to assemble them . . .

AF: Right, right . . .

LB: And after I've done a lot of parts, I'm sort of into my thing, and its time to assemble something and mix 'em in such a way that I know which edge goes to which edge, and after I'm tired of the 15", maybe I'll go up to the 20" ones or maybe I'll go down to 10". And if I get real ambitious I might try and make a 30" one or a 40" one.

AF: Do you see yourself as an alchemist?

LB: No, no.

AF: I mean in the sense that you turn one element into another?

LB: I don't think of myself as an alchemist. I don't think of myself as a minimalist. I don' think of myself as a pop artist. I don't think of myself as any of those things. I just think of myself as an artist having the right to stay unemployed and do my bit.

AF: (Laughter) That's interesting . . . I actually have a question about that. What do you think of the art world today, say, compared to when you had your first exhibit at the Ferus Gallery (In 1963)?

LB: Well, the art world today consists of a lot of people. And when I started, there were a handful of people. My art world was my few friends.

AF: Right. Right.

LB: That was it.

AF: . . . which were other local guys in Los Angeles, right?

LB: Right, right. Local guys, yeah.

AF: Like Ruscha, Baldessari, Moses and those guys, right? Did you influence each other very much, you think?

LB: I don't think so, other than humor. It is a great influence.

AF: Right.

LB: And being silly was, was an important part of the trip. If you got too serious about it, it slowed you down. It took calories away from what should be spontaneity.

We talked earlier about this idea of "perfection." I realized that I was just smashing my head up against the wall because I was trying to make something that didn't have any scratches, didn't have any chips or things like that, and many of those things were not even visible! Only I could see them and so I decided to let myself off the hook and just try and make everything tolerable. If all the components were tolerable, then I might end up with something usable.

AF: Right, right . . .

LB: Otherwise, I was just going to be frustrated right into an early grave.

AF: Right, I understand what you mean . . .

LB: There just was no battling scratches; the material I chose to work with is susceptible to that and it had become very obvious. So, I just had to live with it.

AF What part of being an artist do you think you struggle with most?

LB: Oh, making a living.

AF: Really? So it's not an emotional issue or a time issue?

LB: It can become emotional but everybody has a right to make a living from their work. Everybody's right is there. But making art and making a living at art are two completely separate acts, and you've gotta keep 'em separate. But you can't have it become such an issue that it distracts you from your art.

AF: It's a matter of survival, somehow . . .

LB: Yeah. You've gotta somehow learn to walk a rope that's as thin as a spider's web. And at any time you can fall off and at any time it can break. And you know, that's just part of the given of the trip. The main thing is that you try and stay on it and enjoy the walk. Then, everything you see here is nothing more or less than a piece of evidence of a day's activity.

AF: I actually had a question like that, about what is a day in the life of Larry Bell like?