R

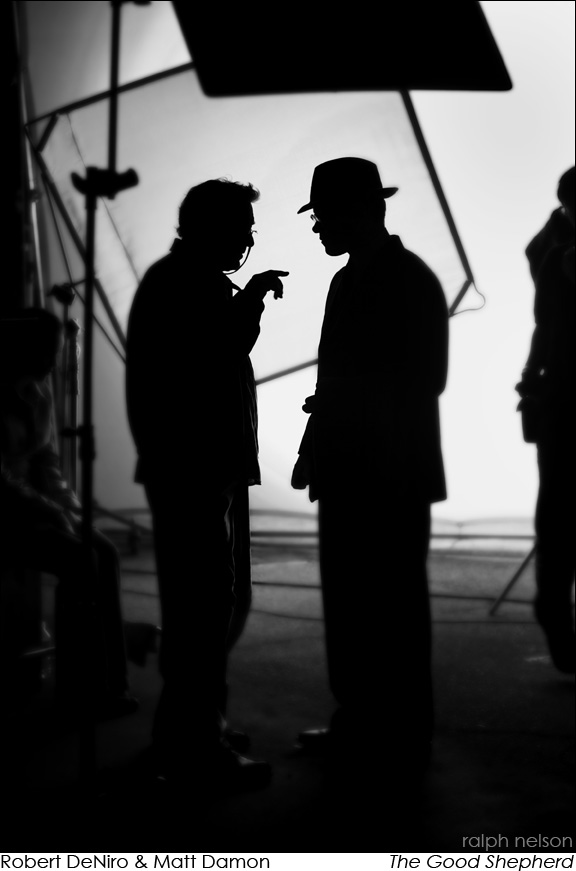

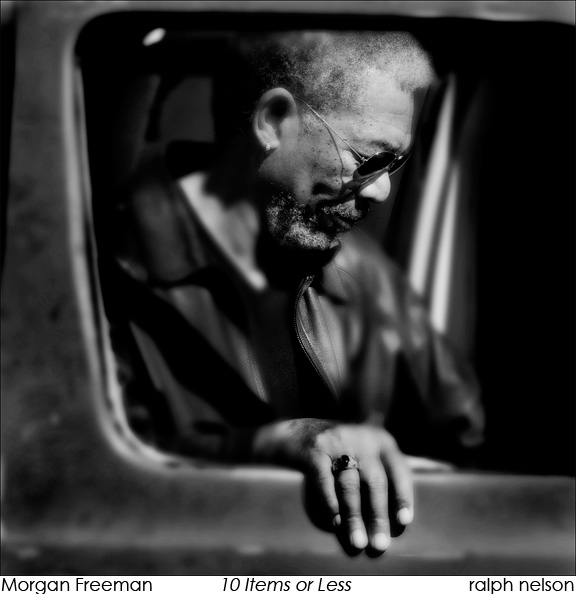

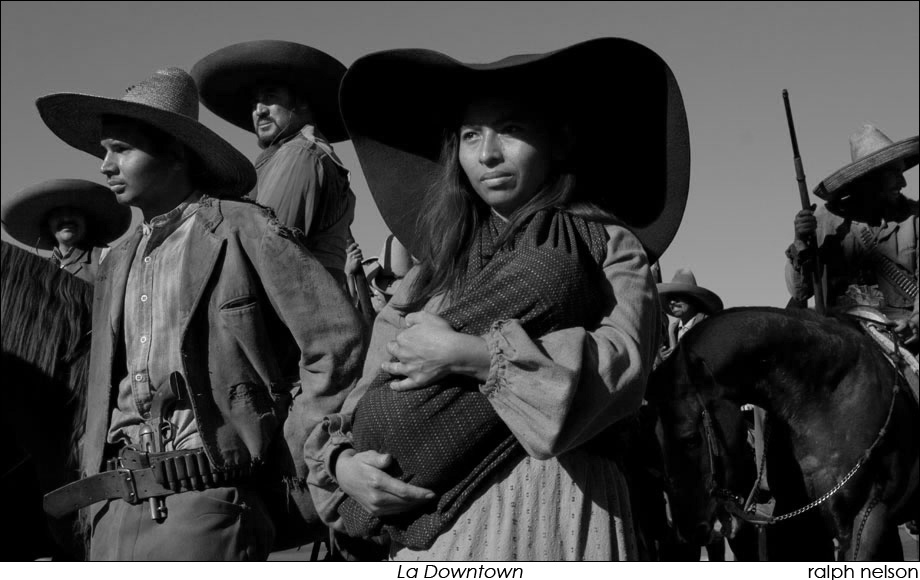

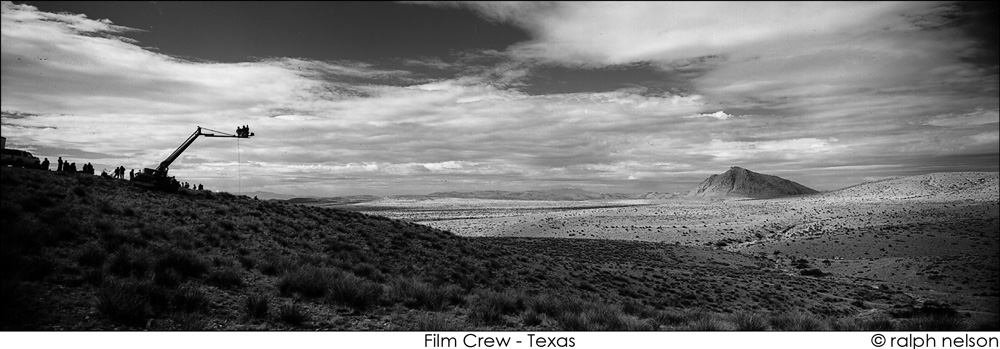

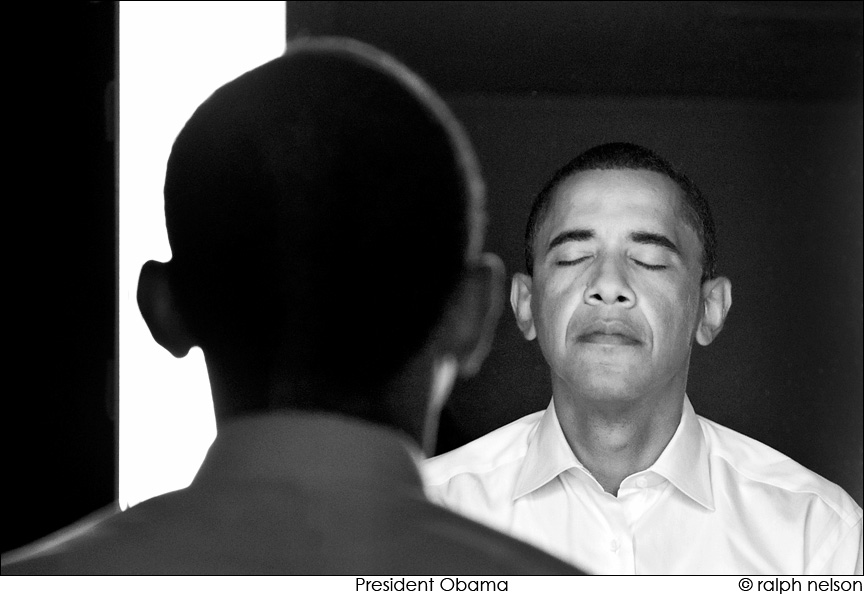

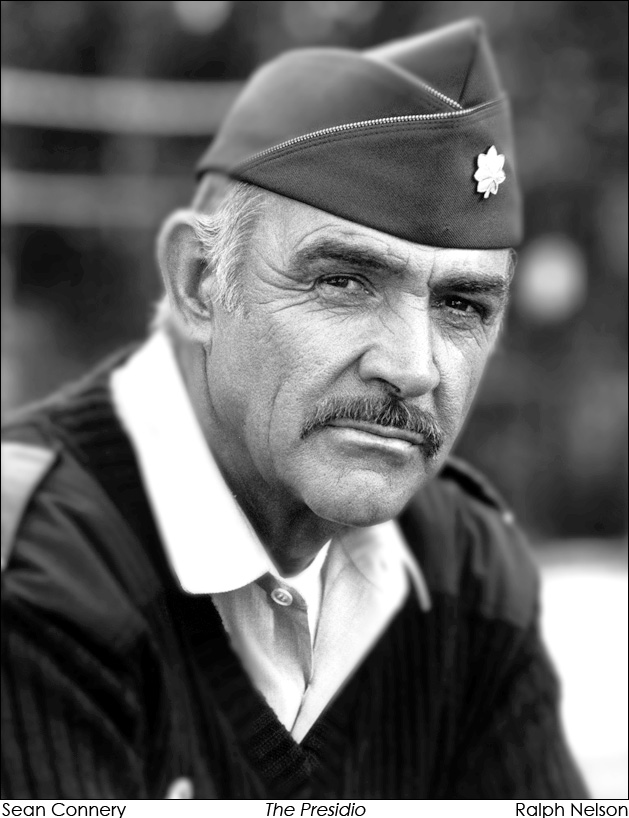

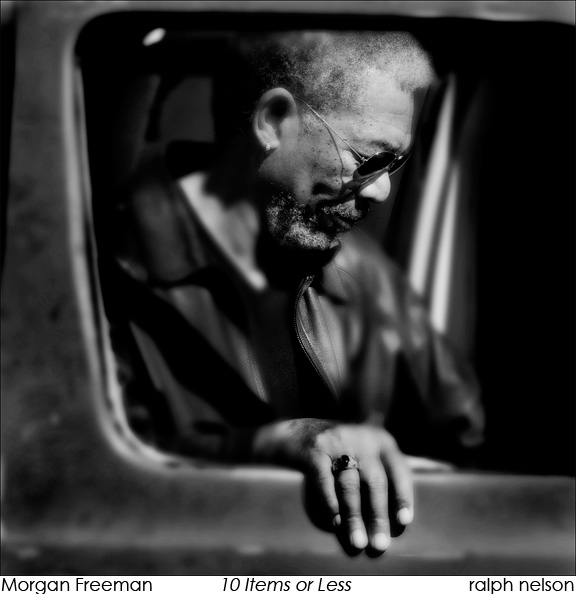

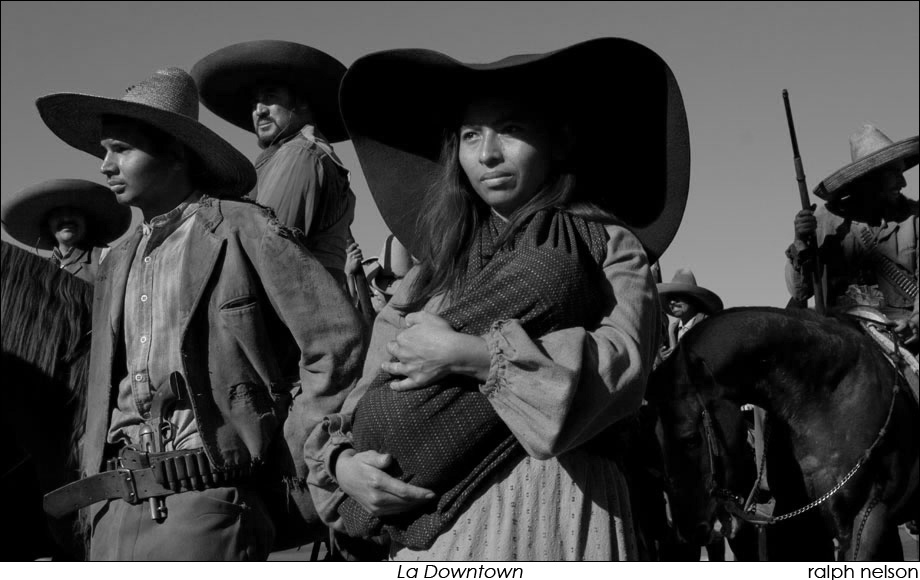

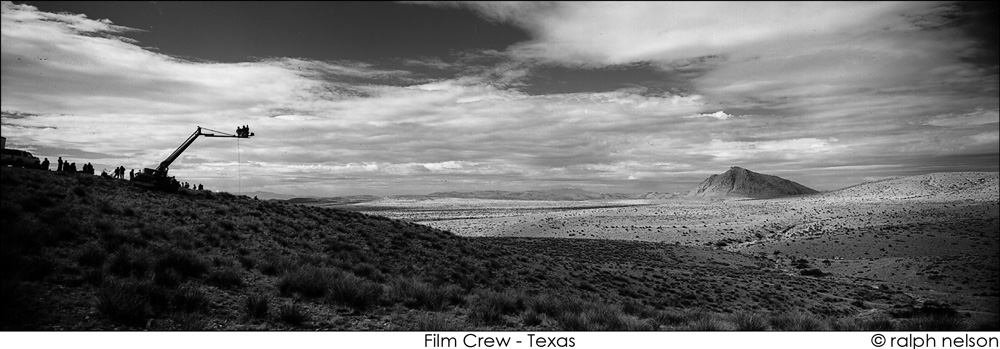

Ralph Nelson is considered one of the finest and most highly respected unit still photographers working today. For those of you who are not familiar with the term, the unit still photographer works on motion pictures. They're on the movie set every day during filming, creating for the studio publicity and advertising departments a key set of stills that will often be used for the entire advertising and publicity campaign of that movie. Their contribution to the whole motion picture process is major, and I can tell you from personal experience, one of the most difficult jobs a professional photographer can ever get themselves into. From the outside, the job appears glamorous and enviable. However, the challenge to produce quality work is enormous. Ralph Nelson is a seasoned veteran. Yet he is very humble about his extraordinary career spanning over thirty-three years. Recently, I interviewed Ralph about his many dedicated years in the motion picture industry and acquired some insights into his vast expertise.

Q. How did you get started in photography?

A. I was inspired by the

Walt Disney True Life Nature series. I imagined myself living in the woods and photographing animals and flowers. So, now I work in films, which pays enough so that in my spare time, I can photograph animals and flowers.

Q. Did you go to school to learn photography?

A. Yes, The Art Center school in Los Angeles, before it moved to Pasadena and upgraded its name to The Art Center College of Design.

Q. Were there any photographers that you felt inspired by back then?

A) Yes - Ernst Haas. I met him on a film set in 1965 and I was later able to assist him on a couple of his

Look magazine assignments.

(AF) What an incredible man! I first met him at Magnum Photos; real gentlemen, I love his book "The Creation".

A. I now often find inspiration in the photos of amateurs whose work may never be widely known. There is an amazing amount of undiscovered and unpublished talent out there and a number of amateurs whom I would happily assist to get a better understanding of how they think and work.

Q. What was your first camera?

A. A Brownie Hawkeye, which sits next to my current cameras, followed by a Rollei given to me by my father in 1963, which was stolen. Oh, you didn't ask about the second one. Never mind.

Q. As I recall from my own experience, Art Center required students to use 4X5 for the first semesters. How did that affect the way you shoot?

A. Shooting sheet film instilled a critical discipline, it made you slow down and pay attention. There is a world of difference between shooting a single large format image and grinding them out with a motor drive. Both have their place, but that discipline was very important.

Q. So those days were obviously only film days; no digital at all. Did you enjoy being in the darkroom?

Q. So those days were obviously only film days; no digital at all. Did you enjoy being in the darkroom?

A. I loved it. The magic of watching an image develop never diminished. Now that I'm out of the darkroom and working on a computer there is a new kind of excitement that comes with the immediacy of digital imaging and the limitless possibilities offered by Photoshop.

Q. What lead you into working as a unit still photographer?

A. It was a natural evolution. I had been working as a freelance journalist when I was chosen to be the first staff photographer for the American Broadcasting Company (ABC). I was at ABC for two years before leaving to do a film. The Hollywood unions were nearly impossible to break into in those days, so I used the only method available to me - nepotism. My father was a producer/director and I logged my required 30 days on one of his films.

Q. How many years have you been working as one?

A. I quit counting when I ran out of toes and fingers. The most recent statement from the Motion Picture Retirement Plan shows 33 years, 57,192.5 hours. After reading that, I thought my next investment should be a burial plot instead of a new camera.

Q. What are the unique challenges you face as a unit still photographer?

A. The change from film to digital.

Q. Can you describe the unique challenges you face in that change?

A. That transition is the modern-day equivalent of the move from horse and buggy to the internal combustion engine. Old world skills are getting lost. Great black and white printers face the same grim reality of the great buggy whip makers.

But I digress. Two challenges for photographers that immediately come to mind are expense and education. We face expenses that did not exist in the pre-digital world; computers, software, peripherals - and far more expensive cameras that need to be updated on about a two-year cycle.

As the equipment improves, so do the studio's expectations. The educational challenge is having a working knowledge of software. New applications are introduced on a regular basis; old ones are updated. A photographer can spend nearly as much time on a computer as he does behind the camera. And a solid understanding of Photoshop is absolutely essential.

Q. Do you think the digital revolution has made it easier or harder on unit still photographers?

A. A bit of both. It is harder because studios expect photographers to have the latest, greatest cameras, which is very costly. Now it can cost tens of thousands of dollars to have sufficient equipment to be fully equipped (digital cameras, computers, software). On the other hand, although I would not say it is easier, digital provides the photographer with opportunities never before available, which if used properly, can help him or her do a better job.

Q. What do you miss about the days when you were shooting film versus digital?

A. Once again, the expense. When I was shooting film, I could buy a new top-of-the-line camera for a few hundred dollars that would last for years. I still have the two Leica M4's that I bought in 1970 for $246 each in Shannon Ireland.

Today the current Leica body is $7,000. Add a lens and you are up to nearly $10,000 for one camera and one lens. Professional cameras cost thousands and newer, bigger, faster, better models are introduced on an ever-shorter cycle. Add to that, the expense of computers and software and in a very short time, you are heavily invested.

Still photographers rent their equipment back to the studios, but at a rate far lower than rental houses. You get the same rate for one camera and lens as you do for cases of equipment. At one time, the rentals were a significant portion of the still photographer's income. Now it barely keeps up with the expense of maintenance and updating both cameras and software.

Q. Reflecting back on the times before digital, when unit photographers were shooting both black & white negative as well as color transparency. Is there anything you miss about that time?

A. No. I'm much happier with digital. Giving up film is like saying goodbye to an old girlfriend. At one time you could not imagine life without her, but now that you have a new love, you are much happier and know that your old flame, though wonderful, could never give you what your new love offers.

Q. Do you read or request to see the script before you take the assignment?

Q. Do you read or request to see the script before you take the assignment?

A. I generally do a quick read-through before production and check the next day's call sheet to make sure there are no surprises. But for the most part, a still photographer should be prepared for anything at all times. My approach is very simple: I just do the best I can with what I'm given. Hopefully, I give the studios what they need. Sometimes I succeed.

Q. What about consulting with the director or others to prepare?

A. Still photographers require less preparation than some other departments. The director is often up to his lips in alligators and faced with a constant onslaught of issues. The studio hires a still photographer knowing (hoping) that he or she knows what is needed and can be relied upon to deliver it consistently.

Q. Do you make an effort to discuss the story points and relationships the actors have with one another with the publicist on the film?

A. No. From your questions, I sense that your approach is somewhat different and that you spend more time in discussion and preparation, which is probably a very smart thing to do.

Q. What about the notion that you're a visitor to the village, meaning they (the studio) literally don't really need you there to make the movie. You're visiting the set; you're photographing the actors doing their scenes, documenting what's going on. You're the only person there who is not involved in making the film.

Does that create a unique set of circumstances in which you have no control? For example, the lighting on the set: you cannot direct the actors yourself or engage in meaningful dialogue with them, pose them, etc. Does that present difficult challenges or frustrating situations for creating excellent stills?

A. It's no different; you make the best of it and do what you can with the light and circumstances you are given.

Q. How would you explain to someone (who is not familiar with what a unit still photographer does) what it is that you do?

A. A typical day is twelve hours, but often much longer. I cover all of the scenes, anything behind the scenes that I think is useful; transfer images from the flash cards to a laptop (MacbookPro), copy them to two other hard drives for backup, make a preliminary edit, throwing away anything that I know can never be used.

At the end of the day, everything is copied to yet another hard drive provided by the lab and it goes to them for processing, renumbering, proofing and distribution.

Q. What do you consider your job to be?

A. Providing photos that will serve the publicity, promotional and advertising needs of the studio.

At one time, the still photographer was also expected to take continuity photos for any number of departments. But as their needs grew, it became impractical for the photographer to do both. Now most hair, makeup, wardrobe, prop - continuity stills - are taken by those departments.

Q. How do you deal with difficult actors - those who hate having their photograph taken, or are uncomfortable with it?

Q. How do you deal with difficult actors - those who hate having their photograph taken, or are uncomfortable with it?

A. There is no one-fits-all solution. If there were, I would patent it and retire. There are any number of reasons that an actor might be uncomfortable; some might find having photos taken to be a distraction; others because they feel they don't look their best. They are the exception, because most are professionals who understand and appreciate the studios needs and go out of their way to be helpful.

Q. When a film wraps, do you make a selection of what you consider to be your best work on a film, the personal choices that you feel are the best photographs?

A. Not that I present to the studio. Their needs are very specific. The guidelines and restrictions that determine what selections are made often have less to do with a great photo than with a need to make a specific point about the characters or the story.

Sometimes they are the same. That brings up another important point - that good photo editors are as important to a photographer's success as a good lab, a fact that is often overlooked.

Q. Do you discuss with the cinematographer what their goals are, in terms of the "look of the picture"?

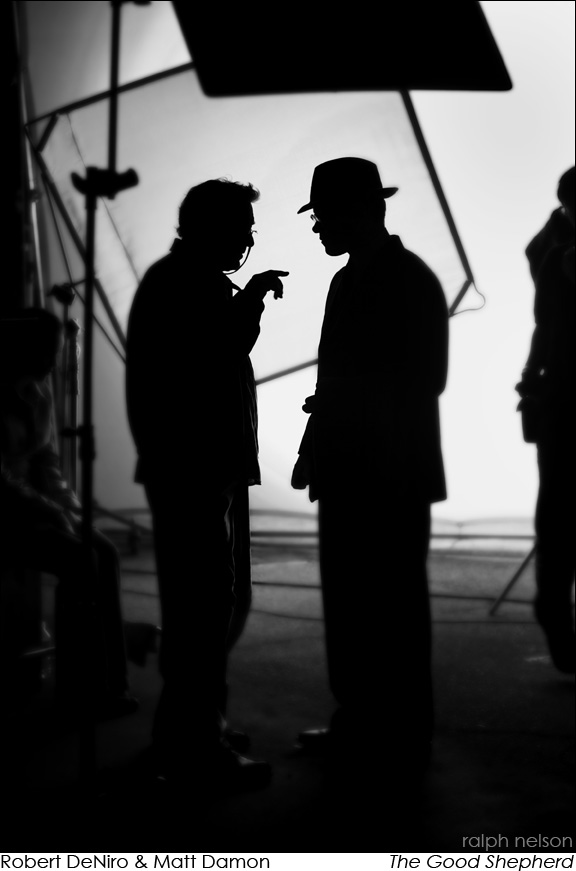

A. No. The cinematographer has a different challenge and our goals are not always the same.

He can have an actor running through the dark in silhouette and it works beautifully. That is because he has the advantage of motion, dialogue, sound effects and background music. A still is presented on a printed page and that same actor running in silhouette against a dark background would be totally useless.

Q. How do you deal with extreme low light levels on the set?

A. With an extremely high ISO and prayer.

Q. Do you customize your digital camera's settings for every scene?

A. Never. Everything is shot RAW. On the other hand, if they ever come up with a custom setting that makes me look like a genius, I'll be all over that one.

Q. Under what circumstances would you request that the actors perform the scene over just for you?

A. There are a number of circumstances.

As an example, going back to your earlier question about actors who do not want their photos taken because they would find my work distracting, I would ask then. Some directors prefer to have the stills shot separately and will make time for the photographer when the scene is completed. It is time consuming (think dollars) and a request that should not be made lightly.

Q. Do you prefer comedies? Heavy drama films? Action pictures?

A. In my early days, I preferred epics and action films. In those days, most of what you saw on screen was shot on a set. Now most action scenes are compilations of elements shot on the set, blue/green screens and digital components.

Now my favorites are those that allow me to get home at night to have dinner with my wife.

Q. What memorable experiences or unusual events have happened to you over the years working on films?

A. The most memorable ones are those that can never be told. Discretion is critical to lasting relationships and a career in film. No one would believe them anyway. I find a few hard to believe myself - and I was there!

Q. Why did you choose feature films instead of television to work on?

A. Features generally had much higher production values, were in exciting distant locations and had a photographer on the set every day. Television was limited by time and budgets and only hired photographers on an "as needed" basis. So television was unreliable for a full-time career.

Q. How do you deal with dangerous situations, for example explosions? Fires? Car chases? The firing of weapons?

A. I look around to find both the best angle for the photo and the safest place to be and I always choose the safe place. Avoiding unnecessary peril is one of the cornerstones of survival.

Q. What do you love most about your job?

A. The people. I can think of no other occupation in which you are surrounded by so many talented people with such diverse interests and skills.

For example, I have a very close friend that I met on Top Gun, a former Blue Angel; another friend from The Green Mile who is a Tennessee mule-skinner (yes it is a real job, look it up!); and another who was raised in Kenya that I've traveled with to Africa and Central America to chase snakes and butterflies. That is just a few examples of the rich diversity of talent and great people who populate film sets.

Q. What do you dislike most about your job?

A. The people. I can think of no other occupation in which you can, on rare occasion, run into such insanely egotistical pompous asses, supported by highly paid teams of sycophants. Thankfully, they are the rare exception.

Q. Do you have a preference, if given the choice, to shoot the rehearsal or the "take"?

A. When possible, I prefer the "take". Generally, that's when all of the elements are in place; the light, wardrobe, makeup, props and most importantly, the performance. Quite often rehearsals are incomplete. Props are not in place; water bottles, scripts and other flotsam are in sight. Makeup, wardrobe and hair may not be camera-ready.

Q. In terms of lighting, do you feel it is important to be next to the movie camera?

A. Camera position has less to do with light than it does with angle. Mark Twain said, "The difference between the almost right word and the right word is the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning." The same holds true for camera angles. Fractions of an inch can make the difference between a compelling photo and a happy-snap.

Q. When production begins, do you make an effort to introduce yourself?

Q. When production begins, do you make an effort to introduce yourself?

A. A typical crew consists of dozens of people on the set and legions more in offices, which often means that in the first week I either introduce myself to the same person several times or worse, fail to introduce myself at all. I'm still working on that one.

Q. How do you ingratiate yourself to the crew?

A. Ingratiate myself? I just show everyone the same respect that I expect in return.

Q. What were some of your favorite films that you have worked on?

A.

Butch & Sundance, the Early Days always comes to mind. Both of my experiences with Francis Ford Coppola,

Tucker and

Dracula. After that, I have to review my credits on IMDb to see what I've done. They all run together. It is easier for me to imagine that I have only worked on just one really, really long film over the past 30+ years. That way, I don't have to remember titles or names.

Q. How important is your relationship with the unit publicist on a film?

A. Very important. There are some great publicists who can be very helpful in making the process work. In recent years, I've worked on a few smaller films that did not have a publicist, which is another sign of the times - cutbacks in below-the-line budgets and staffing. It is a disturbing trend.

Q. How do you deal with "Green Screen" knowing that the final shot in the film will be composited?

A. Like anything else, you do the best you can with what you are given. Those photos can be critical elements for compositing.

Q. How have press kits changed over the years?

A. Traditional press kits with 8X10 prints, 35mm transparencies and press releases are a thing of the past. For a brief time they were replaced by CDs and now even the CDs are being replaced by digital transmission to the end-user. That hasn't had much of an effect on photographers, but it has completely changed the way photo labs do business. Those that have not kept up with the shift to digital are either floundering or have vanished.

Q. As technologies have changed dramatically, specifically digitally, do you believe there will be less need for the still photographer to be on the set?

Q. As technologies have changed dramatically, specifically digitally, do you believe there will be less need for the still photographer to be on the set?

A. Yes, but not because of technology. That's a different issue.

I think it will come from downward pressure on "below the line" labor (if you are not a director, producer or actor, you are below the line). Organized labor in all professions is now working harder and earning less with fewer regulations protecting their interests and safety. The paradigm shift that I predict for motion picture still photographers is that the union rule for "must hire" for feature productions will change to "as needed," as is now done in television.

Q. You really believe that's in the future?

A. I hope I'm wrong, but I think it's in the foreseeable future.

Q. Do you feel any sense of historical responsibility when working on films?

Q. Do you feel any sense of historical responsibility when working on films?

A. Yes, most definitely. Still photographers provide the historical visual record of Hollywood in a way that text cannot. No other industry has as rich a visual history - all created by (drum roll please) the still photographers.

Q. Do you photograph the entire crew?

A. Most attention is paid to the director, actors and producers. Following close behind would be department heads, who have a significant impact on the look of a film. Keep in mind that there are hundreds of people involved and many of them never come near the set. (Have you ever tried to read all of the credits at the end?) So it would be impossible to cover them all.

Q. How much do you let the approval process affect you? [Note: all photographs must go through a rigorous approval process by all actors and studio representatives]

A. Not at all. I do the best I can and have no emotional attachment to most of the work

Q. You don't get upset when you think you've done some great work and it doesn't get approved?

A. No, not at all

Q. Really? Is that because you've just become jaded over the years?

A. Not jaded; just realistic. Many of my best photos have never seen the light of day and never will. Other, more pedestrian work, gets published on a regular basis.

The studio's needs are specific and pretty pictures that don't fill those needs are of little value. That should not affect the way you shoot. Sometimes those photos are used. Sometimes, they are not. I am not emotionally attached.

Q. Film shoots have notoriously long workdays. What was your longest?

A. There have been a number of films that went over 20 hours. A twelve-hour day is considered short. And now, with the elimination of a number of union rules protecting workers, twelve is often only the beginning. It is a dangerous trend that has resulted in deadly accidents. Everyone in the business has stories of having fallen asleep at the wheel while driving home. I fell asleep and drove though a concrete wall on San Vicente very early in the morning after a full week of insanely long days. Our director also ran off the road on the same day. So our hours were trimmed a bit. Others have not been as lucky and have been killed.

Q. Have you ever turned a movie down because you didn't like the screenplay? And if so, for what reason?

A. Yes. There have been a few that were just vulgar that were easy to say "no" to. In recent years I've turned down a number because they would have kept me away from home for too long.

Q. I have an important question (laughter). Do you have a movie you want to direct?

A. No. Maybe someday, if I ever feel that I have finally mastered my craft, I will give thought to directing or brain surgery, each of which I am equally unqualified. That has not happened yet.

Q

. Are there any final thoughts that you would like to share with photographers who are considering getting into motion picture stills?

A. Yes. The Boy Scout motto says it best: "Be Prepared." Do not come to the party until you have some solid experience behind you, the necessary equipment and the knowledge. And if you have an ego, leave it at home. I could go on and on, but I'm sure there is a limit to your patience.

Oh and one more thing - and this is very important. If you want to get into motion picture stills so you can hang around Hollywood, rub elbows with the stars, stroll down red carpets and wear sunglasses, move on, there is nothing for you here.

Q. So lets completely switch gears here and talk about you personal work. Tell me a little bit about that. What have you been doing? What have you been photographing?

A. Like you, I seldom go out without a camera. Invariably, I regret it when I do.

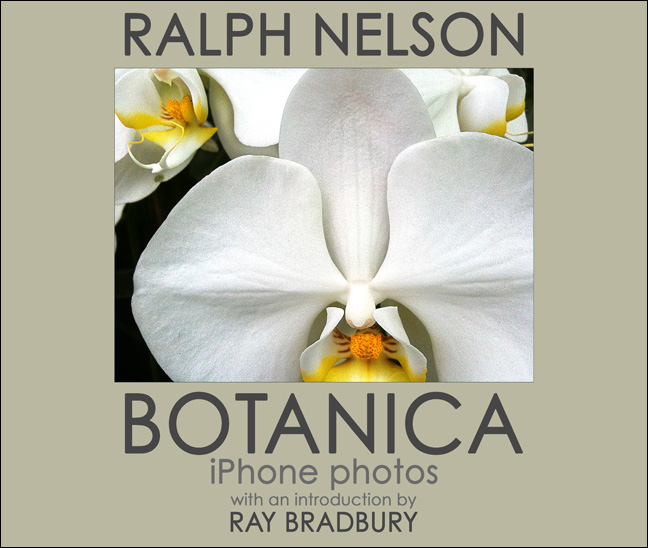

Recently, I took a photo of a flower with the iPhone and I was surprised at the results. I had been using it to make visual notes, but never thought about it's potential as a "real" camera. The flower photo was good enough to make me wonder what I could do with it, so I gave myself two weeks to shoot only with the iPhone, which meant no control over the exposure, no lens choices, no control of any sort, except for framing the image. To maintain the purist approach, I also restricted myself; no cropping or image manipulation other than contrast and sharpening in Photoshop.

I was both stunned and thrilled with the results. I'm now putting together a book and Ray Bradbury has written an introduction. The iPhone is not going to replace cameras for work, but it offers some very interesting possibilities that I look forward to exploring further.

Now if you are finished, I have a question for you:

Yes?

Are we going to have a glass of wine now? It must be cocktail hour somewhere on the planet and all this talk makes me thirsty.

Ralph Nelson is considered one of the finest and most highly respected unit still photographers working today. For those of you who are not familiar with the term, the unit still photographer works on motion pictures. They're on the movie set every day during filming, creating for the studio publicity and advertising departments a key set of stills that will often be used for the entire advertising and publicity campaign of that movie. Their contribution to the whole motion picture process is major, and I can tell you from personal experience, one of the most difficult jobs a professional photographer can ever get themselves into. From the outside, the job appears glamorous and enviable. However, the challenge to produce quality work is enormous. Ralph Nelson is a seasoned veteran. Yet he is very humble about his extraordinary career spanning over thirty-three years. Recently, I interviewed Ralph about his many dedicated years in the motion picture industry and acquired some insights into his vast expertise.

Q. How did you get started in photography?

A. I was inspired by the Walt Disney True Life Nature series. I imagined myself living in the woods and photographing animals and flowers. So, now I work in films, which pays enough so that in my spare time, I can photograph animals and flowers.

Q. Did you go to school to learn photography?

A. Yes, The Art Center school in Los Angeles, before it moved to Pasadena and upgraded its name to The Art Center College of Design.

Q. Were there any photographers that you felt inspired by back then?

Ralph Nelson is considered one of the finest and most highly respected unit still photographers working today. For those of you who are not familiar with the term, the unit still photographer works on motion pictures. They're on the movie set every day during filming, creating for the studio publicity and advertising departments a key set of stills that will often be used for the entire advertising and publicity campaign of that movie. Their contribution to the whole motion picture process is major, and I can tell you from personal experience, one of the most difficult jobs a professional photographer can ever get themselves into. From the outside, the job appears glamorous and enviable. However, the challenge to produce quality work is enormous. Ralph Nelson is a seasoned veteran. Yet he is very humble about his extraordinary career spanning over thirty-three years. Recently, I interviewed Ralph about his many dedicated years in the motion picture industry and acquired some insights into his vast expertise.

Q. How did you get started in photography?

A. I was inspired by the Walt Disney True Life Nature series. I imagined myself living in the woods and photographing animals and flowers. So, now I work in films, which pays enough so that in my spare time, I can photograph animals and flowers.

Q. Did you go to school to learn photography?

A. Yes, The Art Center school in Los Angeles, before it moved to Pasadena and upgraded its name to The Art Center College of Design.

Q. Were there any photographers that you felt inspired by back then? A) Yes - Ernst Haas. I met him on a film set in 1965 and I was later able to assist him on a couple of his Look magazine assignments.

(AF) What an incredible man! I first met him at Magnum Photos; real gentlemen, I love his book "The Creation".

A. I now often find inspiration in the photos of amateurs whose work may never be widely known. There is an amazing amount of undiscovered and unpublished talent out there and a number of amateurs whom I would happily assist to get a better understanding of how they think and work.

Q. What was your first camera?

A. A Brownie Hawkeye, which sits next to my current cameras, followed by a Rollei given to me by my father in 1963, which was stolen. Oh, you didn't ask about the second one. Never mind.

Q. As I recall from my own experience, Art Center required students to use 4X5 for the first semesters. How did that affect the way you shoot?

A. Shooting sheet film instilled a critical discipline, it made you slow down and pay attention. There is a world of difference between shooting a single large format image and grinding them out with a motor drive. Both have their place, but that discipline was very important.

A) Yes - Ernst Haas. I met him on a film set in 1965 and I was later able to assist him on a couple of his Look magazine assignments.

(AF) What an incredible man! I first met him at Magnum Photos; real gentlemen, I love his book "The Creation".

A. I now often find inspiration in the photos of amateurs whose work may never be widely known. There is an amazing amount of undiscovered and unpublished talent out there and a number of amateurs whom I would happily assist to get a better understanding of how they think and work.

Q. What was your first camera?

A. A Brownie Hawkeye, which sits next to my current cameras, followed by a Rollei given to me by my father in 1963, which was stolen. Oh, you didn't ask about the second one. Never mind.

Q. As I recall from my own experience, Art Center required students to use 4X5 for the first semesters. How did that affect the way you shoot?

A. Shooting sheet film instilled a critical discipline, it made you slow down and pay attention. There is a world of difference between shooting a single large format image and grinding them out with a motor drive. Both have their place, but that discipline was very important.

Q. So those days were obviously only film days; no digital at all. Did you enjoy being in the darkroom?

A. I loved it. The magic of watching an image develop never diminished. Now that I'm out of the darkroom and working on a computer there is a new kind of excitement that comes with the immediacy of digital imaging and the limitless possibilities offered by Photoshop.

Q. What lead you into working as a unit still photographer?

A. It was a natural evolution. I had been working as a freelance journalist when I was chosen to be the first staff photographer for the American Broadcasting Company (ABC). I was at ABC for two years before leaving to do a film. The Hollywood unions were nearly impossible to break into in those days, so I used the only method available to me - nepotism. My father was a producer/director and I logged my required 30 days on one of his films.

Q. How many years have you been working as one?

A. I quit counting when I ran out of toes and fingers. The most recent statement from the Motion Picture Retirement Plan shows 33 years, 57,192.5 hours. After reading that, I thought my next investment should be a burial plot instead of a new camera.

Q. What are the unique challenges you face as a unit still photographer?

A. The change from film to digital.

Q. Can you describe the unique challenges you face in that change?

A. That transition is the modern-day equivalent of the move from horse and buggy to the internal combustion engine. Old world skills are getting lost. Great black and white printers face the same grim reality of the great buggy whip makers.

But I digress. Two challenges for photographers that immediately come to mind are expense and education. We face expenses that did not exist in the pre-digital world; computers, software, peripherals - and far more expensive cameras that need to be updated on about a two-year cycle.

Q. So those days were obviously only film days; no digital at all. Did you enjoy being in the darkroom?

A. I loved it. The magic of watching an image develop never diminished. Now that I'm out of the darkroom and working on a computer there is a new kind of excitement that comes with the immediacy of digital imaging and the limitless possibilities offered by Photoshop.

Q. What lead you into working as a unit still photographer?

A. It was a natural evolution. I had been working as a freelance journalist when I was chosen to be the first staff photographer for the American Broadcasting Company (ABC). I was at ABC for two years before leaving to do a film. The Hollywood unions were nearly impossible to break into in those days, so I used the only method available to me - nepotism. My father was a producer/director and I logged my required 30 days on one of his films.

Q. How many years have you been working as one?

A. I quit counting when I ran out of toes and fingers. The most recent statement from the Motion Picture Retirement Plan shows 33 years, 57,192.5 hours. After reading that, I thought my next investment should be a burial plot instead of a new camera.

Q. What are the unique challenges you face as a unit still photographer?

A. The change from film to digital.

Q. Can you describe the unique challenges you face in that change?

A. That transition is the modern-day equivalent of the move from horse and buggy to the internal combustion engine. Old world skills are getting lost. Great black and white printers face the same grim reality of the great buggy whip makers.

But I digress. Two challenges for photographers that immediately come to mind are expense and education. We face expenses that did not exist in the pre-digital world; computers, software, peripherals - and far more expensive cameras that need to be updated on about a two-year cycle. As the equipment improves, so do the studio's expectations. The educational challenge is having a working knowledge of software. New applications are introduced on a regular basis; old ones are updated. A photographer can spend nearly as much time on a computer as he does behind the camera. And a solid understanding of Photoshop is absolutely essential.

Q. Do you think the digital revolution has made it easier or harder on unit still photographers?

A. A bit of both. It is harder because studios expect photographers to have the latest, greatest cameras, which is very costly. Now it can cost tens of thousands of dollars to have sufficient equipment to be fully equipped (digital cameras, computers, software). On the other hand, although I would not say it is easier, digital provides the photographer with opportunities never before available, which if used properly, can help him or her do a better job.

Q. What do you miss about the days when you were shooting film versus digital?

A. Once again, the expense. When I was shooting film, I could buy a new top-of-the-line camera for a few hundred dollars that would last for years. I still have the two Leica M4's that I bought in 1970 for $246 each in Shannon Ireland.

Today the current Leica body is $7,000. Add a lens and you are up to nearly $10,000 for one camera and one lens. Professional cameras cost thousands and newer, bigger, faster, better models are introduced on an ever-shorter cycle. Add to that, the expense of computers and software and in a very short time, you are heavily invested.

Still photographers rent their equipment back to the studios, but at a rate far lower than rental houses. You get the same rate for one camera and lens as you do for cases of equipment. At one time, the rentals were a significant portion of the still photographer's income. Now it barely keeps up with the expense of maintenance and updating both cameras and software.

Q. Reflecting back on the times before digital, when unit photographers were shooting both black & white negative as well as color transparency. Is there anything you miss about that time?

A. No. I'm much happier with digital. Giving up film is like saying goodbye to an old girlfriend. At one time you could not imagine life without her, but now that you have a new love, you are much happier and know that your old flame, though wonderful, could never give you what your new love offers.

As the equipment improves, so do the studio's expectations. The educational challenge is having a working knowledge of software. New applications are introduced on a regular basis; old ones are updated. A photographer can spend nearly as much time on a computer as he does behind the camera. And a solid understanding of Photoshop is absolutely essential.

Q. Do you think the digital revolution has made it easier or harder on unit still photographers?

A. A bit of both. It is harder because studios expect photographers to have the latest, greatest cameras, which is very costly. Now it can cost tens of thousands of dollars to have sufficient equipment to be fully equipped (digital cameras, computers, software). On the other hand, although I would not say it is easier, digital provides the photographer with opportunities never before available, which if used properly, can help him or her do a better job.

Q. What do you miss about the days when you were shooting film versus digital?

A. Once again, the expense. When I was shooting film, I could buy a new top-of-the-line camera for a few hundred dollars that would last for years. I still have the two Leica M4's that I bought in 1970 for $246 each in Shannon Ireland.

Today the current Leica body is $7,000. Add a lens and you are up to nearly $10,000 for one camera and one lens. Professional cameras cost thousands and newer, bigger, faster, better models are introduced on an ever-shorter cycle. Add to that, the expense of computers and software and in a very short time, you are heavily invested.

Still photographers rent their equipment back to the studios, but at a rate far lower than rental houses. You get the same rate for one camera and lens as you do for cases of equipment. At one time, the rentals were a significant portion of the still photographer's income. Now it barely keeps up with the expense of maintenance and updating both cameras and software.

Q. Reflecting back on the times before digital, when unit photographers were shooting both black & white negative as well as color transparency. Is there anything you miss about that time?

A. No. I'm much happier with digital. Giving up film is like saying goodbye to an old girlfriend. At one time you could not imagine life without her, but now that you have a new love, you are much happier and know that your old flame, though wonderful, could never give you what your new love offers.

Q. Do you read or request to see the script before you take the assignment?

A. I generally do a quick read-through before production and check the next day's call sheet to make sure there are no surprises. But for the most part, a still photographer should be prepared for anything at all times. My approach is very simple: I just do the best I can with what I'm given. Hopefully, I give the studios what they need. Sometimes I succeed.

Q. What about consulting with the director or others to prepare?

A. Still photographers require less preparation than some other departments. The director is often up to his lips in alligators and faced with a constant onslaught of issues. The studio hires a still photographer knowing (hoping) that he or she knows what is needed and can be relied upon to deliver it consistently.

Q. Do you make an effort to discuss the story points and relationships the actors have with one another with the publicist on the film?

A. No. From your questions, I sense that your approach is somewhat different and that you spend more time in discussion and preparation, which is probably a very smart thing to do.

Q. What about the notion that you're a visitor to the village, meaning they (the studio) literally don't really need you there to make the movie. You're visiting the set; you're photographing the actors doing their scenes, documenting what's going on. You're the only person there who is not involved in making the film.

Does that create a unique set of circumstances in which you have no control? For example, the lighting on the set: you cannot direct the actors yourself or engage in meaningful dialogue with them, pose them, etc. Does that present difficult challenges or frustrating situations for creating excellent stills?

A. It's no different; you make the best of it and do what you can with the light and circumstances you are given.

Q. How would you explain to someone (who is not familiar with what a unit still photographer does) what it is that you do?

A. A typical day is twelve hours, but often much longer. I cover all of the scenes, anything behind the scenes that I think is useful; transfer images from the flash cards to a laptop (MacbookPro), copy them to two other hard drives for backup, make a preliminary edit, throwing away anything that I know can never be used.

At the end of the day, everything is copied to yet another hard drive provided by the lab and it goes to them for processing, renumbering, proofing and distribution.

Q. What do you consider your job to be?

A. Providing photos that will serve the publicity, promotional and advertising needs of the studio.

At one time, the still photographer was also expected to take continuity photos for any number of departments. But as their needs grew, it became impractical for the photographer to do both. Now most hair, makeup, wardrobe, prop - continuity stills - are taken by those departments.

Q. Do you read or request to see the script before you take the assignment?

A. I generally do a quick read-through before production and check the next day's call sheet to make sure there are no surprises. But for the most part, a still photographer should be prepared for anything at all times. My approach is very simple: I just do the best I can with what I'm given. Hopefully, I give the studios what they need. Sometimes I succeed.

Q. What about consulting with the director or others to prepare?

A. Still photographers require less preparation than some other departments. The director is often up to his lips in alligators and faced with a constant onslaught of issues. The studio hires a still photographer knowing (hoping) that he or she knows what is needed and can be relied upon to deliver it consistently.

Q. Do you make an effort to discuss the story points and relationships the actors have with one another with the publicist on the film?

A. No. From your questions, I sense that your approach is somewhat different and that you spend more time in discussion and preparation, which is probably a very smart thing to do.

Q. What about the notion that you're a visitor to the village, meaning they (the studio) literally don't really need you there to make the movie. You're visiting the set; you're photographing the actors doing their scenes, documenting what's going on. You're the only person there who is not involved in making the film.

Does that create a unique set of circumstances in which you have no control? For example, the lighting on the set: you cannot direct the actors yourself or engage in meaningful dialogue with them, pose them, etc. Does that present difficult challenges or frustrating situations for creating excellent stills?

A. It's no different; you make the best of it and do what you can with the light and circumstances you are given.

Q. How would you explain to someone (who is not familiar with what a unit still photographer does) what it is that you do?

A. A typical day is twelve hours, but often much longer. I cover all of the scenes, anything behind the scenes that I think is useful; transfer images from the flash cards to a laptop (MacbookPro), copy them to two other hard drives for backup, make a preliminary edit, throwing away anything that I know can never be used.

At the end of the day, everything is copied to yet another hard drive provided by the lab and it goes to them for processing, renumbering, proofing and distribution.

Q. What do you consider your job to be?

A. Providing photos that will serve the publicity, promotional and advertising needs of the studio.

At one time, the still photographer was also expected to take continuity photos for any number of departments. But as their needs grew, it became impractical for the photographer to do both. Now most hair, makeup, wardrobe, prop - continuity stills - are taken by those departments.

Q. How do you deal with difficult actors - those who hate having their photograph taken, or are uncomfortable with it?

A. There is no one-fits-all solution. If there were, I would patent it and retire. There are any number of reasons that an actor might be uncomfortable; some might find having photos taken to be a distraction; others because they feel they don't look their best. They are the exception, because most are professionals who understand and appreciate the studios needs and go out of their way to be helpful.

Q. When a film wraps, do you make a selection of what you consider to be your best work on a film, the personal choices that you feel are the best photographs?

A. Not that I present to the studio. Their needs are very specific. The guidelines and restrictions that determine what selections are made often have less to do with a great photo than with a need to make a specific point about the characters or the story.

Sometimes they are the same. That brings up another important point - that good photo editors are as important to a photographer's success as a good lab, a fact that is often overlooked.

Q. Do you discuss with the cinematographer what their goals are, in terms of the "look of the picture"?

A. No. The cinematographer has a different challenge and our goals are not always the same.

He can have an actor running through the dark in silhouette and it works beautifully. That is because he has the advantage of motion, dialogue, sound effects and background music. A still is presented on a printed page and that same actor running in silhouette against a dark background would be totally useless.

Q. How do you deal with extreme low light levels on the set?

A. With an extremely high ISO and prayer.

Q. Do you customize your digital camera's settings for every scene?

A. Never. Everything is shot RAW. On the other hand, if they ever come up with a custom setting that makes me look like a genius, I'll be all over that one.

Q. Under what circumstances would you request that the actors perform the scene over just for you?

A. There are a number of circumstances.

As an example, going back to your earlier question about actors who do not want their photos taken because they would find my work distracting, I would ask then. Some directors prefer to have the stills shot separately and will make time for the photographer when the scene is completed. It is time consuming (think dollars) and a request that should not be made lightly.

Q. Do you prefer comedies? Heavy drama films? Action pictures?

A. In my early days, I preferred epics and action films. In those days, most of what you saw on screen was shot on a set. Now most action scenes are compilations of elements shot on the set, blue/green screens and digital components.

Q. How do you deal with difficult actors - those who hate having their photograph taken, or are uncomfortable with it?

A. There is no one-fits-all solution. If there were, I would patent it and retire. There are any number of reasons that an actor might be uncomfortable; some might find having photos taken to be a distraction; others because they feel they don't look their best. They are the exception, because most are professionals who understand and appreciate the studios needs and go out of their way to be helpful.

Q. When a film wraps, do you make a selection of what you consider to be your best work on a film, the personal choices that you feel are the best photographs?

A. Not that I present to the studio. Their needs are very specific. The guidelines and restrictions that determine what selections are made often have less to do with a great photo than with a need to make a specific point about the characters or the story.

Sometimes they are the same. That brings up another important point - that good photo editors are as important to a photographer's success as a good lab, a fact that is often overlooked.

Q. Do you discuss with the cinematographer what their goals are, in terms of the "look of the picture"?

A. No. The cinematographer has a different challenge and our goals are not always the same.

He can have an actor running through the dark in silhouette and it works beautifully. That is because he has the advantage of motion, dialogue, sound effects and background music. A still is presented on a printed page and that same actor running in silhouette against a dark background would be totally useless.

Q. How do you deal with extreme low light levels on the set?

A. With an extremely high ISO and prayer.

Q. Do you customize your digital camera's settings for every scene?

A. Never. Everything is shot RAW. On the other hand, if they ever come up with a custom setting that makes me look like a genius, I'll be all over that one.

Q. Under what circumstances would you request that the actors perform the scene over just for you?

A. There are a number of circumstances.

As an example, going back to your earlier question about actors who do not want their photos taken because they would find my work distracting, I would ask then. Some directors prefer to have the stills shot separately and will make time for the photographer when the scene is completed. It is time consuming (think dollars) and a request that should not be made lightly.

Q. Do you prefer comedies? Heavy drama films? Action pictures?

A. In my early days, I preferred epics and action films. In those days, most of what you saw on screen was shot on a set. Now most action scenes are compilations of elements shot on the set, blue/green screens and digital components.

Now my favorites are those that allow me to get home at night to have dinner with my wife.

Q. What memorable experiences or unusual events have happened to you over the years working on films?

A. The most memorable ones are those that can never be told. Discretion is critical to lasting relationships and a career in film. No one would believe them anyway. I find a few hard to believe myself - and I was there!

Q. Why did you choose feature films instead of television to work on?

A. Features generally had much higher production values, were in exciting distant locations and had a photographer on the set every day. Television was limited by time and budgets and only hired photographers on an "as needed" basis. So television was unreliable for a full-time career.

Q. How do you deal with dangerous situations, for example explosions? Fires? Car chases? The firing of weapons?

A. I look around to find both the best angle for the photo and the safest place to be and I always choose the safe place. Avoiding unnecessary peril is one of the cornerstones of survival.

Q. What do you love most about your job?

Now my favorites are those that allow me to get home at night to have dinner with my wife.

Q. What memorable experiences or unusual events have happened to you over the years working on films?

A. The most memorable ones are those that can never be told. Discretion is critical to lasting relationships and a career in film. No one would believe them anyway. I find a few hard to believe myself - and I was there!

Q. Why did you choose feature films instead of television to work on?

A. Features generally had much higher production values, were in exciting distant locations and had a photographer on the set every day. Television was limited by time and budgets and only hired photographers on an "as needed" basis. So television was unreliable for a full-time career.

Q. How do you deal with dangerous situations, for example explosions? Fires? Car chases? The firing of weapons?

A. I look around to find both the best angle for the photo and the safest place to be and I always choose the safe place. Avoiding unnecessary peril is one of the cornerstones of survival.

Q. What do you love most about your job? A. The people. I can think of no other occupation in which you are surrounded by so many talented people with such diverse interests and skills.

For example, I have a very close friend that I met on Top Gun, a former Blue Angel; another friend from The Green Mile who is a Tennessee mule-skinner (yes it is a real job, look it up!); and another who was raised in Kenya that I've traveled with to Africa and Central America to chase snakes and butterflies. That is just a few examples of the rich diversity of talent and great people who populate film sets.

Q. What do you dislike most about your job?

A. The people. I can think of no other occupation in which you can, on rare occasion, run into such insanely egotistical pompous asses, supported by highly paid teams of sycophants. Thankfully, they are the rare exception.

Q. Do you have a preference, if given the choice, to shoot the rehearsal or the "take"?

A. When possible, I prefer the "take". Generally, that's when all of the elements are in place; the light, wardrobe, makeup, props and most importantly, the performance. Quite often rehearsals are incomplete. Props are not in place; water bottles, scripts and other flotsam are in sight. Makeup, wardrobe and hair may not be camera-ready.

Q. In terms of lighting, do you feel it is important to be next to the movie camera?

A. Camera position has less to do with light than it does with angle. Mark Twain said, "The difference between the almost right word and the right word is the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning." The same holds true for camera angles. Fractions of an inch can make the difference between a compelling photo and a happy-snap.

A. The people. I can think of no other occupation in which you are surrounded by so many talented people with such diverse interests and skills.

For example, I have a very close friend that I met on Top Gun, a former Blue Angel; another friend from The Green Mile who is a Tennessee mule-skinner (yes it is a real job, look it up!); and another who was raised in Kenya that I've traveled with to Africa and Central America to chase snakes and butterflies. That is just a few examples of the rich diversity of talent and great people who populate film sets.

Q. What do you dislike most about your job?

A. The people. I can think of no other occupation in which you can, on rare occasion, run into such insanely egotistical pompous asses, supported by highly paid teams of sycophants. Thankfully, they are the rare exception.

Q. Do you have a preference, if given the choice, to shoot the rehearsal or the "take"?

A. When possible, I prefer the "take". Generally, that's when all of the elements are in place; the light, wardrobe, makeup, props and most importantly, the performance. Quite often rehearsals are incomplete. Props are not in place; water bottles, scripts and other flotsam are in sight. Makeup, wardrobe and hair may not be camera-ready.

Q. In terms of lighting, do you feel it is important to be next to the movie camera?

A. Camera position has less to do with light than it does with angle. Mark Twain said, "The difference between the almost right word and the right word is the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning." The same holds true for camera angles. Fractions of an inch can make the difference between a compelling photo and a happy-snap.

Q. When production begins, do you make an effort to introduce yourself?

A. A typical crew consists of dozens of people on the set and legions more in offices, which often means that in the first week I either introduce myself to the same person several times or worse, fail to introduce myself at all. I'm still working on that one.

Q. How do you ingratiate yourself to the crew?

A. Ingratiate myself? I just show everyone the same respect that I expect in return.

Q. What were some of your favorite films that you have worked on?

A. Butch & Sundance, the Early Days always comes to mind. Both of my experiences with Francis Ford Coppola, Tucker and Dracula. After that, I have to review my credits on IMDb to see what I've done. They all run together. It is easier for me to imagine that I have only worked on just one really, really long film over the past 30+ years. That way, I don't have to remember titles or names.

Q. How important is your relationship with the unit publicist on a film?

A. Very important. There are some great publicists who can be very helpful in making the process work. In recent years, I've worked on a few smaller films that did not have a publicist, which is another sign of the times - cutbacks in below-the-line budgets and staffing. It is a disturbing trend.

Q. How do you deal with "Green Screen" knowing that the final shot in the film will be composited?

A. Like anything else, you do the best you can with what you are given. Those photos can be critical elements for compositing.

Q. How have press kits changed over the years?

A. Traditional press kits with 8X10 prints, 35mm transparencies and press releases are a thing of the past. For a brief time they were replaced by CDs and now even the CDs are being replaced by digital transmission to the end-user. That hasn't had much of an effect on photographers, but it has completely changed the way photo labs do business. Those that have not kept up with the shift to digital are either floundering or have vanished.

Q. When production begins, do you make an effort to introduce yourself?

A. A typical crew consists of dozens of people on the set and legions more in offices, which often means that in the first week I either introduce myself to the same person several times or worse, fail to introduce myself at all. I'm still working on that one.

Q. How do you ingratiate yourself to the crew?

A. Ingratiate myself? I just show everyone the same respect that I expect in return.

Q. What were some of your favorite films that you have worked on?

A. Butch & Sundance, the Early Days always comes to mind. Both of my experiences with Francis Ford Coppola, Tucker and Dracula. After that, I have to review my credits on IMDb to see what I've done. They all run together. It is easier for me to imagine that I have only worked on just one really, really long film over the past 30+ years. That way, I don't have to remember titles or names.

Q. How important is your relationship with the unit publicist on a film?

A. Very important. There are some great publicists who can be very helpful in making the process work. In recent years, I've worked on a few smaller films that did not have a publicist, which is another sign of the times - cutbacks in below-the-line budgets and staffing. It is a disturbing trend.

Q. How do you deal with "Green Screen" knowing that the final shot in the film will be composited?

A. Like anything else, you do the best you can with what you are given. Those photos can be critical elements for compositing.

Q. How have press kits changed over the years?

A. Traditional press kits with 8X10 prints, 35mm transparencies and press releases are a thing of the past. For a brief time they were replaced by CDs and now even the CDs are being replaced by digital transmission to the end-user. That hasn't had much of an effect on photographers, but it has completely changed the way photo labs do business. Those that have not kept up with the shift to digital are either floundering or have vanished. Q. As technologies have changed dramatically, specifically digitally, do you believe there will be less need for the still photographer to be on the set?

A. Yes, but not because of technology. That's a different issue.

I think it will come from downward pressure on "below the line" labor (if you are not a director, producer or actor, you are below the line). Organized labor in all professions is now working harder and earning less with fewer regulations protecting their interests and safety. The paradigm shift that I predict for motion picture still photographers is that the union rule for "must hire" for feature productions will change to "as needed," as is now done in television.

Q. You really believe that's in the future?

A. I hope I'm wrong, but I think it's in the foreseeable future.

Q. As technologies have changed dramatically, specifically digitally, do you believe there will be less need for the still photographer to be on the set?

A. Yes, but not because of technology. That's a different issue.

I think it will come from downward pressure on "below the line" labor (if you are not a director, producer or actor, you are below the line). Organized labor in all professions is now working harder and earning less with fewer regulations protecting their interests and safety. The paradigm shift that I predict for motion picture still photographers is that the union rule for "must hire" for feature productions will change to "as needed," as is now done in television.

Q. You really believe that's in the future?

A. I hope I'm wrong, but I think it's in the foreseeable future.

Q. Do you feel any sense of historical responsibility when working on films?

A. Yes, most definitely. Still photographers provide the historical visual record of Hollywood in a way that text cannot. No other industry has as rich a visual history - all created by (drum roll please) the still photographers.

Q. Do you photograph the entire crew?

A. Most attention is paid to the director, actors and producers. Following close behind would be department heads, who have a significant impact on the look of a film. Keep in mind that there are hundreds of people involved and many of them never come near the set. (Have you ever tried to read all of the credits at the end?) So it would be impossible to cover them all.

Q. How much do you let the approval process affect you? [Note: all photographs must go through a rigorous approval process by all actors and studio representatives]

A. Not at all. I do the best I can and have no emotional attachment to most of the work

Q. You don't get upset when you think you've done some great work and it doesn't get approved?

A. No, not at all

Q. Really? Is that because you've just become jaded over the years?

Q. Do you feel any sense of historical responsibility when working on films?

A. Yes, most definitely. Still photographers provide the historical visual record of Hollywood in a way that text cannot. No other industry has as rich a visual history - all created by (drum roll please) the still photographers.

Q. Do you photograph the entire crew?

A. Most attention is paid to the director, actors and producers. Following close behind would be department heads, who have a significant impact on the look of a film. Keep in mind that there are hundreds of people involved and many of them never come near the set. (Have you ever tried to read all of the credits at the end?) So it would be impossible to cover them all.

Q. How much do you let the approval process affect you? [Note: all photographs must go through a rigorous approval process by all actors and studio representatives]

A. Not at all. I do the best I can and have no emotional attachment to most of the work

Q. You don't get upset when you think you've done some great work and it doesn't get approved?

A. No, not at all

Q. Really? Is that because you've just become jaded over the years? A. Not jaded; just realistic. Many of my best photos have never seen the light of day and never will. Other, more pedestrian work, gets published on a regular basis.

The studio's needs are specific and pretty pictures that don't fill those needs are of little value. That should not affect the way you shoot. Sometimes those photos are used. Sometimes, they are not. I am not emotionally attached.

Q. Film shoots have notoriously long workdays. What was your longest?

A. There have been a number of films that went over 20 hours. A twelve-hour day is considered short. And now, with the elimination of a number of union rules protecting workers, twelve is often only the beginning. It is a dangerous trend that has resulted in deadly accidents. Everyone in the business has stories of having fallen asleep at the wheel while driving home. I fell asleep and drove though a concrete wall on San Vicente very early in the morning after a full week of insanely long days. Our director also ran off the road on the same day. So our hours were trimmed a bit. Others have not been as lucky and have been killed.

Q. Have you ever turned a movie down because you didn't like the screenplay? And if so, for what reason?

A. Yes. There have been a few that were just vulgar that were easy to say "no" to. In recent years I've turned down a number because they would have kept me away from home for too long.

Q. I have an important question (laughter). Do you have a movie you want to direct?

A. No. Maybe someday, if I ever feel that I have finally mastered my craft, I will give thought to directing or brain surgery, each of which I am equally unqualified. That has not happened yet.

Q. Are there any final thoughts that you would like to share with photographers who are considering getting into motion picture stills?

A. Not jaded; just realistic. Many of my best photos have never seen the light of day and never will. Other, more pedestrian work, gets published on a regular basis.

The studio's needs are specific and pretty pictures that don't fill those needs are of little value. That should not affect the way you shoot. Sometimes those photos are used. Sometimes, they are not. I am not emotionally attached.

Q. Film shoots have notoriously long workdays. What was your longest?

A. There have been a number of films that went over 20 hours. A twelve-hour day is considered short. And now, with the elimination of a number of union rules protecting workers, twelve is often only the beginning. It is a dangerous trend that has resulted in deadly accidents. Everyone in the business has stories of having fallen asleep at the wheel while driving home. I fell asleep and drove though a concrete wall on San Vicente very early in the morning after a full week of insanely long days. Our director also ran off the road on the same day. So our hours were trimmed a bit. Others have not been as lucky and have been killed.

Q. Have you ever turned a movie down because you didn't like the screenplay? And if so, for what reason?

A. Yes. There have been a few that were just vulgar that were easy to say "no" to. In recent years I've turned down a number because they would have kept me away from home for too long.

Q. I have an important question (laughter). Do you have a movie you want to direct?

A. No. Maybe someday, if I ever feel that I have finally mastered my craft, I will give thought to directing or brain surgery, each of which I am equally unqualified. That has not happened yet.

Q. Are there any final thoughts that you would like to share with photographers who are considering getting into motion picture stills? A. Yes. The Boy Scout motto says it best: "Be Prepared." Do not come to the party until you have some solid experience behind you, the necessary equipment and the knowledge. And if you have an ego, leave it at home. I could go on and on, but I'm sure there is a limit to your patience.

Oh and one more thing - and this is very important. If you want to get into motion picture stills so you can hang around Hollywood, rub elbows with the stars, stroll down red carpets and wear sunglasses, move on, there is nothing for you here.

Q. So lets completely switch gears here and talk about you personal work. Tell me a little bit about that. What have you been doing? What have you been photographing?

A. Like you, I seldom go out without a camera. Invariably, I regret it when I do.

Recently, I took a photo of a flower with the iPhone and I was surprised at the results. I had been using it to make visual notes, but never thought about it's potential as a "real" camera. The flower photo was good enough to make me wonder what I could do with it, so I gave myself two weeks to shoot only with the iPhone, which meant no control over the exposure, no lens choices, no control of any sort, except for framing the image. To maintain the purist approach, I also restricted myself; no cropping or image manipulation other than contrast and sharpening in Photoshop.

I was both stunned and thrilled with the results. I'm now putting together a book and Ray Bradbury has written an introduction. The iPhone is not going to replace cameras for work, but it offers some very interesting possibilities that I look forward to exploring further.

Now if you are finished, I have a question for you:

Yes?

Are we going to have a glass of wine now? It must be cocktail hour somewhere on the planet and all this talk makes me thirsty.

A. Yes. The Boy Scout motto says it best: "Be Prepared." Do not come to the party until you have some solid experience behind you, the necessary equipment and the knowledge. And if you have an ego, leave it at home. I could go on and on, but I'm sure there is a limit to your patience.

Oh and one more thing - and this is very important. If you want to get into motion picture stills so you can hang around Hollywood, rub elbows with the stars, stroll down red carpets and wear sunglasses, move on, there is nothing for you here.

Q. So lets completely switch gears here and talk about you personal work. Tell me a little bit about that. What have you been doing? What have you been photographing?

A. Like you, I seldom go out without a camera. Invariably, I regret it when I do.

Recently, I took a photo of a flower with the iPhone and I was surprised at the results. I had been using it to make visual notes, but never thought about it's potential as a "real" camera. The flower photo was good enough to make me wonder what I could do with it, so I gave myself two weeks to shoot only with the iPhone, which meant no control over the exposure, no lens choices, no control of any sort, except for framing the image. To maintain the purist approach, I also restricted myself; no cropping or image manipulation other than contrast and sharpening in Photoshop.

I was both stunned and thrilled with the results. I'm now putting together a book and Ray Bradbury has written an introduction. The iPhone is not going to replace cameras for work, but it offers some very interesting possibilities that I look forward to exploring further.

Now if you are finished, I have a question for you:

Yes?

Are we going to have a glass of wine now? It must be cocktail hour somewhere on the planet and all this talk makes me thirsty.