Nude Descending A Staircase by Marcel Duchamp was a cubist-inspired painting and was the kind of art that suggested to photographers that there was no point trying to emulate painting styles of the past that modern painters had themselves evolved beyond. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo

“Modern art” really began in Europe in the late 19th century. Painters that are now icons of impressionism like Monet, Manet, Renoir, Picabia and Pizarro were followed by legends including Picasso, Matisse and Van Gough (and many sculptors as well) broke from the traditions of the past and revolutionized what was accepted as fine art.

It is interesting, and not really coincidental, that all of these happened just after the technology and practice of photography came into being and photographs became a major vehicle for creating images of the people, places and the world in general – a task that had been left to artists for thousands of years until then.

Photography displaced many of the primary reasons for the making of paintings. So it was inevitable that painters would look for new purposes when it came to creating painted images.

Henri Matisse was one of the masters of modern art. He was more an expressionist artist and was more interested in his reaction to reality than to reproducing reality itself. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo A pictorialist-style photo of painter Henri Matisse by Edward Steichen. In a few years, Steichen would evolve away from pictorialism to shoot a documentary, commercial and fashion images and become one of the major photographers of the 20th century. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo

But while photography was quickly adopted by the public as a way of capturing images of themselves, their friends and family and their lives – especially after the introduction of the the

Kodak Brownie and the ability to easily shoot snapshots – photographers whose intentions were to create

fine art most often used a style known as

“pictorialism” – a style in which the photographer has somehow manipulated what would otherwise be a straightforward photograph, often using soft focus, as a means of “creating” an image more “artsy” looking, rather than simply recording what was in front of the camera lens.

This type of photography tended to demonstrate the insecurity of those trying to get the medium of photography taken seriously than just being viewed as a means of mechanical reproduction. As the technology developed, using a camera allowed almost anyone to shoot relatively sharp, detailed images of the world around them. So photographers with more artistic aspirations decided that photography would be taken as seriously as painting if the images being produced

looked more like paintings.

Pablo Picasso, inventor of Cubism along with George Braque, remained one the most innovative and successful artists throughout his career. A master draftsman, Picasso could make a cow look like a cow if he wanted to. But was more interested in expressing his inner vision what the world looked like. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo American artists like John Whorf were also part of the 1913 Armory show. Their work generally showed less influence of movements like expressionism and impressionism, but this style is a long way from a highly detailed historic painting by David. It is also notable for choosing an everyday scene for a subject rather than something classical, grand and glamorous. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo

However, while the development of what we now call modern art was rapidly evolving in Europe, it was virtually unknown in the United States. There were American artists who were fully aware of what was going on across the Atlantic – in fact, many American painters made regular trips to places like Paris – but the more modern work they were producing got very little attention in the United States.

Then came the 1913 Armory Show. From Wikipedia:

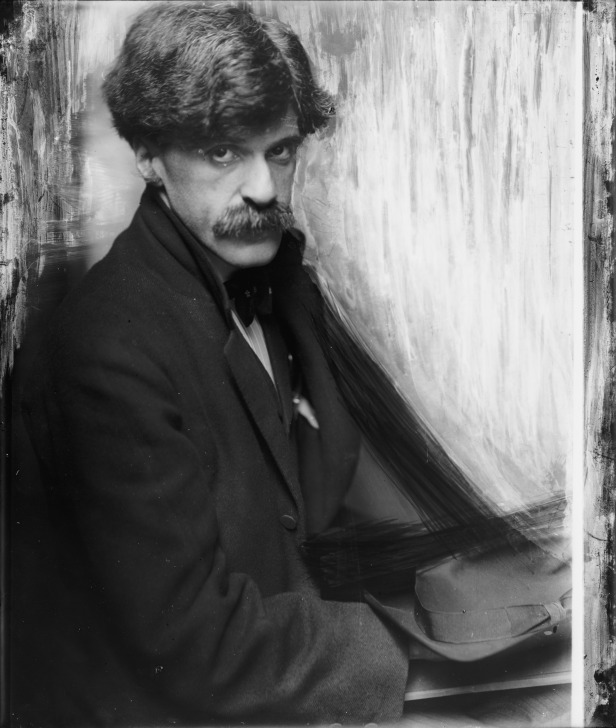

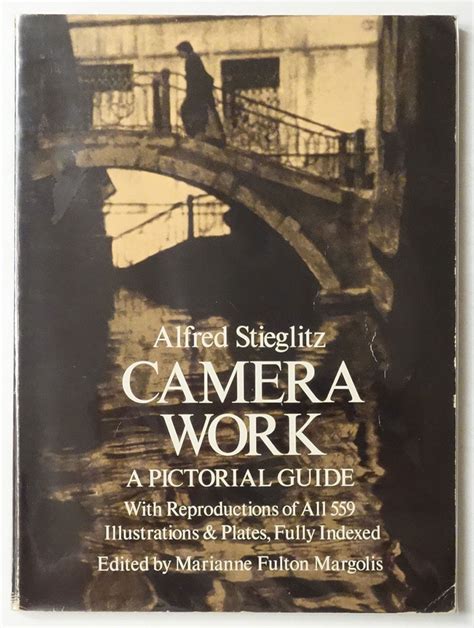

The Armory Show , also known as the International Exhibition of Modern Art, was a show organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors in 1913. It was the first large exhibition of modern art in America, as well as one of the many exhibitions that have been held in the vast spaces of U.S. National Guard armories.Alfred Stieglitz was a photographer and one of the most influential promoters of both photography and modern art. He tried unsuccessfully to sell modern paintings, mostly from Europe, in the 1920s that would be worth millions soon after. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo A pictorialist railroad image by Alfred Stieglitz. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo The magazine Camera Work was a major supporter of developing photographers like Paul Strand and Edward Steichen. Over time its pages were increasingly full of very sharp, realistic photos documenting reality without the use of artsy pictorialistic styles. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo The three-city exhibition started in New York City’s 69th Regiment Armory, on Lexington Avenue between 25th and 26th Streets, from February 17 until March 15, 1913.

The show became an important event in the history of American art, introducing astonished Americans, who were accustomed to realistic art, to the experimental styles of the European avant-garde, including Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism. The show served as a catalyst for American artists, who became more independent and created their own “artistic language.”

Edward Steichen was mentored by Alfred Stieglitz and became one of the most important photographers of the 20th century. Staring in the era of pictorialism, Steichen becomes an advertising and fashion photographer and in World War II shot war photos as an officer in the US Navy. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo Edward Steichen published a number of books of his work, most of which are still available on Amazon and other services. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo Edward Steichen went a long way from soft focus pictorials to photographing the Pacific war from the deck of an aircraft carrier as a naval officer. Photo credit: Edward Steichen for the US Navy. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo

The most important supporter of photography as art in the United States was Alfred Stiegliz, who had himself been doing pictorials photography. He had a small gallery in New York City where he most exhibited the work of photographers but after the Armory Show, he also showed a few paintings by artists like Picasso and Matisse. But although these works were available for very modest sums, and would eventually be worth millions, there was little interest in purchasing them at the time.

But the effect of these works of modern art on photography was substantial.

What was the point of trying to create photos that emulated traditional paintings when modern painters themselves were no longer working in this tradition? But since these artists had to a large degree (but certainly not entirely) abandoned the effort to make paintings as realistic as possible, this obviously left photography free to do what is does best – capture images that show people and the real world as they really look.

In the early 20th century there were certainly realistic, documentary photographers like Jacob Riis, who documented slum living the plight of immigrants. But photographers like this were not intending what they created to be viewed as fine art – even if much of this work eventually made its way to art galleries and the art market. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo

Stieglitz championed such photographers as Edward Steichen and Paul Strand, both of whom created photos that were direct, clear-cut and detailed – although by choosing the right light, angle, cropping, and composition they continued to exercise a great degree of artistic control. And while there continued to be photographers with a pictorialist approach, and some still work with the way today, the predominant approach to shoot photos became creating clear, sharp and realistic-looking images.

This vintage landscape photo shows the soft focus, artsy approach that was typical of this style. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo Ansel Adams is practically the epitome of the sharp focus, detailed and great depth of field style of photography. His methods were night and day different from the approach used by pictorialist photographers. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo

In the 1930s

Henri Cartier-Bresson took his Leica to the streets and created “decisive moments.” Ansel Adams and Edward Weston captured dramatic landscape photos. Life Magazine brought documentary photos shot all over the world to its readers. Robert Capa used his camera to take us to the beaches of D-Day.

W. Eugene Smith took the documentary photo series to new levels. Sebastião Salgado traveled the world documenting the poor and powerless, as well as the grandeur of nature, in analog black-and-white photographs that are both highly formal and unflinchingly documentary.

The introduction of digital photography has created another sea change in the world of photography. Painter David Hockney, who also works with photography, has said that the new technology has given photographers control over their images that only painters have had in the past. Nowadays we have everything from super-realistic, documentary photography to very abstract images created with the help of software like Photoshop. Anything and everything is possible in photography today.

There could be an element of abstraction in photos like the “decisive moment” images shot by Henri Cartier-Bresson. But they were mostly about using the camera to observe and capture fleeing moments in time that can’t be done by anything but a camera. Credit: Henri Cartier-Bresson | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo Few photographers have ever pursued documenting a subject with the focus and tenacity of W. Eugene Smith . Ironically, many vintage journalistic photos have become best sellers in the fine art photo market. ©W. Eugene Smith – Black Star | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo “Dog’s Best Friend.” An artist can walk around with a sketch book, but it takes a camera to record a moment of time in a specific place like this. The resulting photo might be journalistic, documentary, artistic – all all of the above. Credit: Bill Dobbins. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo

But modern photography really started when photographers were confronted by the world of modern art and realized they would need to find a kind of photography that represented the real nature and strength of this new medium. And the watershed event that helped make this happen was the 1913 Armory Show in New York City.

Before photography, there was no way to capture and study phenomena like a bird in flight or the breaking of ocean waves. It took a genius artist like Leonardo da Vinci, with an incredible eye, to come even close. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo

Ironically, although photographers at one point abandoned shooting photos consciously intended to be “fine art” in favor of a more realistic and documentary style, many of these photos are now work a great deal of money in the

fine art photo market . Quite often, what is defined as art is not a matter that is decided by the artists.

**********************************

Bill Dobbins is a veteran photographer and videographer located in Los Angeles who has exhibited his fine art images in two museums and a number of galleries and has published eight print and 16 eBooks, including two fine art photo books:

WEBSITES

A traditional, realistic painting by Jacques-Louis David. This type of detailed historic painting was popular at the beginning of the 19th century. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo As the 19th century progressed, a painting by J.M.W. Turner shows the growing trend to a more abstract approach to art. This Turner show both expressionism – how he felt about the subject – and impressionism – how light seems to be the most important subject he is trying to capture. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo The Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh was one of the paintings that inspired the next generation of painters who would become the founding artists of what we came to call modern art. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo Impressionism, expressionism, surrealism and all the other “isms” eventually lead to increasing reliance on abstraction, as in this work by Kandinsky. While a few photographers also attempted to shoot abstract images, realistic photography became the predominant style of the 20th century. | Source: https://bit.ly/2MCCavo